It’s often said that technology runs well ahead of the law. Not so long ago, the process of setting electric utility rates was only slightly more dramatic than watching paint dry. This was by design. There was generally only one goal—keeping the lights on—and everything else was structured to support it. The utility generated the electricity, and the customers used it. The utility projected what it would need to support future reliability, the utilities commission approved what it thought prudent, and the utility was rewarded with a return that was intended to ensure its future financial health.

Many things have changed since the decades when the regulated monopoly model held sway over all, but until very recently, reliability remained the major consideration in designing electric rate structures. Those days, however, may be coming to an end.

Into the Trenches

Over the past year or so, previously cerebral disagreements over how to handle customers who self-generate—particularly with residential rooftop solar—have exploded into partisan warfare. As just one sign of how charged emotions around this issue have become, in February, in the midst of a contentious debate over changes to Nevada’s net-metering system, things became so heated that officials barred several pro-solar protesters from a meeting of the Nevada Public Utilities Commission (PUC) because they were openly carrying firearms (something that’s legal in public buildings under Nevada law).

Everyone seems to agree that the traditional model does not work well, if at all, when a substantial portion of retail customers are putting electricity back onto the grid or are consuming it in ways that run counter to traditional assumptions. Nearly everyone agrees that things need to change, but there, unfortunately, the agreements end.

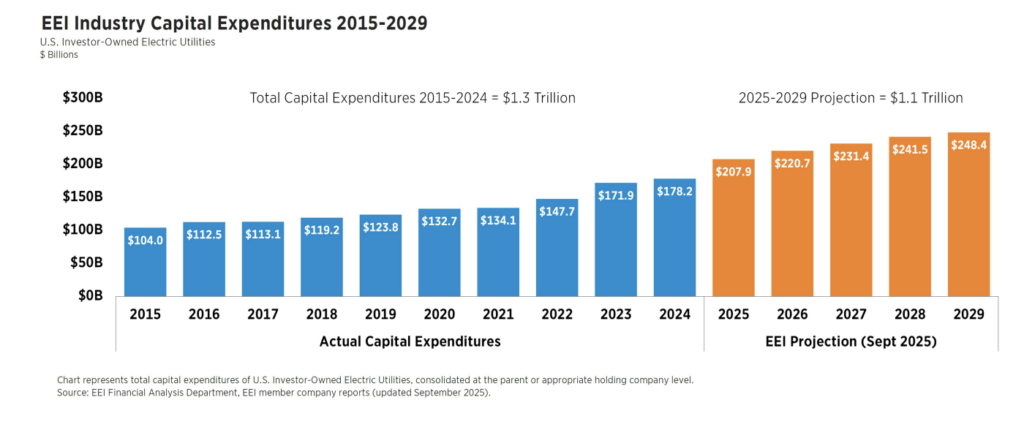

Much of the competing positions are staked out in two documents released in 2016, one from the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) and the other from the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA). The EEI paper, “A Primer on Rate Design for Residential Distributed Generation”, argues that the problems stem primarily from traditional rate structures, in which the lion’s share of a bill is based on electricity consumed while only a small portion covers a utility’s fixed costs. That’s a problem, the EEI says, because most of the cost of generating and delivering that electricity is fixed and sunk in the power plants and transmission and distribution infrastructure. Customers who reduce their bills by self-generating are shifting those costs onto customers who don’t.

The SEIA paper, “Rate Design for a Distributed Grid”, published a few months later, argues that this approach is far too narrow. The EEI approach counts as “fixed” certain costs (such as fuel and labor) that are in fact dynamic, and it fails to account for benefits to the grid (such as reduced peak demand and deferred transmission costs) that distributed generation (DG) offers. In addition, it doesn’t consider larger societal benefits, such as reduced pollution and climate change mitigation.

Valuing the costs and benefits of DG is the core disagreement. The EEI paper sees it as a net cost, and one that unfairly shifts those costs to non-DG customers. The SEIA paper sees it as a net benefit, both to society and to ratepayers as a whole. The SEIA dismisses concerns about the uncertainty DG creates for utilities, while the EEI dismisses the “larger benefits” argument as something that will “distort ratemaking decisions” because those benefits are “difficult to quantify.” And so on.

Incoming Fire

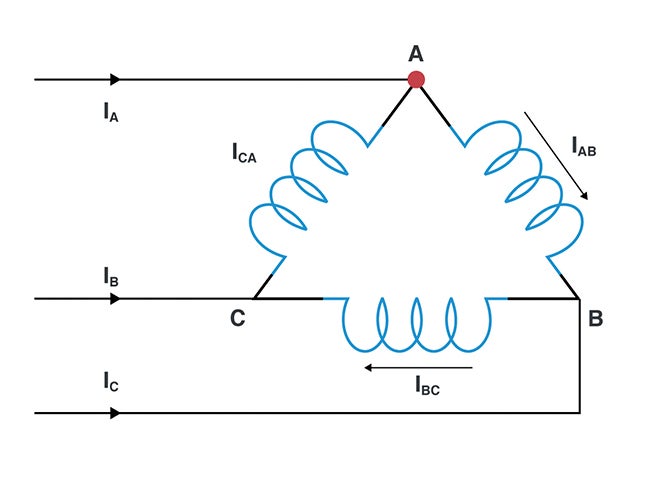

The arguments thus far have focused mainly on solar, but more problems are on the way as residential storage becomes more economic and smart grid technology goes mainstream. One of the criticisms of DG in the EEI paper is that many customers sell power back to the grid at full retail price regardless of the instantaneous wholesale price. But technology is already on the market (albeit priced for commercial customers) that allows real-time balancing of customer DG and storage based on the price of power, allowing customers to “buy low and sell high.”

It doesn’t take a PhD in mathematics to see how critical rate design is to the future grid. The rooftop solar market in Nevada collapsed after the state changed its net-metering system. Technology that allows a utility to defer infrastructure investments is a bad thing from its perspective if the rate structure is designed to compensate it for those investments. Every kilowatt of rooftop solar is lost profit for the utility.

And it’s a problem for more than just customer bills and company profits. Advances in energy storage, smart inverters, and similar technologies offer the potential for dramatic improvements in energy efficiency (EE) and the carbon intensity of the grid, but too often these technologies are running into rate structures (and regulators) that seem to view such changes as a threat.

One hopeful sign is that some utilities and EE advocates are working to find common ground. In early November, the Rate Design Initiative, organized by the Alliance to Save Energy, completed its first round of discussions. The initiative includes major generators and utilities such as Exelon, National Grid, Pacific Gas & Electric, and Southern Co., as well as firms working in the EE space. Much work remains to be done, but the group has agreed on some core principles for rate design and will be adding additional members next year. It’s a small start perhaps, but one that is sorely needed. ■

—Thomas W. Overton, JD is a POWER associate editor.