State utility regulatory commissions are realizing that their legacy practices—processing retail utility filings and intervening in federal cases—are too reactive. They wish to display more purposefulness, more decisiveness, more leadership. How can they plot their progress? First, some thoughts on metrics, arranged by three major objectives. Then, some critiques of “traditional” metrics, such as docket disposition and rate levels; and finally, some thoughts on whether the term “metrics” is even useful.

Clarify the Commission’s Regulatory Purposes

Metrics must reflect purpose. Regulation’s purpose is to align private behavior with public interest. The regulator must establish performance standards for utilities, then enforce those standards. Setting standards requires multiple value judgments.

Two examples: (1) What is the appropriate performance standard: average, superior, state-of-the-art, better-than-thy-neighbor? (2) What are the right resultants of the vectors in tension, such as economic efficiency vs. affordability; economic development vs. environmental sensitivity; speedy decisions vs. participatory procedures? These conflicts call for courage, in the form of decisiveness. To be everything to everyone is to preclude purposefulness.

Metrics: Has the commission made the necessary value judgments? If a regulator asked each of the commission’s employees (California has 800) to state the commission’s regulatory purpose, performance standards, and tension resolutions, would the answers be consistent? Does the commission have clear expectations for each utility’s performance, in terms of cost-effectiveness and innovation? Does each utility’s performance meet those expectations? Would that utility’s employees all answer the “purpose” question consistently?

Identify Regulatory Challenges

Electric and gas regulatory challenges include climate change, energy efficiency, rate design, and regional power supply planning. Added to those industry-specific challenges are those cutting across all sectors: market structure (Do we want competition or monopolies?); corporate structure (Do we want leveraged buyouts, conglomerates, and non-integrated asset collections; or do we want local companies focused on providing essential services?); infrastructure sufficiency (Will we pay for our own wear and tear, or will we bequeath those costs to our offspring?); rate design (Is it time to remove the average-cost mask, exposing the true hourly cost of consumption?); technological advances (Who should fund the demonstration projects that produce both dry holes and breakthroughs?); and workforce replacement and modernization (Where do we find the next generation of pole planters, tree trimmers, and substation designers?)

Shape the Regulatory Infrastructure to Meet the Challenges

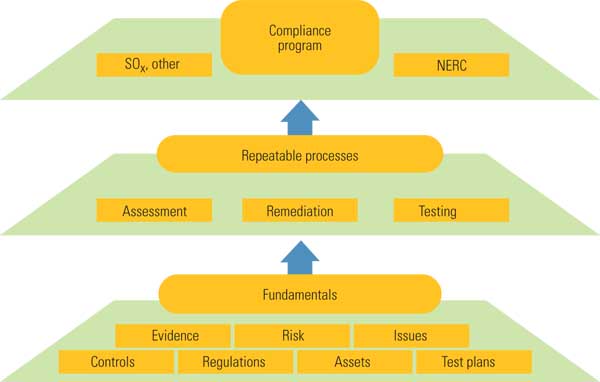

Regulatory excellence requires an accommodating infrastructure. There are five parts to that infrastructure, each with its own metrics.

1. Authority to act. Ancient regulatory statutes need systematic modernization, not piecemeal revision. Enacted a century ago, then layered with the latest urgencies and opportunities, our regulatory statutes have gaps, redundancies, and asymmetries that weaken regulatory authority.

Metrics: Given the challenges described above, do we have the statutory authority we need to produce the performance we need? Are our relations with legislators productive? Do legislators look to the commission first when problems arise?

2. Information necessary to act. Information reaches regulators unevenly: if they ask, if they have time to ask, if they think to ask, if someone chooses to supply it, is the information supplied truthful and evenhanded.

Metrics: Do we have the information, and the information-gathering processes and resources, necessary to make good decisions? Do the utilities have a duty to inform? Does the commission learn of its options sufficiently early to make decisions timely and carefully? Do they fulfill that duty timely and objectively? Is there trust?

3. Expertise necessary to act. Traditional commission expertise is silo-based: accountants, economists, engineers, lawyers; electric, gas, telecomm, water; rate cases, mergers, service quality investigations, all operating on their own terms for their own cases. These realms of expertise remain essential, but there is a risk of hammers seeing only nails. The new challenges are multidisciplinary and long-term.

Metrics: Do commissioners and staff have skills in multidisciplinary thinking and multi-year strategizing?

4. Decision-making leading to action. Many legacy procedures emphasize the reactive—awaiting utility filings at the state level, intervening as supplicants in federal venues. Reactivity risks prioritization-by-parties. Utilities initiate proceedings to advance business objectives. That’s understandable and acceptable. But the sum of these entrepreneurial efforts does not equal public interest policy. Reactivity makes regulators captive to events, not advancing ideas.

The late communications guru Marshall McLuhan (Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (1964) offers an analogy. If “medium is the message,” as McLuhan famously posited, then for regulation, procedure is the policy. The context (e.g., cinema, television, comic book, traditional book) defines the intensity of a person’s participation. The procedure (e.g., adjudication, investigation, rulemaking, cross examination, multi-party panels, informal discussions, “collaboratives,” commission-directed submissions) defines the level of regulatory commission alertness—and the quality of its leadership.

Metrics: Policymaking is both proactive and reactive. Are we getting the mix right? Do the present procedures and workloads allow the commission to lead, or only to react? Do our proceedings focus on the commission’s priorities or the stakeholder’s priorities? Are we disposing of dockets or producing performance?

5. Continuous re-evaluation: Effective regulation is continuously self-critical: It examines and re-examines its infrastructure to ensure the best fit of purposes, authorities, information, expertise, and procedures to the challenges at hand.

Metrics: Have we defined regulatory excellence? Are there re-evaluation criteria and procedures, a process for making mid-term corrections? When a commission approves a merger based on specified expectations of benefits, does a later commission assess the results?

Other Metrics: Useful and Not-So

I have identified three main goals for a regulatory commission—clarify purposes, identify challenges, shape infrastructure—and several measures by which to assess progress. Here are more metrics that together test achievement of these goals.

Advocates’ performance: Useful. Do the advocates appearing before us address commission priorities or their own objectives? Do they offer balanced positions that apply their expertise to the commission’s needs, or do they insist on their own advancement regardless of context? Do they use facts and logic, or adjectives and adverbs? Do they advance propositions that are absolute and unprovable?

Commissioner and staff time allocation: Useful. How do we spend a majority of our time: Reading objective material or reading stakeholder advocacy? Meeting with experts or meeting with parties?

Docket disposition: Not so useful. “We process cases expeditiously” is basic competence; it goes without saying. If we were evaluating a young musician for admission to Julliard, we would not say, “She plays in tune.”

Rate levels: Not so useful. “Our rates are lower than comparable states” tells us nothing about performance. Are they lower because commission policies produce better utility performance, or because the utility has deferred maintenance by shifting costs to future ratepayers and future commissioners?

Is “Metrics” Useful?

Now we can see the inadequacy of the term “metrics.” The term connotes quantifiability. But none of the useful metrics are quantifiable. A regulatory commission is not a consulting firm (metrics: billable hours and quarterly profits); regulation is not a political campaign (metrics: I lowered taxes, you increased the deficit). Even in the worlds of consulting and campaigning, real public value is unrelated to these common quantities. Measurement of value is necessary, but the currency of value remains elusive. Let’s keep thinking.

—Scott Hempling is the executive director of the National Regulatory Research Institute, based in Washington, D.C. NRRI is a project of the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners. This piece was originally published at http://nrri2.org and is reprinted with permission.