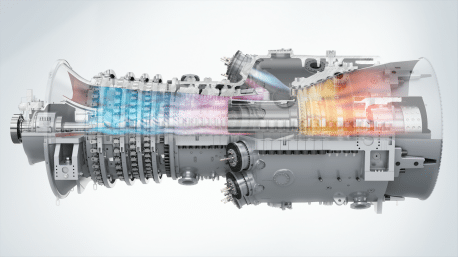

The gas turbine industry is facing its most significant supply chain challenge in decades, with backlogs extending years into the future and utilities scrambling to secure dispatchable capacity. To better understand the scope of the problem and what options utilities have, POWER spoke with John Shingledecker, principal technical executive with EPRI, and Bobby Noble, senior program manager for Gas Turbine Research and Development (R&D) with EPRI and an American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Fellow.

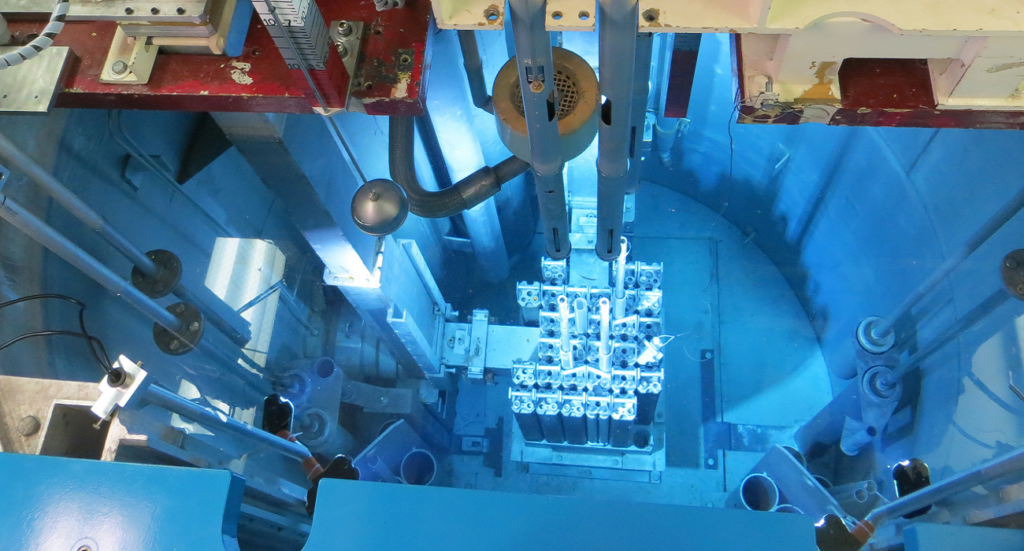

According to the EPRI experts, rotor forgings and hot-section blades have emerged as the primary bottlenecks, constrained by limited suppliers and highly technical manufacturing processes. The situation has grown severe enough that some large frame turbines have been shipped without rotors or blades, with installation occurring later onsite to maintain construction schedules. Delays in new hot-section blade deliveries have also driven increased emphasis on component re-use, re-manufacturing, and repair programs, they said.

Vendor Qualification Challenges

Qualifying new vendors offers no quick fix, the researchers explained. The timeline for bringing a new supplier online is highly dependent on the original equipment manufacturer (OEM), supplier, and specific component involved. Large forgings present particular challenges, the researchers noted, because only a limited number of suppliers exist globally, many of whom already serve multiple OEMs. Adding a new supplier may not significantly ease constraints if they are already engaged across the industry.

For advanced machines requiring single-crystal blades or exotic materials, the qualification process becomes even more complex, the EPRI experts noted. While raw material availability is generally not the issue, materials costs are driving up prices. Competition for nickel superalloys and cobalt has intensified, particularly with the rise of lithium-ion batteries. Aerospace and energy were once the primary users of cobalt, but battery demand now exerts strong influence on pricing, they said.

A Different Demand Driver

Unlike the gas turbine boom of the late 2000s, which was driven primarily by low gas prices, today’s demand stems from multiple converging factors, according to Shingledecker and Noble. These include near-term needs from data centers, limited dispatchable power options due to increasing non-dispatchable resources on the grid, and long-term electricity growth from electrification. New coal generation is no longer a viable option for most utilities, and natural gas supplies are more abundant than previously thought during the first boom, providing added stability for gas-fired generation investment.

Data centers are driving particularly acute short-term demand for dispatchable power, the EPRI researchers said. While they are not typically competing for large-frame turbines, they do compete directly with utilities for small- and mid-sized turbines in the 30 MW to 100 MW range—prime peaker territory. This competition has opened opportunities for new market entrants.

Near-Term Options for Utilities

For utilities needing capacity by 2028 but facing backlogs extending to 2030, options remain limited but available. According to the EPRI experts, many utilities are extending the life of existing thermal assets, pursuing repowering projects, and implementing turbine uprates through technologies such as inlet fogging and advanced modifications. EPRI, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory, is exploring uprate scenarios with potential double-digit percentage increases in output, they said. Meanwhile, renewables paired with battery storage continue to be part of the capacity mix.

The capacity pressure is accelerating adoption of smaller, modular solutions, the researchers noted. Orders for turbines under 20 MW reached record highs in 2025, and reciprocating internal combustion engine (RICE)-based power plants are also gaining traction. Aeroderivative units offer flexibility and rapid deployment, though they face similar backlog pressures due to competition with the commercial aviation industry for components and manufacturing capacity.

Quality and Market Dynamics

When supply chains are stretched, quality problems sometimes emerge. Often, however, this only becomes evident after components enter service, making them difficult to trace, the EPRI experts explained. EPRI’s research, including process compensated resonance testing (PCRT), has proven instrumental in detecting quality issues early. Past differences between vendors have been identified through serial number structures, they said.

The competitive landscape is also evolving. While GE Vernova, Mitsubishi Power, and Siemens Energy remain dominant, some reshuffling is expected, according to Shingledecker and Noble. Doosan Enerbility recently entered the North American market, signaling new competition. However, with the overall market expanding due to growing demand, market share shifts may be less significant than the overall growth in opportunity.

Long-Term Implications

Predicting how long the backlog will persist remains difficult, the researchers acknowledged. Expanding factory capacity and onboarding new vendors is a long-term process, not a quick fix. The prolonged turbine unavailability could alter the generation mix for 2030 and beyond.

Supply chain challenges, combined with long-term demand growth, are driving renewed interest in advanced nuclear and long-duration energy storage, the EPRI experts noted. Utilities increasingly recognize the need for diverse generation portfolios to manage risks related to supply chains, fuel costs, and system flexibility, they said. The turbine bottleneck, while painful in the near term, may ultimately accelerate the transition toward a more diversified and resilient power generation fleet.

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor.