The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) deadline for placing greenhouse gas (GHG) emission limits on new fossil-fueled power plants has come and gone. Comments from EPA staff indicate little urgency in setting a new deadline. Meanwhile, prospects for FutureGen 2.0, originally developed with GHG limits in mind, are looking bleaker.

The EPA had been expected to issue its final New Source Performance Standards (NSPS) for GHG emissions by April 13, but several media outlets reported over the weekend that EPA spokeswoman Alisha Johnson wrote in an April 12 e-mail that the agency was still reviewing more than 2 million comments on its proposal.

There currently are no federal limits on carbon emissions from new power plants. In a letter sent to President Obama in mid-March, four Senate Democrats, including coal country Senator Joe Manchin (W.Va.), expressed “continued concern” about the EPA’s plans to issue GHG NSPS for new fossil fuel–fired power plants. Pushback from his own party may have been one reason for the delay.

The EPA’s acting administrator, Bob Perciasepe, told reporters last week that the agency would begin work on a rule for existing plants sometime in the next fiscal year. The delay on standards for new plants could mean that standards for both old and new power plants might be combined into one new regulation.

States, Environmental Groups Threaten Suit

On Wednesday, 11 states and a city sent the EPA a joint notice of intent to sue the agency, saying the EPA’s failure to finalize GHG standards for new power plants and emission guidelines for existing power plants violated the Clean Air Act. Environmental groups sent a separate notice to the EPA earlier this week, also threatening litigation.

The states of New York, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the District of Columbia, and New York City in 2010 reached a settlement with the EPA, in which the agency agreed to promulgate GHG rules for new and existing plants. In a letter to acting EPA Administrator Perciasepe, the states reiterated that severe droughts, heat waves, and a string of storms had experienced "substantial economic costs" and threats to public health as a result of climate disruption caused by increasing "GHG pollution."

More than 10 years have elapsed since some states and environmental groups requested that the EPA review existing standards to determine whether standards should be promulgated for GHG emissions from power plants, the states said. Six years ago, they pointed out, the EPA had refused to establish GHG standards based on the rationale that it was rejected by the Supreme Court in Massachusetts v. EPA, and three more years had elapsed since the EPA declared that GHG emissions endanger public health and welfare.

"Given the urgent need for agency action due to the adverse effects on human health and welfare from climate change already being experienced, any further delay by EPA in finalizing standards of performance and related emission guidelines for [GHG] emissions from power plants is unwarranted and unreasonable," the states said.

The states and environmental groups separately gave the EPA 60 days to finalize the GHG rules; should the agency miss that deadline, it would face a lawsuit in federal district court.

Wider Implications for FutureGen

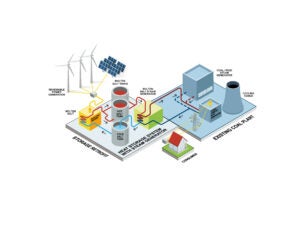

In April 2012, the EPA said its proposed standard “is flexible, achievable and can be met by a variety of facilities using different fossil fuels, such as natural gas and coal.” However, many have argued that new coal plants, using currently available technologies, would not be able to meet the proposed output-based emission standard of 1,000 pounds of CO2/MWh gross). The rule was to apply to new fossil fuel–fired boilers, integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) units, and natural gas combined cycle units. Flexibility included an option for averaging 30 years of CO2 emissions to meet the proposed standard, in the expectation that carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology would mature over time.

However, CCS technologies are struggling to make headway, and the troubled government-supported FutureGen project, planned to integrate CCS with IGCC technology, may never come online. The project, initiated in 2003, has been restructured twice. As an April 3 report from the Congressional Research Service says, “Nearly ten years and two restructuring efforts since FutureGen’s inception, the project is still in its early development stages.”

As the report notes, the project’s current challenges include “rising costs of production, ongoing issues with project development, lack of incentives for investment from the private sector, time constraints, and competition with foreign nations. Remaining challenges to FutureGen’s development include securing private sector funding to meet increasing costs, purchasing the power plant for the project, obtaining permission from DOE to retrofit the plant, performing the retrofit, and then meeting the goal of 90% capture of CO2.”

The private investment part of the public-private partnership is hampered because, as the report explains, without GHG regulation such as the anticipated and now-stalled NSPS, there is little financial incentive for investment in cleaner-burning, but more expensive, coal technologies. China is now poised to take the lead in clean coal technologies, and the report concludes that full-scale CCS demonstration at FutureGen 2.0 by 2015 (the year that $1 billion in federal stimulus funding for the project expires) will be “difficult to accomplish.”

The report concludes by looking at additional factors that contribute to a gloomy outlook for FutureGen. For one, low-cost gas may economically discourage the government and industry from pursuing CCS research. Critics of GHG regulation (a primary rationale for the project’s development and continued funding) cite concern over the loss of jobs in coal-based industries, which could put a damper on such regulation.

The report also points to an international policy imbalance issue: “While U.S. policies and regulations call into question the utilization of coal for electricity generation at current levels, the United States continues its international financial assistance to foreign nations like China for their development of global climate change initiatives. Effectively, the United States is helping to develop CCS technologies in foreign countries while domestic CCS projects, including FutureGen, are still in their early stages of construction. An important question policymakers may consider is whether the United States should continue to fund foreign CCS technologies while decreasing domestic coal production and utilization through new regulations.”

Sources: POWER, EPA, Congressional Research Office, Washington Post, New York Times

—Gail Reitenbach, PhD, Managing Editor (@POWERmagazine, @GailReit); Sonal Patel, Senior Writer (@sonalcpatel)

This story, originally published on April 15, was updated on April 18.