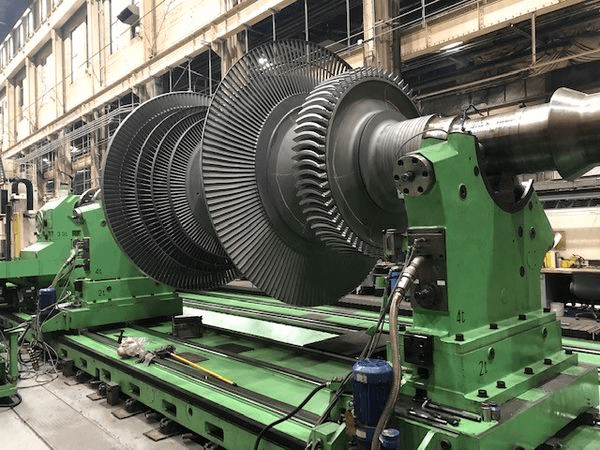

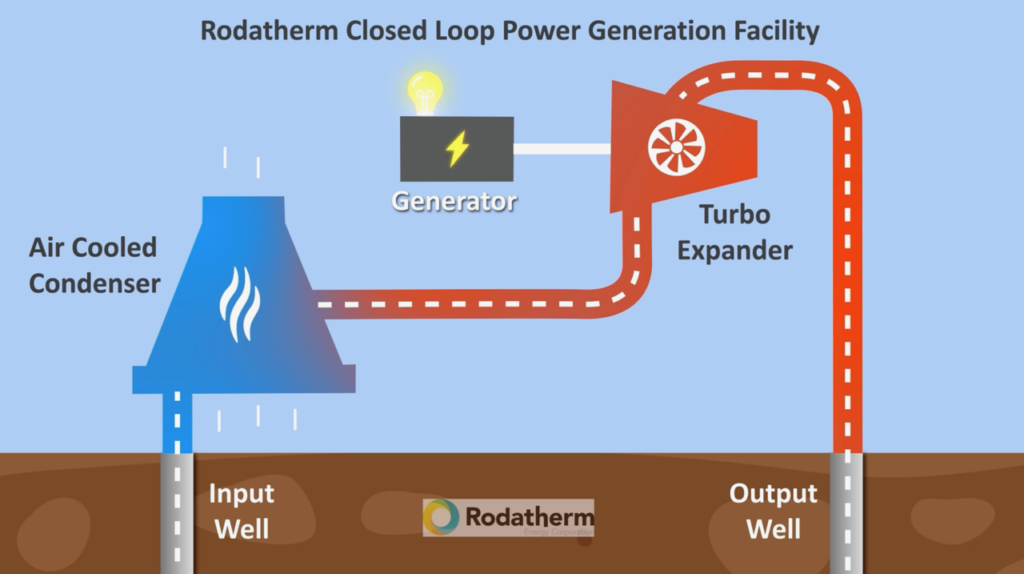

Federal regulation of customer loads located next to existing power generating facilities, referred to as “co-located loads,” have become a significant area of interest for the electric industry. Large industrial loads have taken an interest in this configuration because it promises a faster, streamlined pathway to interconnecting to the grid and meeting their power supply needs.

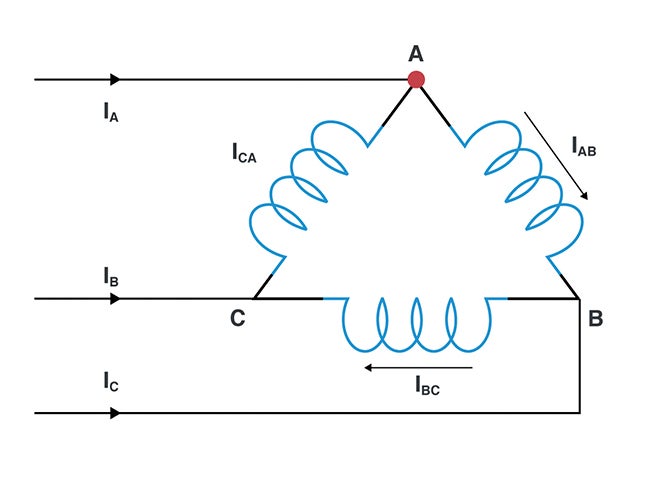

Data centers, in particular, operate 24/7 and require reliable and continuous sources of electricity, but many other large loads including, for example, electrolyzer facilities (which are used in the production of green hydrogen) are exploring co-location. While the exact electrical configuration may vary, under one popular approach, the data center load is served fully and exclusively by the co-located generator pursuant to a long-term power purchase agreement. This particular type of arrangement has led to disputes between developers and traditional regulated utilities on difficult issues including grid reliability and cost allocation.

COMMENTARY

As these issues continue to play out across multiple forums and proceedings, interested parties are looking for some measure of certainty that their desired business arrangements will pass regulatory muster and provide a cost-efficient, reliable source of power.

Based on the recent growth in data center loads nationwide, interest in co-location options is likely to increase. Currently, only 15 states account for 80% of the national data center load. But with data center growth forecast to exceed $150 billion through 2028, a concrete and unified regulatory regime for co-located loads is becoming increasingly important.

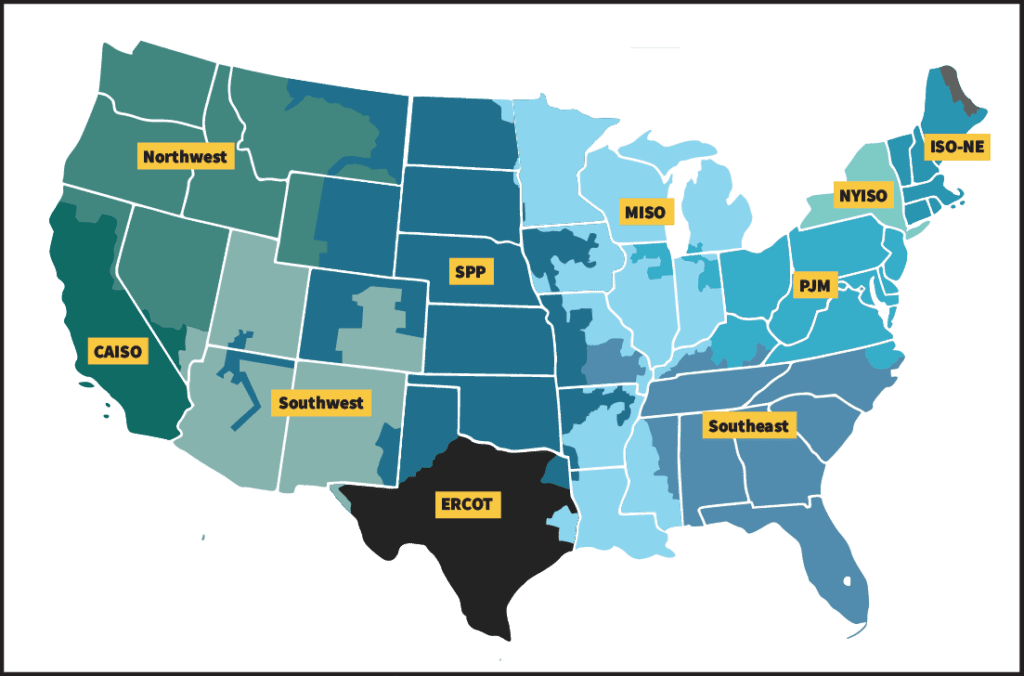

How have regulators treated co-located load arrangements from a legal/regulatory perspective? On Nov. 1, 2024, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) addressed the issue of co-location of large loads at existing generating facilities in two separate dockets. First, in Docket No. AD24-11, FERC convened a technical conference addressing many of the issues raised by this type of business arrangement. Second, in Docket No. ER24-2172, FERC issued an order rejecting an amended interconnection service agreement (ISA) in the PJM region that sought to facilitate one such co-location arrangement. In both proceedings, FERC addressed concerns and issues involving co-located loads with respect to reliability, cost allocation, and national security. Both of these regulatory developments are discussed below.

Commissioner-Led Technical Conference Addressing Key Issues

At the technical conference, certain commissioners had differing opinions on FERC’s role with respect to co-located loads. Chairman Phillips expressed his concern about national security and the need to promote and preserve the U.S. competitive advantage in the artificial intelligence (AI) industry, taking the position that facilitating the interconnection of large loads through co-location is a matter of national security and is thus one of FERC’s chief responsibilities. At the other end of the spectrum, Commissioner Christie displayed a more cautious approach to co-located loads because of the potential impacts on reliability (chiefly in the form of resource adequacy) and concerns of fair allocation of costs and the possibility that this arrangement will avoid non-bypass-able charges that all retail loads must pay.

Some of the key takeaways from the technical conference:

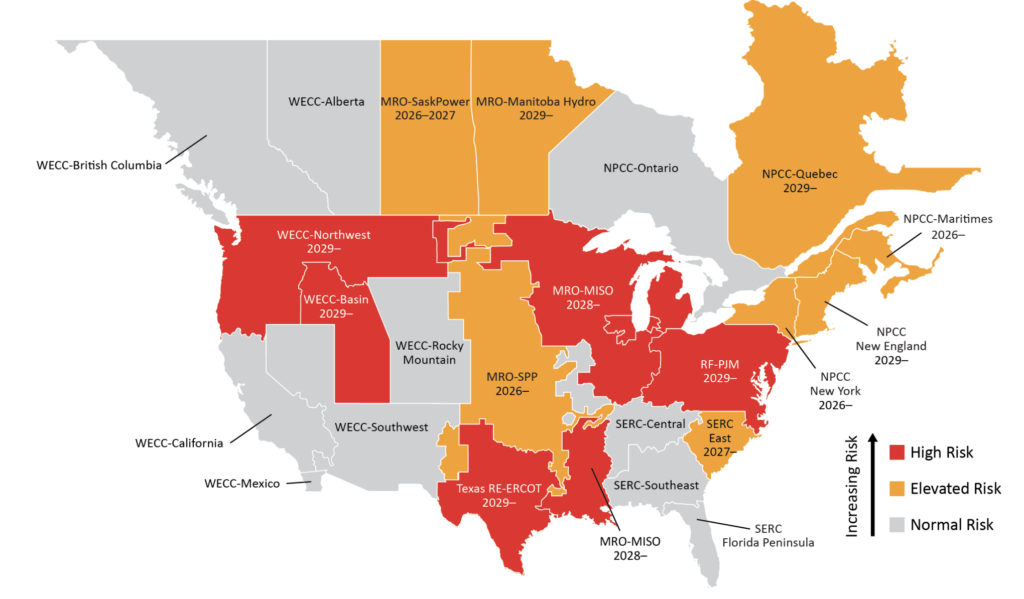

How to frame the resource adequacy issue: Opponents to the co-located load structure argued that taking some or all of the capacity from an existing generator and dedicating it to serve a behind-the-meter co-located load will decrease the grid’s capacity, hindering reliability. Proponents argue that these loads will require capacity whether they are located in front of the meter or behind the meter.

There is a diminished resource adequacy that is not a concern if the co-located load brings its own generation (i.e., interconnects alongside new generation that is developed specifically to serve that load, whether in whole or in part). But that concept comes with additional issues, for example, if the generation must enter the interconnection queue, which would create delays.

Panelists disagreed as to whether lessons learned from combined heat and power loads could be used in the context of data center load growth or whether new load models needed to accurately forecast the growth.

Every panelist agreed that large loads must pay their fair share of costs, but they disagreed on what those costs entail. Opponents argue co-located loads are not isolated from the grid and should bear some level of transmission charges because they use ancillary services, such as black start, and benefit overall from being connected to the grid, which can be accessed for alternative power supply when the on-site generation fails to operate. Proponents argue that system protection schemes can in fact fully isolate loads, and to the extent that such loads (or, more precisely, the generators themselves) use ancillary services from the grid, the value of those services can be quantified (but is probably a de minimis amount).

FERC is seeking comments on the issues discussed during the technical conference, which are due on Dec. 9, 2024. Those comments will help develop a record for FERC to potentially take some action—whether that be a policy document, a notice of proposed rulemaking, or a decision to address these issues on a case-by-case basis. Any parties interested in these issues should consider contacting their energy regulatory counsel with any questions or for assistance submitting comments in the docket.

A Setback, But Not the Last Word

FERC’s November order rejected PJM Interconnection’s (PJM’s) proposed amendment to the Susquehanna ISA, dealing a significant blow to data center developers seeking to use existing interconnections to speedily connect their projects to the grid. In a split 2-1 decision, FERC rejected PJM’s proposed nonconforming provisions in the Susquehanna ISA that would have allowed the generator to modify its interconnection facilities to interconnect a large load and fully serve it from the generator, without using power from the transmission system or designating the load as a Network Load (a so-called Fully Isolated Co-Located Load). The majority consisted of Commissioners Christie and See, with Chairman Phillips filing a separate dissent and Commissioners Rosner and Chang abstaining.

The majority found that PJM failed to meet the “high burden” placed on non-conforming provisions to a transmission provider’s pro forma agreement on file at FERC. Under that standard, “non-conforming agreements may be necessary for interconnections with specific reliability concerns, novel legal issues, or other unique factors.” In other words, the issues that warrant deviation from the pro forma agreement must be specific and unique to that particular interconnection. But the majority found that the Susquehanna ISA did not meet that standard because it relied heavily on the “PJM Guidance on Co-Located Load” document issued in March 2024, which FERC found was intended to be generally applicable to all similarly situated interconnection customers and thus was not unique to that specific interconnection.

In a separate concurrence, Commissioner Christie, who led the majority in the FERC order, asserted that he is keeping an “open mind” on co-location, but the facts of this particular proceeding were insufficient for PJM to meet its burden of proof. Commissioner Christie further stated that a similar co-location arrangement may be permissible under the Federal Power Act, but the one proposed here did not pass muster. For Commissioner Christie, the key issues that need to be addressed are grid reliability and consumer costs, which may be further addressed following the November technical conference.

Chairman Phillips’ dissent argued that this proceeding “represents a ‘first of its kind’ co-located load configuration” that warranted approval by FERC as proposed. By accepting the ISA and directing PJM to submit regular informational filings that track certain issues under dispute, PJM could have then worked through its stakeholder process to develop a generally applicable policy addressing co-located load issues.

Chairman Phillips emphasized national security, as he did during the technical conference, which he believes is compromised if FERC creates “roadblocks” to the interconnection of data center loads needed to promote growth of the AI industry in the U.S.

Next Steps

How can interested parties engage in the ongoing discussion impacting co-located load arrangements? These issues are still being played out across the country, affording various opportunities to become involved, including before FERC in the PJM region and before state commissions, such as the Maryland Public Service Commission. With a stronger record and new commissioners who have had more time to learn about these issues, it is very possible that FERC policy will coalesce in the coming months in a way that provides greater regulatory certainty for developers pursuing co-located load arrangements.

Either way, as FERC grapples with these issues, industry participants who have relied on, or are interested in, self-generation options should monitor further developments closely, to ensure their interests in self-generation options in the future are not impaired or prevented. Energy regulatory counsel should be consulted for assistance with participating in FERC’s processes and monitoring developments and co-located loads. By remaining active in these proceedings, developers will be advantageously positioned to comply with future FERC precedent and account for the anticipated load growth of co-located resources.

—William D. DeGrandis is a partner, Gregory D. Jones is of counsel, and Alexander S. Kaplen is an associate in the Corporate Department at the Paul Hastings law firm.