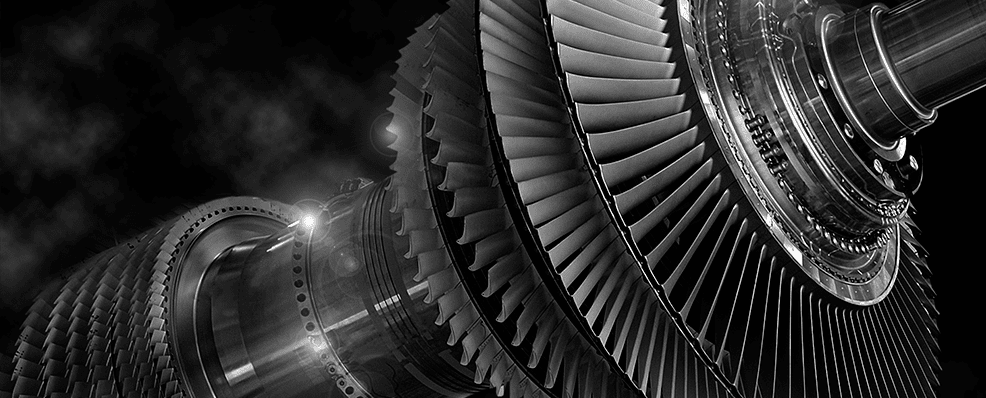

German energy giant RWE will in September acquire Vattenfall’s 1.4-GW Magnum combined cycle gas-fired power station, a project in the Netherlands where work is underway to explore converting one of the three 440-MW Mitsubishi Power M701F power blocks to 100% hydrogen by 2025.

Vattenfall on June 2 said RWE agreed to take over the 2013-completed plant in Eemshaven, Groningen province (Figure 1), in a €500 million ($564.95 million) deal. The deal comes a year after the company first indicated it was considering selling the “profitable and state-of-the-art” gas-fired plant, which plays an integral role in the Netherlands’ energy security.

|

|

1. The 1.4-GW Magnum combined cycle power plant is located in Eemshaven, Netherlands. Completed in 2013, it features three 440-MW Mitsubishi Power M701F power blocks. Courtesy: Vattenfall |

An Energy Crisis With Few Solutions

The deal is notable given recent events that have rocked the Netherlands’ energy security. On May 31, Russian state energy giant Gazprom moved to halt gas flows to GasTerra, a wholesale gas trader that buys and trades gas on behalf of the Dutch government. According to GasTerra, the dispute stems from the Russian government’s March 31 decree requiring Russian gas payments in roubles.

“This means that anyone wanting to buy gas would have to open both a euro and a rouble account with Gazprombank in Moscow,” GasTerra explained. “GasTerra will not go along with Gazprom’s payment demands. This is because to do so would risk breaching sanctions imposed by the [European Union] and also because there are too many financial and operational risks associated with the required payment route,” it said.

The dispute will mean that until Oct. 1, at least, Gazprom will deny delivery of 2 billion cubic meters of contracted gas. GasTerra anticipates buying gas from other providers in the European gas market. However, it noted it could “not predict” how the loss of the contracted gas will affect the Netherlands’ gas supply and demand or “whether the European market can absorb this loss of supply without serious consequences.” The dispute echoes Russia’s earlier gas cutoffs to Finland, Poland, and Bulgaria, as well as to Danish energy firm Ørsted and Shell Energy for contracted supplies to Germany—events that have roiled gas prices in Europe, and heightened an energy crisis that began brewing last year.

Russia has so far supplied about 15% of the Netherlands’ gas, but about 44% of Dutch energy usage is based on gas, according to government figures. The trade dispute, meanwhile, follows the Dutch government’s April 2022 announced intention—as a response to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine—to wind down its dependence on coal, oil, and gas from Russia “as quickly as is practicable and preferably by the end of this year.” The Dutch government was notably counting on good preparations for the winter, ensuring that gas reserves were well-stocked and more liquefied natural gas (LNG) could be imported from Norway and other countries.

The Dutch government’s plans also include energy conservation and a general speed-up of a transition to sustainable energy sources. The Netherlands, notably, has been exploring a reduced reliance on natural gas since 2012, when gas extraction at Groningen, Europe’s largest onshore natural gas field, was identified as the cause of earthquakes in the north of the country.

Citing safety measures, the government in March 2018 decided to phase out production from the giant gas field by 2030. Fueled by public outrage and support for sustainability, the government later moved that target up to October 2023. Momentum from that measure contributed to the Dutch government’s 2019 enactment of “Klimaatakkoord,” which envisions that all dwellings and other buildings should be heated without natural gas by 2050.

Vattenfall Seeking New Horizons

According to Vattenfall, a company wholly owned by the government of Sweden, these changes are aligned with the company’s recently revised investment strategy, which it says effectively “reflects a 1.5-degree target” and a “goal of fossil-free living within one generation.” In June, Alexander van Ofwegen, head of Vattenfall’s Dutch Heat operations and CFO for Vattenfall in the Netherlands, said, “At the heart of Vattenfall’s Heat operations is, however, the district heating and cooling business where Vattenfall is focusing on decarbonizing the heat supply to their customers as part of the gas phase-out in the Netherlands.” Proceeds from the transaction will give the Swedish company “more resources to invest in the energy transition, such as offshore wind, and district heating and cooling,” he added.

A decade ago, as Vattenfall was preparing to bring the Magnum combined cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) online, it was grappling with billions of euros in losses associated with rapid changes in European energy markets, which were characterized by a surplus of generation capacity, mainly from overproduction of renewables, and weak demand.

The conditions put immense pressure on conventional gas and hard coal–based generation, forcing the company to impair most of its coal and gas assets in the Netherlands and elsewhere. These included the Magnum facility, which began official operation with only one of its three units running.

Magnum Originally Developed as an IGCC Project

As originally conceived in 2008, Magnum was designed as an integrated gasification combined cycle plant, capable of running on multiple fuels, including biomass, gas, and coal. Vattenfall ultimately decided that the facility, which is located near a modern seaport, with availability of space and infrastructure, and with a good connection to the existing high-voltage and natural gas grid, was better suited as a gas-fired station.

The CCGT project today comprises three Mitsubishi Power M701F units, each composed of a heat recovery steam generator, a gas turbine, a steam turbine, and a generator. “This technology ensures a very favorable output (about 58%),” Vattenfall has said. The plant, pivotally, also has black-start capability, as well as a solar park comprising more than 17,000 panels with a maximum production capacity of 5.6 MWe.

Meanwhile, in 2017, Vattenfall, auto thermal reforming plant developer Equinor, and gas grid infrastructure firm Gasunie contracted Mitsubishi Power to investigate the technical feasibility of hydrogen firing at one of Magnum’s three 440-MW CCGT units. The project, known as the “Hydrogen to Magnum” (H2M), envisions running the unit 100% on blue hydrogen processed from Norwegian natural gas by 2025 and then gradually transitioning it to non-fossil hydrogen.

So far, an initial feasibility study has been completed, but “evaluation, planning, and design of specific modification ranges in the gas turbine technological field continue to be conducted by Mitsubishi Power,” said Mitsubishi Power’s parent company Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

|

|

2. RWE’s 1.6-GW Eemshaven power station near Groningen, Netherlands, is an ultrasupercritical plant that is fired with hard coal and biomass. Completed in 2015, the plant reportedly achieves an efficiency level of 46%. About 15% of the plant’s power comes from biomass, and RWE has considered converting the plant to biomass in the long term, “if it is economically feasible and the right permits are in place.” Courtesy: RWE |

RWE Envisions a Massive Hydrogen Hub in Eemshaven

For Essen, Germany–headquartered RWE, Magnum’s acquisition represents an opportunity to develop Eemshaven into one of the leading energy and hydrogen hubs in Northwest Europe. Magnum is located in the “immediate vicinity” of RWE’s 1.56-GW Eemshaven station, a hard coal- and biomass-fired power plant (Figure 2). Since 2020, RWE has explored adding 600 MW of electrolyzers to the Eemshaven plant fed by the 760-MW Hollandse Kust West (HKW) VII offshore wind farm, in a project it calls “Eemshydrogen.” RWE envisions chemical plants in the nearby industrial cluster in Delfzijl may be potential buyers of the green hydrogen. At Groningen province’s Eemshaven port, near Magnum, Gasunie is meanwhile developing LNG terminals, which could be additionally supported by heat supplied from Magnum and Eemshaven.

RWE this year submitted bids for both the HKW VI and VII sites (each 760 MW) to contribute to the Dutch government’s ambitious build-out target of 21 GW for offshore wind by about 2030. The proposed design concept for HKW VI, notably, integrates innovations to be implemented to allow birds and bats to fly safely between the turbines and under the rotor swept area,” the company said.

Roger Miesen, CEO of RWE Generation SE, in June noted the hub’s nearness to the Dutch North Sea and how the surrounding former natural gas fields could also allow Magnum and RWE’s Eemshaven plant to use carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies in the future, allowing the Eemshaven site to be operated “as not just CO 2 neutral, but with a negative CO 2 output.” RWE is hoping to get the necessary government support to make the project “technically, politically, and economically feasible,” it noted.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).