A handful of geothermal projects are crossing from experimentation into execution, testing whether drilling gains, reservoir control, and new market demand can turn subsurface risk into firm, contractable power.

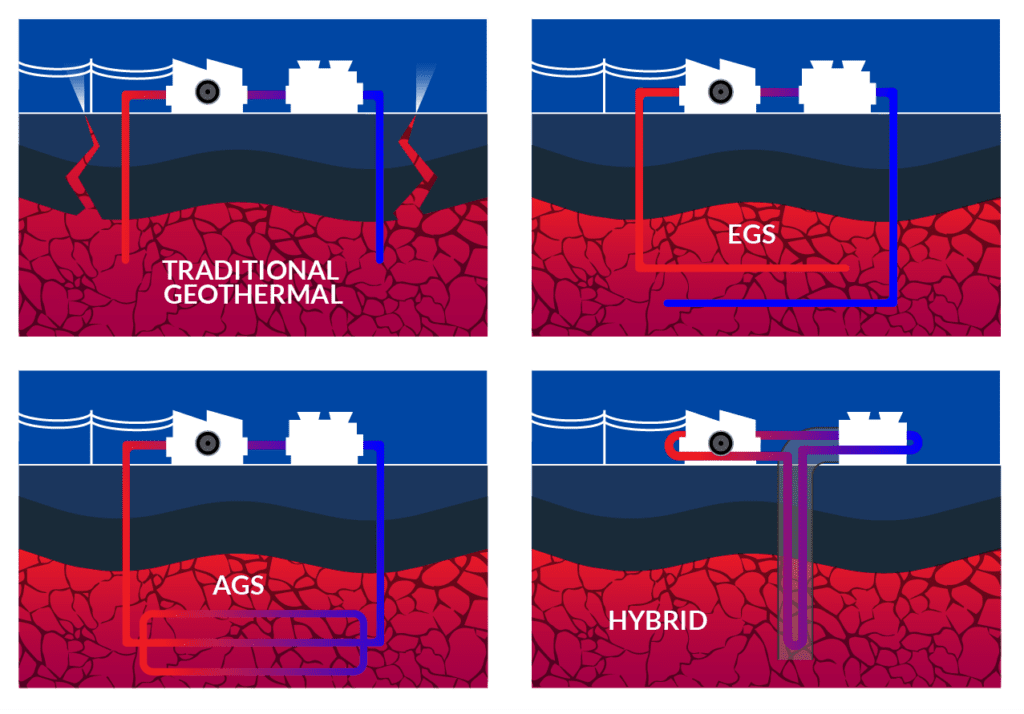

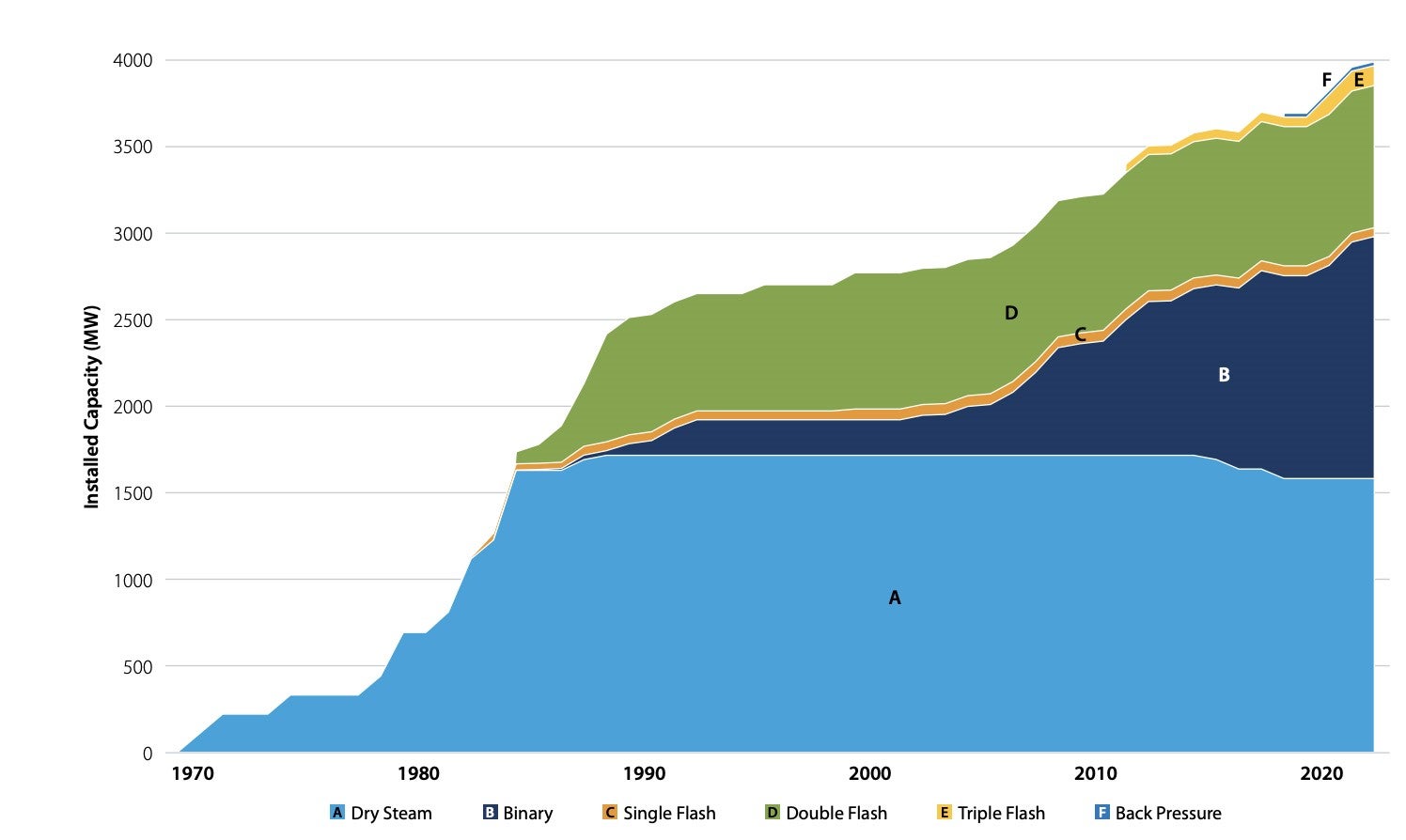

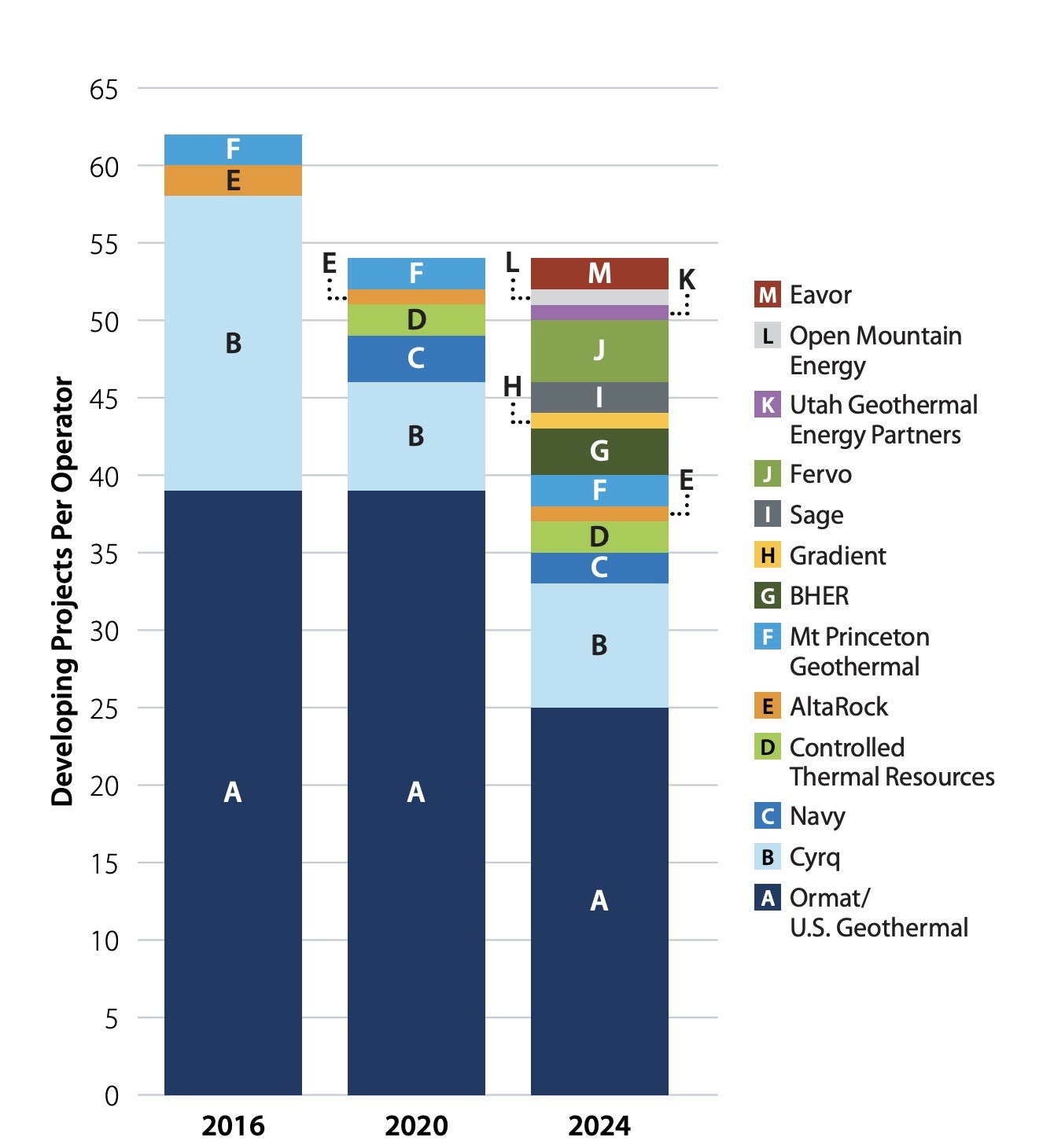

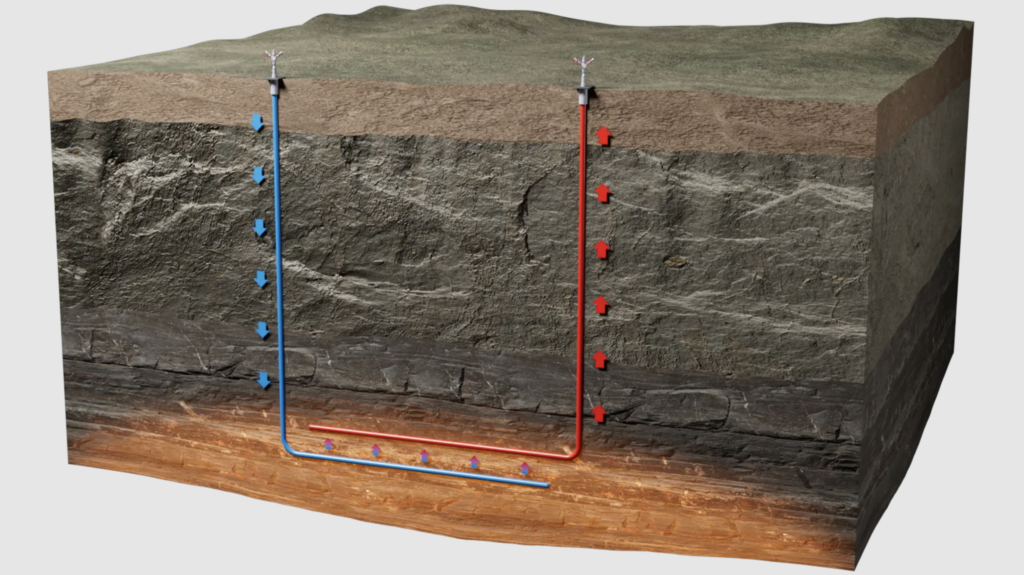

Since 2021, geothermal power’s proposition has been quietly shifting, driven primarily by encouraging policy, but also a new class of decisive buyers. In response to reliability concerns and rising demand for firm power, utilities, corporations, and data center operators have signed dozens of new power agreements. But, as the 2025 U.S. Geothermal Market Report, released in January 2026 by the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR, formerly the National Renewable Energy Laboratory) and Geothermal Rising, shows, the commercial activity, long centered on conventional geothermal (Figure 1), has morphed into fresh support for emerging geothermal technologies, including enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) and advanced (closed-loop) geothermal (CLG).

According to the report, a collaborative effort that updates a landmark 2021 U.S. industry-federal assessment, next-generation geothermal systems now account for 60% of all geothermal power purchase agreements (PPAs) signed between 2021 and mid-2025—a remarkable pivot for a technology that secured its first commercial PPA only in 2022. Utilities have procured or agreed to procure 984 MW of next-generation capacity across California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and locations east of the Rocky Mountains through 11 PPAs. The report also notes that while companies at the forefront of developing and commercializing these technologies have raised more than $1.5 billion in private capital since 2021, enhanced geothermal and closed-loop technology companies brought in $990 million and $604 million, respectively, between 2021 and mid-2025.

That momentum, meanwhile, also has international traction. In a January update, the International Energy Agency (IEA) revealed that financing for next-generation geothermal reached nearly $2.2 billion in 2025—an 80% year-over-year increase from just $22 million in 2018. Conventional geothermal attracted nearly $5 billion in funding in 2025, a four-fold increase from 2018, while geothermal heating projects secured more than $11.5 billion in 2025 alone. In another key finding, the IEA analysis suggests that investor confidence is maturing, noting that the global share of equity financing declined from 70% between 2018 and 2020 to just over half between 2023 and 2025, as companies increasingly secured debt alongside data center power and critical mineral supply agreements.

Three Forces Converging on Next-Generation Geothermal

For now, the reports point to three overlapping forces that appear to be accelerating a transition to next-generation geothermal (Figure 2), propelling them from pilot-stage experimentation toward commercial relevance. These include rapid technology gains, a market shift that places new value on firm power, and policy frameworks designed to absorb early risk.

First, drilling and subsurface engineering advances are materially changing project economics. The 2025 U.S. Geothermal Market Report documents measurable performance improvements at both government-backed testbeds and private-sector developments. At the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Utah Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE), drilling performance has improved substantially over a short period. The report notes that “reduction in on-bottom drilling hours” has been a defining outcome of recent campaigns, with drilling rates improving from roughly 8 meters per hour (m/hr) in early campaigns to nearly 15 m/hr by 2024, and peak rates reaching 26 m/hr during select intervals.

The gains are being replicated at Fervo Energy’s Cape Station in Utah, where the EGS firm reported drilling rates of 30 m/hr and a reduction in drilling costs to roughly $350 per foot. Many improvements, which include “advances in polycrystalline diamond compact bit design and use of physics-based techniques to optimize mechanical specific energy and maximize sustained rate of penetration,” derive directly from shale oil and gas practices. Innovations have helped cut well costs by up to 30% while meeting expectations that asset lifetimes can extend beyond 25 years, the report suggests.

Meanwhile, electricity markets are beginning to pay explicitly for firm, always-available power. The report also suggests that next-generation geothermal projects are no longer competing solely on energy price against variable renewables. Until 2023, most developers “could only secure electricity price guarantees equivalent to solar and wind projects,” typically in the range of $30/MWh to $60/MWh, it notes, but that pricing dynamic has changed as load growth accelerates and reliability constraints sharpen, particularly in data-center-heavy regions.

According to the IEA, geothermal’s appeal lies in its ability to provide “an around-the-clock, low-emissions source of power,” particularly as “power systems place a growing premium on firm supply.” The IEA notes that developers are now securing higher-value contracts, including with big tech players, noting that some agreements are reaching about $130/MWh. Google’s 115-MW agreement with Fervo Energy and Meta’s commitments to source 150 MW from Sage Geosystems and additional capacity from XGS Energy illustrate that this premium pricing extends even to first-of-a-kind projects.

Third, policy interventions are deliberately targeting early-stage risk. Both U.S. and international analyses emphasize that next-generation geothermal remains highly capital-intensive and exposed to significant upfront uncertainty. Geothermal projects “remain among the most capital-intensive in the energy sector, with drilling and well costs often representing up to 80% of total costs,” placing many developments in what it calls the “technology valley of death,” where projects are “too big for venture capitalists alone and too risky for established corporate energy players,” the IEA notes. Bridging that gap, however, are targeted policy tools—including the DOE’s geothermal research and development funding, Germany’s accelerated permitting paired with drilling risk insurance, and risk-mitigation facilities in the Philippines, Germany, and East Africa.

Groundbreakers: Projects Redefining What Geothermal Can Do

So far, a small but growing set of geothermal projects are moving beyond theory and pilot-scale promise to test what next generation technologies can deliver under commercial conditions.

Fervo Cape Station Phase 1: Proving EGS Economics at Commercial Scale. Fervo Energy’s Cape Station in Beaver County, Utah (Figure 3), represents the Houston-based company’s effort to scale EGS from pilot scale to utility-grade capacity, with a planned 500-MW buildout—100 MW in Phase 1 targeted for 2026 and 400 MW in Phase 2 by 2028. The project draws directly from Project Red in Nevada, which in 2023 became the first commercially viable EGS by demonstrating that an enhanced geothermal resource could be drilled, stimulated, tested, and integrated into an existing utility-scale power plant without new grid infrastructure. Project Red delivered 3.5 MW, sustained peak production of 63 kilograms per second (kg/s) at 191C for 37 consecutive days, and began supplying power to NV Energy’s Blue Mountain facility in November 2023 under a standard PPA.

Cape Station’s significance lies in demonstrating that EGS economics can work at a commercial scale. As of September 2024, 15 wells had been drilled at the site, with 29 planned for Phase 1. Drilling costs have fallen from roughly $1,050 per foot at Project Red to an average of $450 to $550 per foot at Cape Station, with the best wells approaching $350 per foot; recent appraisal wells were drilled in just 16 days. According to the company, 30-day testing has achieved flow rates of up to 107 kg/s—enabling more than 10 MW per production well, roughly triple Project Red’s per-well output. Through 2024, the project secured $973 million in financing ($642 million equity and $331 million debt), marking the first large-scale institutional lending for EGS, and all 500 MW of capacity is fully contracted, led by Southern California Edison, Shell Energy, and California community choice aggregators.

Operational momentum has continued into 2025. Fervo reports that nearly all Phase 1 wells have now been drilled, including 12 completed between April and October 2025, one of the most active drilling periods to date. Wells feature laterals averaging about 5,000 feet, supported by dense subsurface monitoring using fiber-optic cables, borehole seismometers, and surface nodal arrays. In testimony before the House Natural Resources Subcommittee in December 2025, CEO Tim Latimer emphasized the pace of improvement, stating, “We’ve already shown a 75% reduction in drilling time and a 70% cost per foot reduction since 2022.” He also highlighted a mid-2025 milestone in which Fervo drilled a 16,000-foot well in 16 days at bottomhole temperatures approaching 520F—a 79% reduction relative to DOE baselines—strengthening the case for EGS deployment well beyond traditional geothermal regions.

Halliburton Supports Integrated Geothermal ExecutionFor decades, geothermal development remained constrained by site-specific geology, limited deployment, and high upfront risk. Halliburton has operated in that space for more than 70 years, historically providing discrete services adapted from oil and gas. Over the past several years, however, the company has evolved that role, shifting from product supply toward integrated execution as geothermal projects move deeper and hotter. “Today, the company is helping customers redefine what’s possible in this sector through first-of-a-kind projects,” Halliburton told POWER, citing collaborations with Fervo Energy at Cape Station, Mazama Energy’s Newberry superhot enhanced geothermal system (EGS) pilot—which achieved record temperatures of 331C—and GeoFrame Energy’s lithium-geothermal development. “We’re seeing a fundamentally different level of technical ambition and commercial risk in today’s geothermal projects,” the company said, pointing to EGS, closed-loop designs, and hybrid geothermal–industrial applications that place new demands on subsurface execution. Rather than engaging late in the development cycle, Halliburton is increasingly involved earlier, coordinating drilling, cementing, reservoir modeling, and project planning to help projects move from pilot-scale experimentation toward commercial deployment. “One of the big differences Halliburton is seeing is the support needed from new energy ventures, compared to traditional O&G,” the company said. “Deeper, more integrated support is required for complicated projects, which are often pilot tests or early adopters for the industry. Larger operators need footprint, logistics, and integrated capabilities, [while] smaller operators need well engineering, design expertise, and exploration of subsurface.” Halliburton consolidated its geothermal capabilities into a dedicated Low Carbon Solutions portfolio, aligning technologies and engineering teams traditionally spread across oil and gas service lines to manage heat extraction, well integrity, and operational risk within a single execution framework. “These are not one-off wells,” the company noted. “Developers are asking for systems that can scale, operate for decades, and perform under extreme thermal and mechanical conditions.” Expanding Geographic Reach Through EGSTraditional geothermal systems, known as hydrothermal, require high-temperature reservoirs, in-situ water, and permeability—all in the same location. While hydrothermal systems have been used for more than a century, the geographic scarcity of these unique subsurface conditions limits their widespread application. Today, only 1% of U.S. electricity generation comes from geothermal resources—though geothermal “could account for 8% of power in the U.S. by 2050,” according to industry projections. Unlike hydrothermal systems, EGS do not rely on all three geologic conditions in the same location. Technologies pioneered by the oil and gas industry, such as horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, allow developers to create permeability and introduce water to harness heat from hot, dry rock. Water is pumped down an injection well and travels through permeable fractures where it captures heat before returning to the surface via a production well to power a turbine. Advanced geothermal systems (AGS) harvest heat from hot, dry rock in a closed-loop system, transferring heat conductively through the casing without contacting the reservoir. These systems range from single-well designs to complex multi-well projects with subsurface intersections. Supercritical geothermal systems tap extremely high-temperature and high-pressure conditions—typically above 374°C and 22.1 MPa—where water exists in a supercritical state, offering higher well productivity despite technical challenges including harsh drilling and aggressive fluid chemistry. Halliburton’s response has been to import execution disciplines honed in unconventional oil and gas—well architecture optimization, thermal-cycle-resistant barrier design, high-temperature fluids, and complex logistics coordination. “Regardless of the type of geothermal system, Halliburton designs and constructs solutions for the life of the asset,” the company said. Cape Station as a Proof PointThat model has been tested most visibly at Fervo Energy’s Cape Station project in Beaver County, Utah, one of the first attempts to deploy EGS at commercial scale. At Cape Station, Fervo and Halliburton began their collaboration around well integrity. To handle high temperatures, ultra-hard granite, and repeated thermal cycling, Fervo selected Halliburton’s VersaFlex® expandable liner hanger system as the backbone of the production casing program, providing the isolation and load capacity needed to maintain zonal integrity in long, deviated wells while giving designers flexibility to adapt as the program evolved.  Cementing quickly became the second critical pillar. Conventional Portland-based formulations can degrade under prolonged exposure to EGS temperatures and thermal cycling. Halliburton engineered a non-Portland cement blend tailored to Cape Station’s bottomhole circulation temperatures and thermal profile. While early designs were intentionally conservative, as operating data accumulated, the company and Fervo iterated to slurry recipes that preserved long-term compressive strength and bond quality while trimming material cost and placement risk. Barrier design, Halliburton stressed, is “one of the most difficult but critical parts of geothermal well construction,” requiring annular seals that can withstand high production temperatures, lost circulation, corrosive fluids, pressure variations, and thermal cycling. Logistics added another layer of complexity. Cape Station’s remote Utah location required cement to be blended in Bakersfield, California, and trucked more than 400 miles to the site, with narrow windows for each job. Halliburton worked with Fervo to batch cement for multiple wells and stage supplies at the pad, reducing long-haul truck trips and shortening transition times between drilling phases. The approach cut emissions and safety exposure while reducing rig standby time. “We’ve had a lot of progress on cementing, both in terms of achieving our primary cement objectives and demonstrating that the wells, post-cementing, have the integrity that we need to complete them the way we intend,” said Kareem El-Sadi, drilling engineering lead at Fervo Energy. “Working with Halliburton has provided a very quick turnaround time in terms of redesigning slurries and changing our plans as we learn more about the wells.” Fluids Tailored for Hot, Hard RockAs the program advanced, collaboration expanded to drilling fluids. In Cape Station’s high-temperature granite intervals, early wells encountered foaming, fluid losses, and rheological challenges that constrained penetration rates and complicated surface handling. Halliburton’s Baroid unit developed customized fluid systems formulated to stabilize cuttings transport, reduce aeration, and manage downhole pressures while preserving toolface control in long laterals. Those tailored systems reduced surface fluid consumption by more than 80% and cut defoamer usage in certain production sections by more than half. As designs and execution practices matured across liners, cement, and fluids, drilling performance improved dramatically. Fervo reports that individual well times at Cape Station fell below 20 days as the program progressed, resulting in roughly a 70% reduction in drilling time compared to Fervo’s earlier Project Red demonstration at the Utah FORGE site. Beyond Utah: Diverse ApplicationsHalliburton’s geothermal work now spans conventional hydrothermal fields, EGS, closed-loop systems, and early superhot geothermal efforts. The company’s portfolio includes GeoFrame Energy’s Smackover formation project, which integrates geothermal energy with direct lithium extraction (DLE) from subsurface brines at approximately 12,000 feet (see sidebar, “Securing Domestic Lithium While Powering Remote Texas”). With 9,000 acres under development requiring 34 production wells and 21 injection wells, Halliburton’s project management and reservoir engineering teams helped model fluid pressures, select downhole pumps, and design wellhead equipment for both extraction and reinjection. “The collaboration with Halliburton allowed us to design a system that maintains the integrity of the Smackover formation, preserves lithium concentrations, and ensures long-term operational success,” said Bruce Cutright, CEO of GeoFrame Energy. More work is underway. The company plans to collect samples from highly reactive clay zones for analysis and proper inhibition mechanisms, allowing operators like Fervo to predict and prevent risks before they occur. New lubricants are in development to mitigate future foaming risks. The company’s work now extends to support AGS operations with artificial lift pumps and advanced digital platforms that enhance efficiency, safety, and system integrity. In supercritical geothermal environments, Halliburton’s expertise in subsurface insight and well integrity will help support reliable and safe operations, the company said. |

Utah FORGE: De-Risking EGS Reservoir Connectivity and Seismicity. The DOE’s Utah FORGE site, which sits adjacent to Fervo Energy’s Cape Station in Beaver County, Utah, completed a 28-day continuous circulation test between August and early September 2024 that directly addressed two longstanding barriers to EGS commercialization: reservoir sustainability and induced seismicity control. Since 2017, seven wells have been drilled at the site, including paired deviated injection and production wells—16A(78)-32 and 16B(78)-32—linked by a multistage hydraulically stimulated fracture network completed in March 2024.

During the circulation trial, cold water injected into the reservoir was produced at stable temperatures of approximately 185C to 196C. “In early September 2024, a 28-day circulation test was completed at Utah FORGE, during which 15 MW of thermal power was continuously produced, fulfilling a major milestone,” said Stuart Simmons, a geoscientist on the Utah FORGE team. Tracer testing and downhole diagnostics confirmed that flow remained confined to the engineered fracture network rather than dispersing into uncontrolled pathways, validating reservoir connectivity without excessive fluid loss.

Induced seismicity was monitored using a dense surface and subsurface seismic network and actively managed through a traffic-light protocol. Simmons emphasized that the site’s low-to-moderate natural seismicity, combined with real-time monitoring, enabled effective risk control during stimulation and circulation. While FORGE does not generate commercial electricity, the test produced critical performance data that underpinned DOE’s February 2024 awards for EGS pilot demonstrations and helped de-risk private financing for projects such as Fervo’s Cape Station.

Sage Geosystems–Ormat Partnership: Pressure Geothermal Brownfield Deployment. In January 2026, Houston-based Sage Geosystems joined forces with Ormat Technologies to deploy the world’s first commercial Pressure Geothermal power generation facility at an existing geothermal plant in Nevada. The project, which will leverage brownfield infrastructure to de-risk execution and accelerate timelines, will drill deeper beneath an Ormat conventional geothermal site to access hot dry rock, deploying Sage’s proprietary Geopressured Geothermal System (GGS)—a single-well EGS variant using controlled pressurization to create vertical fractures in low-permeability formations without requiring paired injection-production well doublets. By utilizing Ormat’s existing turbines, grid connections, and offtake agreements, the partnership eliminates permitting, interconnection, and surface plant construction delays, reducing development timelines by 1.5–2 years compared to greenfield projects. The facility will produce 4–6 MWe and targets online status in 2027.

The technology’s commercial viability was validated through Sage’s San Miguel Electric Cooperative Inc. (SMECI) Well #1 in Christine, Texas, which achieved 70–75% roundtrip efficiency, 17-hour discharge capability, and <2% water loss while operating as the world’s first commercial-scale pressure geothermal energy storage facility. Commissioned in August 2025 and grid-interconnected in December 2025, the project was a POWER Top Plant last year.

The Ormat partnership signals Tier-1 industry validation. In January 2026, Ormat co-led Sage’s $97 million Series B funding alongside Carbon Direct Capital, bringing total equity raised to $114 million. While Ormat CEO Doron Blachar emphasized that the collaboration aims to “significantly reduce the time and costs needed to bring EGS to market,” Sage CEO Cindy Taff has described the Nevada facility as validating “the technology and allows us to scale it quicker” ahead of the company’s 150-MWe PPA with Meta Platforms, signed in August 2024 (with a 2027 commissioning target), to supply data center baseload power. Additional government validation includes a $1.9 million U.S. Air Force grant awarded in September 2024 and Department of War contracts for Naval Air Station Corpus Christi and Marine Corps Air-Ground Combat Center Twenty-Nine Palms, both awarded in August 2025. If the Ormat deployment meets targets in 2026–2027 and the Meta project achieves its 2027 commissioning milestone, Sage’s single-well pressure geothermal architecture could become a preferred EGS design for sedimentary basins and brownfield expansions.

Eavor Geretsried Commercial Deployment: First Closed-Loop Grid Delivery. Eavor Technologies’ Geretsried project in Bavaria, Germany, achieved a technical milestone in December 2025 by delivering its first electricity to the commercial grid from a CLG system. The project validates that sealed-wellbore multilateral drilling at 4.5-kilometer (km) depth can produce power without requiring natural reservoir permeability or subsurface water interaction. Construction began in October 2022, and drilling commenced in July 2023 to build four planned Eavor-Loop installations, targeting an aggregate electric output of 8.2 MWe (or 64 MWth in district heating mode).

As of January 2026, one loop has been commissioned and is delivering power to the German grid. Each loop comprises two vertical wells with six horizontal laterals sidetracked from each (12 total per loop), connected underground via magnetic ranging to form a 16-km continuous wellbore radiator. The work builds on previous projects, including the first two-leg multilateral deep geothermal well in the U.S. in New Mexico. “In that project, Eavor drilled a single vertical well with a sidetrack to a true vertical depth of 18,000 ft and rock temperature of 250C, a first in the U.S. geothermal industry,” the NLR report notes.

While Geretsried represents a first-of-a-kind demonstration project, it is heavily supported by public financing (€136.6 million in grants and subsidized debt) and Germany’s €250/MWh feed-in tariff. The project secured €350 million in total investment, including €91.6 million European Union Innovation Fund grant and €45 million European Investment Bank debt. Eavor documented a 50% reduction in drilling time and an improvement in bit performance across successive laterals, demonstrating CLG learning potential. Still, commercial viability will depend on performance from remaining loops through 2026–2027 and whether costs can approach market competitiveness in future deployments. Eavor, notably, signed a 20-MWe PPA with NV Energy in 2022 for potential U.S. expansion.

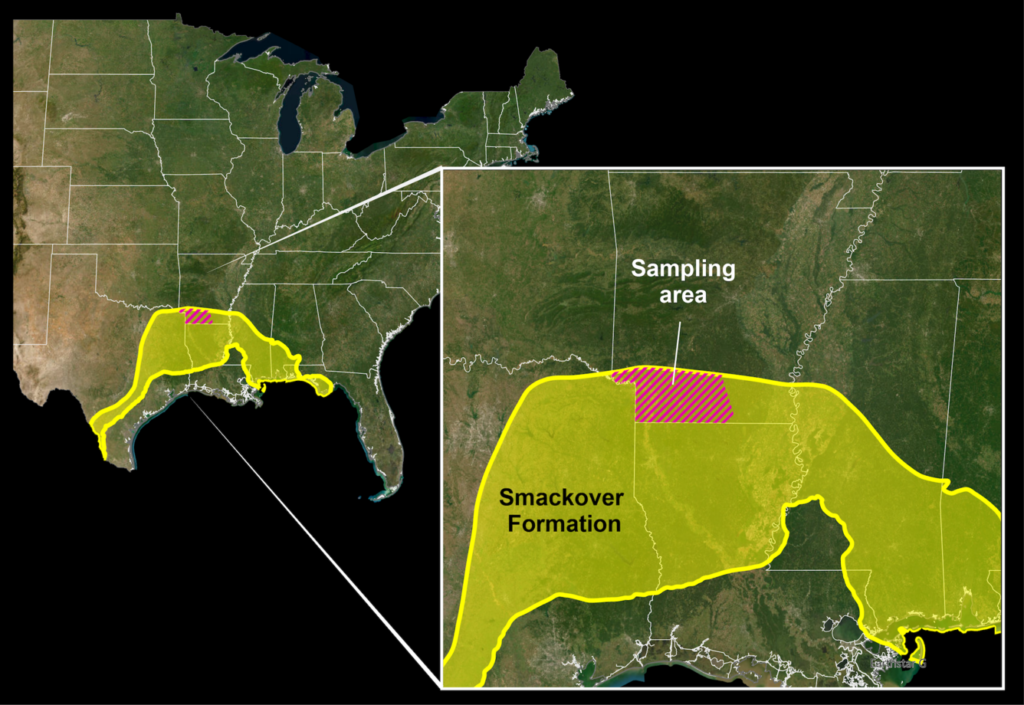

Securing Domestic Lithium While Powering Remote TexasIn June 2025, Halliburton secured a contract to design and plan demonstration-phase wells for GeoFrame Energy, a leader in green lithium carbonate and geothermal energy production, for its integrated geothermal and direct lithium extraction (DLE) project in the Smackover Formation in East Texas. The project represents the first U.S. effort to produce battery-grade lithium carbonate from the formation while generating renewable electricity to power its own operations and contribute to a stable domestic lithium supply chain. The innovative closed-loop system brings subsurface water at 275F from approximately 12,000 feet underground to the surface under carefully controlled pressure. Hot brine first passes through heat exchangers where extracted heat vaporizes a working fluid that drives turbines to generate geothermal electricity, powering the DLE operations. Once cooled, the fluid enters the DLE system where solvents selectively bind to lithium ions, producing battery-grade lithium carbonate. The remaining brine is either reinjected into a shallower subsurface horizon or potentially desalinated for agricultural use. Halliburton’s project management and reservoir engineering teams played an essential role in designing the field layout for 9,000 acres under development, optimally placing 34 production wells and 21 injection wells to avoid interference and maximize efficiency. The collaboration helped model fluid pressures, select downhole pumps, and design wellhead equipment for both extraction and reinjection—critical in a region with limited historical data. The project is already generating positive local impact in Mount Vernon, Texas, with revenue flowing back to support schools and public services, and plans to eventually contribute electricity to the municipal power grid. For more information on how geothermal energy powers this groundbreaking lithium extraction project, read the full interview with GeoFrame Energy’s Chief Geologist Laura Zahm on Halliburton’s Energy Pulse blog.

|

On The Horizon

While near-term growth in geothermal power is being driven by EGS and closed-loop deployments, a wider set of emerging technologies and applications are also poised to reshape geothermal’s long-term role.

One notable frontier is superhot geothermal, which targets fluids above the critical point of water (374C, 221 bar). At these temperatures, individual wells could deliver five to 10 times the energy output of conventional geothermal systems, and modeling suggests they could achieve levelized costs up to 50% lower than today’s systems. Mazama Energy, for example, is drilling toward superhot conditions at Newberry Volcano in Oregon (see sidebar: “Mazama Energy’s Push Toward Superhot EGS”). Meanwhile, the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy’s (ARPA-E’s) $30 million Stimulate Utilization of Plentiful Energy in Rocks Through High-Temperature Original Technologies (SUPERHOT) program, launched in 2025, seeks to address materials durability, drilling survivability, and reservoir control. Multiple assessments by the Clean Air Task Force conclude that the physics are sound, though the think tank notes commercial deployment will hinge on testing equipment under sustained superhot conditions.

Hybridization—pairing geothermal with solar thermal, photovoltaic (PV) generation, or storage—represents perhaps a more near-term opportunity. NLR modeling suggests that geothermal–solar thermal hybrids could reduce system levelized cost of energy (LCOE) by up to 50% relative to PV plus batteries, while improving overall conversion efficiency by roughly 20% versus standalone geothermal plants. Several hybrid configurations are already operating at projects in Nevada led by Ormat Technologies and Cyrq Energy.

Underground thermal energy storage, which reframes geothermal as a storage medium rather than a purely extractive resource, is another emerging theme. Technologies such as aquifer thermal energy storage, geological thermal energy storage, and borehole thermal energy storage are already widely deployed in Europe for heating and cooling. In the U.S., pilot projects in California and Texas are exploring megawatt-scale power applications, including Carnot battery concepts that store surplus electricity as subsurface heat.

Closely related is the shift toward flexible and dispatchable geothermal operations. Historically operated as baseload plants, geothermal facilities are increasingly capable of load-following, ramping, and ancillary services such as frequency regulation and spinning reserve. Empirical analysis shows that flexible geothermal dispatch could increase plant value by up to $4/MWh in markets such as California by curtailing output during low-price periods and increasing generation during high-price intervals, the NLR report notes. It also notes that more recent modeling suggests that coupling EGS with in-reservoir pressure or thermal storage could increase project energy value by 30% to 60% compared with strictly baseload operation.

Critical mineral extraction, particularly lithium from geothermal brines, has also emerged as one of the most commercially advanced non-power applications. U.S. Geological Survey assessments indicate that brines in Arkansas’s Smackover Formation and California’s Salton Sea could supply a substantial share of domestic lithium demand. At the Salton Sea, companies including Controlled Thermal Resources are already integrating geothermal generation with lithium production, seeking to turn drilling-intensive projects into diversified industrial assets. While high upfront capital costs remain a barrier, operating costs appear competitive with hard-rock mining.

Mazama Energy’s Push Toward Superhot EGSIn October 2025, Dallas, Texas–based Mazama Energy disclosed that it had reached a 331C (629F) bottomhole temperature at its enhanced geothermal system (EGS) pilot site at Newberry Volcano, Oregon (Figure 4)—marking the hottest reported operating temperature achieved in an EGS reservoir to date. While still below the superhot geothermal threshold—defined by conditions exceeding the critical point of water at 374C and 221 bar—the result is a “breakthrough” that “sets a new global benchmark for geothermal technology and marks a critical step towards delivering low-cost, carbon-free baseload power at terawatt-scale, targeting less than 5 cents/kWh,” the company said.  The pilot at Newbury, one of the largest geothermal reservoirs in the U.S., builds on decades of federally supported EGS research—beginning with Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Fenton Hill experiments and extending through Utah FORGE—but it advances into substantially hotter and more heterogeneous volcanic rock. At Newberry, Mazama interconnected a legacy injector well with a newly drilled 10,200-ft deviated production well, confirming circulation and reservoir connectivity at temperatures beyond those previously validated in U.S. EGS demonstrations. Mazama reports that drilling and completion activities maintained well integrity under ultra-high-temperature conditions, enabled by proprietary technologies combined under its MUSE (Modular Unconventional Superhot Energy) platform. These include high-temperature directional drilling, the Thermal Lattice stimulation process designed to enhance fracture connectivity, and Heat Harvester modeling tools intended to forecast long-term thermal output and well integrity. Mazama now plans to advance to a 15-MW pilot beginning in 2026, followed by a proposed 200-MW development at Newberry. Longer-term ambitions include drilling into superhot rock regimes exceeding 400C, which the company argues could deliver materially higher power density per well, reduce total well counts, and lower water use relative to conventional EGS designs. That trajectory positions Mazama as one of the most technically consequential tests underway of whether superhot EGS can transition from experimental validation to a scalable, always-available power source—particularly for industrial and data center loads seeking firm, carbon-free energy. |

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior editor.