How companies respond to the COVID-19 pandemic will determine their public reputations, and those of their leaders and key employees, for years if not decades.

This, along with public safety, is why “Priority Number One” for the CEOs of power producers, utilities, and grid operators is to make sure critical employees, such as control room operators, are healthy and to sequester them until the pandemic has subsided.

This is a tough, but necessary ask.

It is tough on the women and men who will be away from their families for weeks at a time. It strains the power industry financially, especially at a time when demand and prices are falling. And, frankly, it is also difficult because few governors, utility commissioners or other emergency planners seem to understand the danger as they have not been proactively calling for this step.

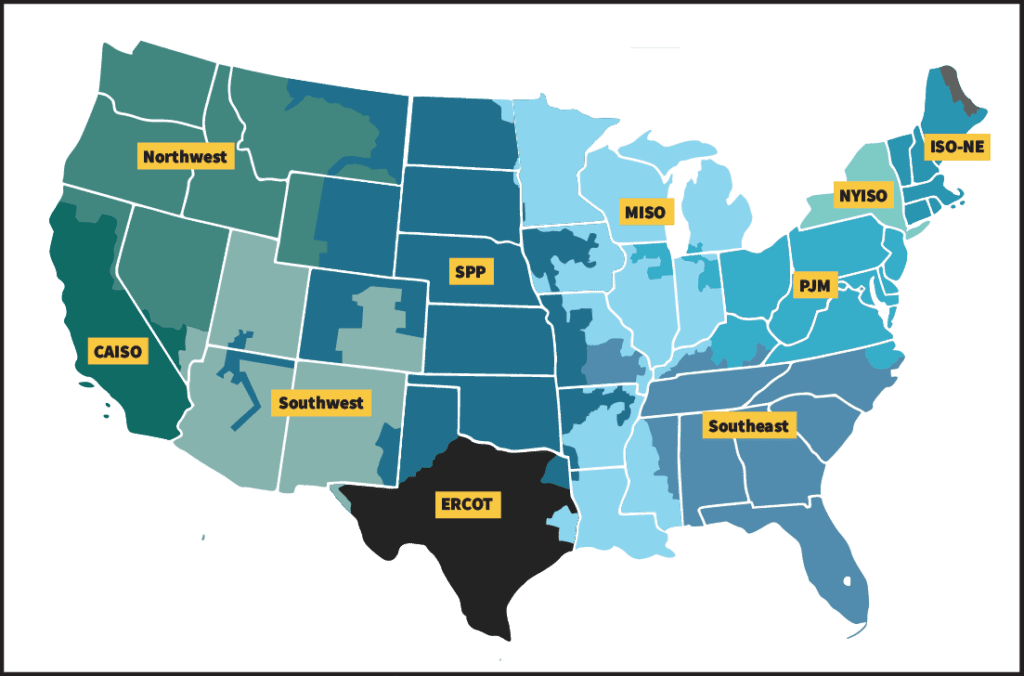

But many of the best and brightest in the power industry do understand this and have already implemented sequestration. This includes hundreds of workers with the New York Independent System Operator, National Grid, the New York Power Authority, PJM Interconnection, and others.

The thorough pandemic preparations of the industry notwithstanding, it is a question of when and not if a large group of workers at power plants, system operators and/or utilities will be infected. This has already happened at the New York Stock Exchange, among air traffic controllers and in the food industry.

Just last week, with the announcement that one major meat plant is closing due to infected employees, there is now concern about the U.S. meat supply. The effects at an ISO, utility, or power producer having to close from a group of infected employees could be much more severe.

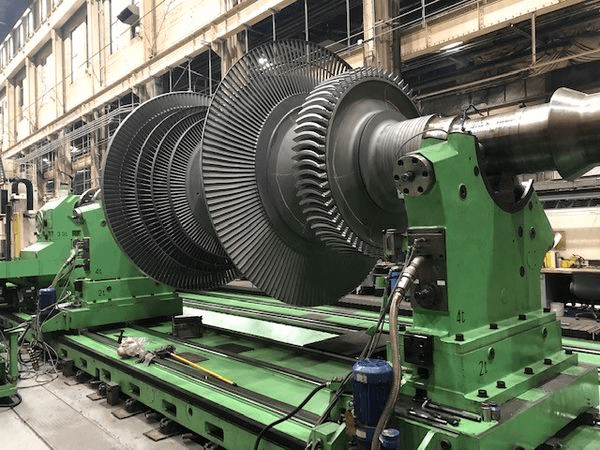

That is because a few dozen employees are often critical for keeping the power on for hundreds of thousands, or even millions of people. Losing power means economic and social and disruption at a time of great public stress and when we can least afford it.

The industry should call on governors to make testing of critical power industry workers, who must work near each other, a priority and relentlessly demand such tests. Having these workers infected with COVID-19 must be avoided as it presents a Hobbesian choice: risk workers’ lives or shut down the facility and put the public in danger.

The absence of electricity would not only disrupt remote work and school activities, it would create a health emergency of its own. Senior citizens, already most impacted by COVID-19 would be most vulnerable to a power outage. Those on electrically powered medical devices at home would face a choice: risk not using the equipment or risk going to an emergency room at a crowded and likely stressed hospital.

Initially, all such folks who are sequestered should be volunteers—and they should be paid quite well. Many folks in the electricity industry have a service attitude and are used to working long, unselfish hours in a crisis. Many of those now sequestered in the power industry in the U.S. have volunteered.

Cost is no doubt a concern, but it should not be a barrier. Utilities, power generators and independent system operators should be reimbursed for the compensation and other costs of housing key professionals onsite.

Utilities should seek reimbursement from regulators for these costs, but they should take the actions promptly and regardless of whether reimbursements are likely or not. Federal funds should be included in a future stimulus package for such assistance.

In this environment, it is also important that utilities double down on cyberattack prevention. Foreign adversaries and other hackers’ intent on being able to compromise the U.S. electric grid will no doubt be using this time of stress to accelerate these efforts to steal data and be able to disrupt the grid.

The power industry has come to a critical juncture. It can either be at the forefront of ensuring public safety by rapidly expanding the number of key workers who are being sequestered or it can roll the dice on public safety and its own reputation.

—Paul Steidler is a senior fellow with the Lexington Institute, a public policy thank tank based in Arlington, Virginia.