Doosan Heavy Industries & Construction (DHIC) this summer made major strides to establish itself at the core of South Korea’s strategy to become only the fifth country to own an independent gas turbine model.

Following announcements of a deal in December 2019, the Changwon, South Gyeongsang–based company on June 22 cemented dual contracts valued at a total $300 million with Korea Western Power Co. (KOWEPO) for the construction of the 500-MW Gimpo Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plant, which is located in Gimpo’s Yangchon-eup in the Gyeonggi Province. That project, which is scheduled to go online in the first half of 2023, will use liquefied natural gas (LNG) to produce district heat and power to nearby regions. But it is also notable because it will demonstrate South Korea’s first locally manufactured large gas turbine.

Just weeks later, on July 13, DHIC inked a memorandum of understanding to cooperate with KOWEPO, a company that generates about 10% of South Korea’s power, to jointly develop a national standard for a combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) power plant model that can compete in the cutthroat global gas turbine market. The two companies also agreed to jointly promote the growth of South Korea’s fledgling gas turbine sector by supporting small and medium enterprises and mid-sized companies, which they envision will form the basis of the nation’s technology supply chain.

Going Heavy on LNG

The developments are notable steps in South Korea’s strategy to develop a homegrown gas turbine industry, and if it succeeds, the country will join the U.S., Germany, Japan, and Italy, where the world’s biggest gas turbine original equipment manufacturers (OEMs)—General Electric, Siemens Energy, Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems (MHPS), and Ansaldo Energia—are headquartered.

While South Korea’s efforts stem from a national project initiated in 2013 by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE), and the Korea Institute of Energy Technology, to curb the country’s dependence on foreign imports, its recent pivot toward renewables and away from nuclear and coal power has boosted the national project’s importance.

In its draft 9th basic energy policy released this May, for example, the country expects raising renewable power’s share of its power mix to 40% by 2034, up from the current 15.1%. LNG power plants, which make up about a third of the country’s power mix, are also slated to play a prominent role, partly because the draft plan suggests that at least 24 of the nation’s 60 coal-fired plants may be converted to natural gas by 2034. The plan also suggests the country will pare down its reliance on nuclear power; it plans to shutter nine reactors and reduce nuclear’s share to 10% by 2034, down from 19% today.

New Directions for Doosan

But for Doosan, DHIC’s parent company, South Korea’s oldest business enterprise, the stakes may be even higher. While Doosan was established in 1896 as a retail business, its acquisition of DHIC (which was founded in 1962 and expanded on its own interesting trajectory) in 2001 transformed it into a formidable regional conglomerate. DHIC, which built South Korea’s first coal units, is today an established builder of coal-fired power plants globally, and Doosan relies on DHIC for nearly 20% of its revenue.

However, as with many engineering, procurement, and construction companies in the power space, it has been hard hit by the energy transition. DHIC, which attributes dismal results to a decline in foreign contract volumes as well as to domestic energy policies, has reported losses nearly every year since 2014 (except in 2017), and its operating profits have fallen dramatically from a record high 477.4 billion won in 2012 (around $438 million in 2012) to 87.7 billion won ($73.3 million) in 2019.

This April, the company’s prospects were so debilitated by the coronavirus pandemic that state-run creditors—the Export-Import Bank of Korea and the Korea Development Bank—stepped in to stave off DHIC’s “liquidity crisis” by extending a 1 trillion won ($817 million) credit line “as part of a relief package to cushion [DHIC],” as The Korea Herald reported.

The “bailout” came with the realization that if Doosan Heavy Industries failed, nearly a quarter of the electricity on Korea’s grid would be up in the air, with no other domestic companies qualified to step into Doosan Heavy’s role, observed another newspaper, Korea JoongAng Daily. But creditors also underscored the risks. “The two state-run creditors essentially want the company to restructure and separate profit-making affiliates from under its arms. They remain concerned that the financial risks from Doosan Heavy Industries’ plant-building business could extend even to its profitable affiliates,” the newspaper reported.

Analysts, too, have urged caution. “The company is struggling with a structurally unprofitable business model and is not keeping pace with the investment required to develop distinctive clean technology solutions that fast-growing Asian power markets will reward,” said financial analyst Ghee Peh, who co-authored a report scrutinizing DHIC’s finances for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis in September 2019.

It is notable, however, that DHIC doesn’t seem to have raised white flags yet, and, as it has through its pioneering history, it appears to be banking heavily on innovation to propel it forward.

Since 2017, the company has both acquired and set out to develop large capacity offshore wind technology (of between 5.5 MW and 8 MW), forayed into new wind markets in Asia, and bagged several contracts for energy storage systems, as well as for a hydrogen liquefaction demonstration. Last December, it even completed a $44 million equity investment in U.S. firm NuScale Power’s small modular reactor technology and signed a collaboration agreement to fabricate parts for the novel nuclear modules and other equipment.

Doosan Leading the National Effort

The most heavily touted of DHIC’s innovation efforts, perhaps, is its weighty participation in the South Korean national gas turbine project. The company said it has invested $830 million in research and development for the project’s flagship 270-MW class large gas turbine model—substantially more than the government’s $50 million stake—and that it is optimistic the investment will pay off. In South Korea alone, based on the 9th plan, the natural gas market “will grow explosively from the current market size of 41.3 GW in 2020 to 60.6 GW by 2034,” Hongook Park, CEO of DHIC’s Power Service Business Group, said in July.

At the end of 2019, 149 gas turbines were operating in South Korea, all which were imported, Park noted. “Given that a huge market growth is expected, we aim to further promote our company’s growth by leveraging our industry-academia-research alliances to effectively develop a top-notch Korean standard gas-fired combined cycle power plant model,” he said.

|

|

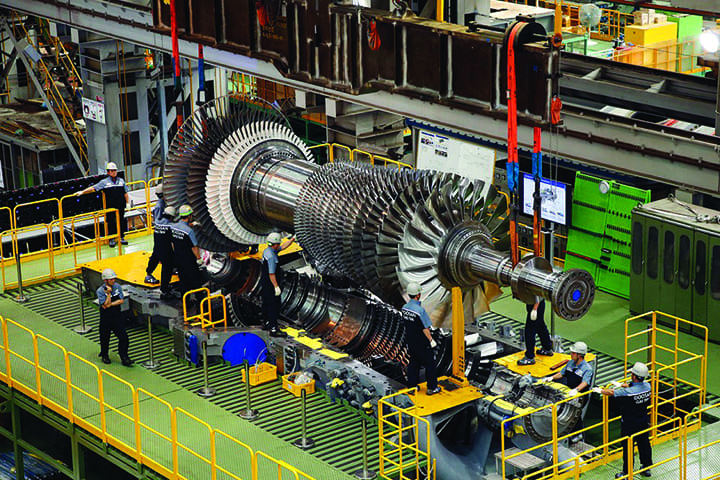

2. Doosan Heavy Industries & Construction employees working on the final assembly of the 270-MW large gas turbine model that will be demonstrated at the 500-MW liquefied natural gas–fired Gimpo Cogeneration Plant in South Korea in 2023. Courtesy: DHIC |

The company’s efforts, for now, are rooted on the DGT6-300H S1. Developed with advanced technologies—including ultra-heat-resistant alloys and precision casting, the 270-MW model has more than 40,000 parts, including 450 blades (Figure 2). It features “axial compressor technology that compresses a large volume of air to up to 24:1; a combustor technology that minimizes exhaust gas; and a system integration technology for assembling the core components of the compressor, combustor, and turbine.” These efforts have enabled a combined cycle efficiency “of more than 60%,” the company said.

DHIC completed final assembly of the 270-MW model in September 2019, and it is now testing the machine at an $83 million full-speed, full-load, sensor-loaded test center at its headquarters in Changwon before it heads to Gimpo. Plans then entail development of a 380-MW model “with the latest specifications to preemptively reflect the market changes,” as well as a 100-MW mid-sized model that is designed to cater to renewable intermittency.

In efforts to broaden its market prospects, meanwhile, DHIC has also opened offices in Florida and Switzerland. As significantly, in 2017, it acquired Doosan Turbomachinery Services, a company that “carries out the entire service business including maintenance, parts replacement, and performance improvement of the core parts of gas turbines in the United States.”

It is unclear whether this will be enough to set the company on a competitive course with other established OEMs, however. In the first half of this year, a cutthroat battle for advanced gas turbine market share intensified with historical market leader GE facing stiff competition from MHPS and Siemens. To allay business risks from what the gas turbine manufacturers point to is weakened demand for large gas turbines, GE in 2018 restructured its power unit to separate gas power from other divisions, while Siemens this April made progress in spinning off of its energy business.

—Sonal Patel is senior associate editor for POWER.