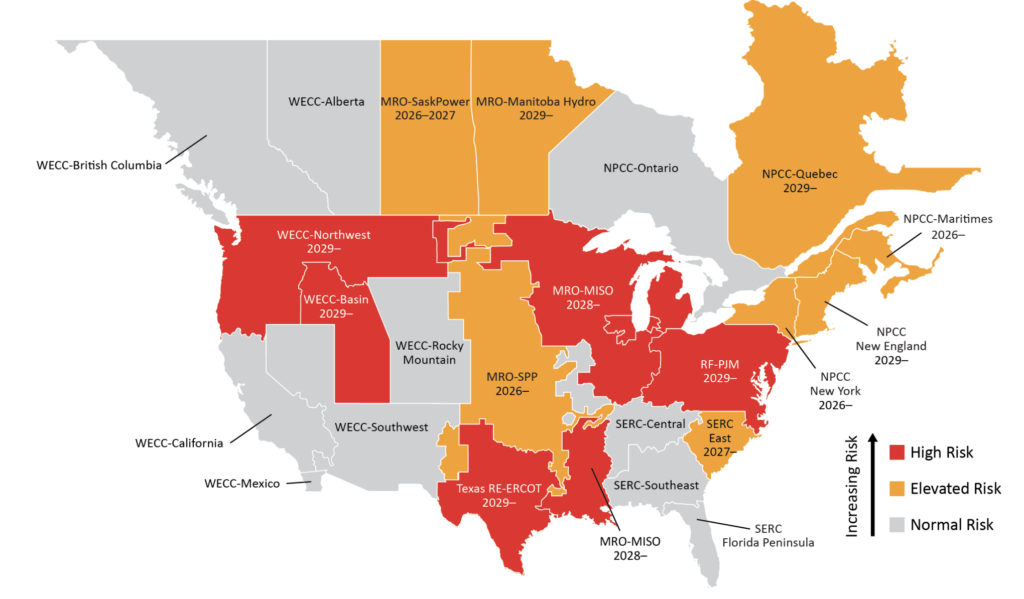

Long-time POWER readers may remember Marmaduke Surfaceblow, a fictional character whose engineering escapades were brilliantly portrayed in hundreds of stories published within POWER magazine’s pages over more than 30 years beginning in 1948. Today, the fictional series continues through Marmy’s granddaughter, Marnie, who is an engineering wiz in her own right.

____

Plant wastewater is not only an increasing environmental concern, but improper monitoring and treatment may lead to unexpected operations and maintenance problems as well.

“I have a question Mrs. Surfaceblow? How come you never got married?” asked engineering senior, Sonja Patel, one of three students in the back seat of the rental car traveling through rural Virginia.

Maya Sharma, lead field engineer for Surfaceblow & Associates International, would have face-palmed if she hadn’t been driving. “That is not an appropriate question to ask our employer, Ms. Patel.”

Frustration clearly indicated by her tone, Maya’s boss, Vice President Marnie Surfaceblow, replied, “You called me ‘Mrs.’ implying I am married, thus invalidating your question. And why ask me that anyhow? You’re too young for me.”

Failing to suppress a laugh at Marnie’s verbal riposte, Maya cleared her throat and addressed the three engineering students riding in the back of their rental car. “Did any of you read the project briefing? We are 15 minutes from the power station.”

Two of the students shrugged in embarrassment, and the third, grad student Josh Williams, lazily answered, “Yeah, I guess. It was pretty boring. Like, why do you people do so much research before going to the plant? I mean, aren’t you supposed to learn about the problem in person?”

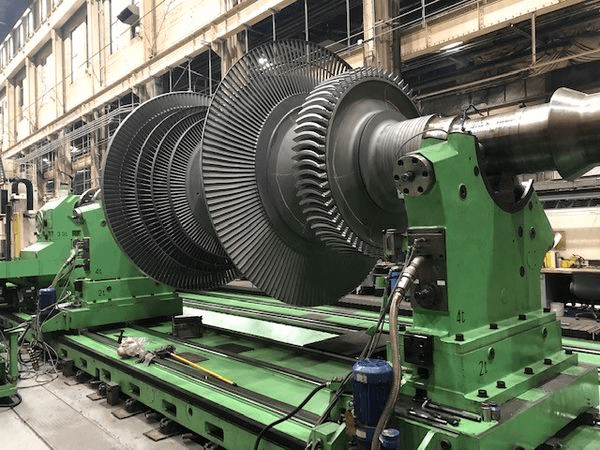

Gritting her teeth, Maya nodded toward Marnie, who after taking a deep gulp of coffee to give her strength, answered. “There are ten billion components to a Rankine-cycle power plant, and our brains can only hold so much information. You need to know the generalities of the possible problems and solutions. What if you show up and they ask you about non-destructive weld testing with iridium-192 gamma sources? What are you going to do, start looking it up on Wikipedia or asking your AI assistant about something that could kill people?”

“Wait! I thought this was a problem with like water corrosion and stuff. Is there going to be nuclear radiation?” asked a worried Sky Cothran, another engineering senior.

Before Maya could answer, Marnie shrugged exaggeratedly and replied, “Maybe. The day is still young.”

Shushing to calm the slightly panicked students, Maya quickly added, “Kindly review the job hazard assessments, and site health and safety profiles we gave you. Ms. Surfaceblow was not serious—isn’t that correct, Ms. Surfaceblow?”

“Well, the question wasn’t serious,” snapped Marnie. “Or at least I hope it wasn’t.” Turning around to face the students in the back seat, she continued, “You three don’t realize how important our profession is. We’re engineers! We crafted and we maintain the warp and weft of civilization itself! This plant supplies electricity to more than one million people, as well as the infrastructure that they need for their daily lives. We’re dealing with corrosion in their flue gas desulfurization system, which is required to operate at 98% removal efficiency under penalty of law! If we fail in our mission, then this region will be plunged into possible brownouts, or worse, just as the summer heat arrives. Not to mention more than 400 plant workers will see their jobs at risk, and maybe twice that number of workers at ancillary supporting industries. All three of you had better get serious about this, as if you were on a mission from God!”

Understanding the Situation

Marnie, Maya, and their charges sat in a group in the power plant main operations conference room, bordering the control room and separated by glass walls. A slight, balding man in his 60s wearing a button-down Oxford shirt with pocket protector was preparing to address the group. Noam Kelso had the appearance and demeanor of a NASA flight engineer attempting to save Apollo 13 (Figure 1), but he was actually the plant’s emissions controls supervisor.

|

|

1. Noam Kelso, the plant’s emissions controls supervisor, was concerned about corrosion in the wet limestone scrubber. Source: POWER |

“This corrosion in the wet limestone scrubber has been a pain in our behind for nearly two years now, and it’s only getting worse. Unit 1 is in its third scrubber outage this year, and Unit 2 probably won’t make it another month,” he said.

“I’m telling you, it’s this bad limestone we’re getting,” added Frances Meisner, the shift maintenance supervisor. “Ever since we switched to that cheap dolomite from out West, we’ve seen nothing but problems. Either that or it’s something in the coal we’re burning.” The interns dutifully took notes, occasionally whispering to Maya for clarification.

“We’ve been through this, Frances,” countered Noam. “There’s nothing wrong with the limestone that I can see, and we’re burning the same coal from the same mine, even the same seam, and we’ve analyzed the heck out of it.”

Maya looked through her notes, then commented, “Sir, your current dolomite limestone quality may contain less calcium carbonate than the limestone you historically used, but it contains twice the magnesium carbonate of your previous limestone, and the total alkaline content has increased overall. While magnesium has caused deposition in desulfurization slurry lines at some power stations, it generally does not increase corrosion.”

“So you say,” replied Frances, “but I know what I know.”

“At least it gives us a chance to clean our condenser tubes again,” added Marva Jefferson, the plant heat rejection expert. “I can’t believe we’re already up two inches in backpressure and not even hitting 90 degrees yet.”

“Indeed, and what may be going on with your condensers?” asked Marnie, taking down copious notes herself.

“You’re here to fix our scrubbers, not our condensers!” Noam blurted out in exasperation. “Our condenser tube scaling isn’t shutting us down! You’ve asked about soil erosion, our trucking companies, our wind direction, the biocides in our water, and our generation profile, but hardly anything about our scrubber! What are we paying you for?!”

Marnie Surfaceblow lacked the bellowing and bombastic demeanor of her fabled grandfather, but she knew how to convey when she was irked.

“How unfortunate,” Marnie said steadily. “You hired us, correct? Then proceed under the assumption that my questions are relevant to your situation. Yell at me again and I’ll be at the hotel in time for happy hour, and spend this trip drinking and catching Pokémon. After all, they aren’t going to catch themselves.”

“Well, I don’t see how,” grumbled Noam. “Can you help me understand what you’re thinking?”

Sighing, Marnie shook her head and replied, “So many things can impact the scrubber system. For example, your load profile tells me if you have surges of slurry flow during load changes, which may result in uneven oxidation in your reaction tank, or it can throw off your scrubber tank blowdown schedule, forcing you to rely only on reactionary blowdown to remove accumulated chlorides. And that’s just a start.”

Mulling over Marnie’s reply, Noam nodded his head. “I apologize. We’re all under a lot of pressure here. This plant has one foot in the grave, and we’re trying our best to keep that other foot from joining it.”

The Mission from ‘God’

After a refreshment break, the group reconvened. The interns talked amongst themselves and compared notes, while Maya went to examine some plant historian data. Marnie approached the interns, who snapped to attention as she walked up, and presented each of them with a USB drive.

“Each drive has professional papers pertinent to this problem,” she said. “Your missions, should you choose to accept them, are to browse those resources and try to find something that helps us solve this problem.” The students hesitated from confusion, until Marnie added, “There will be a test.”

Maya kicked off the second phase of the meeting by probing the plant staff. “Often, we find desulfurization system corrosion is highly dependent upon the materials employed, the presence of dissimilar repair metals causing galvanic corrosion, and water quality. Are any of these potential factors?” she asked.

As the maintenance supervisor attending, Frances replied, “Every part touching slurry or the gypsum waste streams is either austenitic stainless steel or polymer-coated. We spec out every repair with the same metal as original, and all repair materials must be appropriate for TIG-welding stainless. And that’s where we see the most corrosion.”

As the expert on the heat rejection systems, water quality was in Marva’s bailiwick. “We’re under a consent decree to reduce our water use to just 25% of design by 2027, so we started a program to reduce and reuse as much water as possible about three years ago. Our water comes from private wells, which we don’t get credit for but it’s cleaner than the river water onsite. We used to spend a lot of time and money fixing our debris screens and dealing with silt and sand. We send the water to a raw water pond, to our submerged drag chain slag conveyor and our mill pyrites system, and direct to the cooling towers,” she explained.

“We send the pyrites into the submerged chain conveyor, and that system conserves the water we send to it, except for some blowdown to the raw water pond,” added Noam.

“Where does the scrubber get its water from?” asked Marnie.

“We send the cooling tower blowdown there, and supplement with fresh water from the raw water pond,” Noam answered.

Maya perked up, and asked, “What quantity of the desulfurization water is from the cooling tower blowdown?”

“Not much, maybe 10, 20, 30 percent?” replied Marva.

“That’s a little bit of a spread,” muttered Marnie. “Can you tell me more about this limestone you think may be the problem, Frances?”

Put on the spot, the maintenance supervisor hesitated, but then replied, “Ever since commissioning we used good quality limestone from a quarry just down the road. Then the costs started to go way up, and ambient dust regulations forced the mine to shut down. That’s when we found out we’d been living a charmed life, because all the other limestone in the area was three times what we’d been paying for it. So, we searched around and found this dolomite. Right away I hated it, it didn’t crush as well in our ball mills, it’s got sand and other stuff in it, so it’s hard to grind really fine.”

Marnie was pleasantly surprised as her intern Sonja looked up from her laptop and cautiously raised her hand. Curious, Noam smiled and asked, “Yes, young lady, do you have a question?”

Clearing her throat and glancing at her computer once, Sonja asked “Um, excuse me, sir, I was wondering, what kind of cleanup do you do to the scrubber water before you use it? I mean, could there be something in there maybe?”

“Good question,” replied Noam. “We don’t treat it as well as boiler water—that water is really clean. For scrubber water, we focus on three things: filtering out silt and sand, using biocides to kill bacteria—some really like eating sulfur in the slurry and cause all sorts of problems—but the most important thing we do is try to clean out the chlorides and other halogens.”

The surprises continued as Sky raised her hand. Intrigued, Noam asked, “Do you have a question too?”

Reading from her laptop screen briefly, Sky cleared her throat and asked, “You said your dolorous limestone wasn’t as good as your limestone you used to get, could there be something in it that’s causing problems?”

“You mean dolomite limestone,” Noam gently corrected, “and we’ve looked at it too. I mean, it’s a rock, and the only thing I see of significance is the magnesium is pretty high in it. It’s about 20 times as high as what we used to get.”

Marnie looked to see if Josh had a question, but the young man was flipping through notes and the project briefing looking for something. As the questions had effectively run out, Marnie asked for five copies of the plant site map, and after receiving them she passed one out to each of her team. “Right!” she announced suddenly. “Time to search for treasure!”

Finding Treasure

Marnie’s idea of searching for treasure was to walk Maya and the interns around the site, with Noam and Marva escorting the group. They inspected various equipment items, occasionally taking samples of limestone, coal, ash, water, and soil. Upon Marva’s urging to view the condenser tubes, exposed for cleaning as part of the Unit 1 outage, Maya noted something and called the students over. “See? Each tube has thousands of tiny corrosion pits, forming anchors for scaling to accumulate. This may also point to a possible culprit.” Marnie nodded with approval and whispered “good catch” to her lead engineer.

As Marva and Noam had to attend another meeting and could no longer escort through the plant proper, Marnie led the group through the early afternoon warmth toward the raw water pond. As they walked through the long grass toward the pond, Josh caught up with Marnie and said, “Um, ma’am, I wanted to check something, I think it might be important.”

“Great job!” said Marnie with genuine enthusiasm. “Always suspect anything that could be important. What is it?”

Checking his notes, Josh asked, “Um, I wrote down that Maya—Ms. Sharma—said the magnesium in their limestone was twice as high as normal, but then Noam, he said it was like 20 times as high. Which is it?”

“How curious, said Alice!” replied Marnie enthusiastically. “You should dig into that to find out what is two and what is 20.” Semi-confused, Josh nodded and wrote Marnie’s reply in his notes.

When they arrived at the raw water pond, Marnie walked along the bank pointing out items from her site map. “Here is where the water comes from the wells, and here is where the blowdown comes from the cooling towers, and here is the intake for the scrubber water going to its treatment area. Anyone see anything interesting?”

|

|

2. Maya noticed the crawfish in the raw water pond were an unusual black color. Source: POWER |

The group walked around the shore of the pond, poking at the ground, surveying the water, and generally looking confused. “I see many crustaceans, ma’am, and they are an unusual color,” Maya observed. The interns quickly gathered around her, as she stood near a small colony of crawfish (Figure 2).

“Let me guess, are they black?” asked Marnie idly. Maya nodded. “I thought so,” Marnie continued. “Hey, kiddos, look at this over here by the cooling tower blowdown pipe—what do you think this could be?”

As everyone arrived, they noticed the ground around the pipe, as well as the bottom of the pond, was discolored reddish black. Marnie asked Sky to carefully collect some samples of the stained areas for analysis. Suddenly, Sky gasped and jumped back. “I know what this is—this dark red, it’s thorium oxide! This is a radioactive waste pond!” she exclaimed.

“When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not unicorns,” Marnie instructed. Removing a small device from her pocket, she handed it to Sky and said, “Thorium oxide is orange-yellow, but here’s a Geiger counter, why don’t you see what it tells you?”

After Marnie instructed her on Geiger counter use, Sky was relieved to find no signs of a pending Chernobyl at the raw water pond. Marnie passed out lab jars for the interns to take water samples, and she and Maya performed pH testing on some of them.

It was Josh who noticed something troublesome. He turned to Maya and asked, “So, like, is it good that the intake for the scrubber water is right by the pipe coming from the cooling towers? It looks like it’ll suck that blowdown right up.” Maya placed a hand on Josh’s shoulder. “A very astute observation. I concur.”

After consulting with Maya in low tones for a few minutes, Marnie led the interns back to the engineering building, while Maya played shepherdess again.

Mn Vs. Mg: A Clear Difference

After a quick meeting outside the door, Marnie and company entered the conference room and walked to the head of the table to present their findings. “Maya and I think we’ve got this figured out, but we’d like our interns to present our team’s findings to gain some experience,” Marnie began. “OK, kiddos, that’s your cue!”

The interns were nervous, but smiles from Maya and Marnie gave them confidence. Sonja was first. “What’s causing problems with your scrubber and cooling towers is probably manganese. The well water analyses have much higher manganese than the river water analyses. Um, this gets concentrated in your cooling towers, and caused the corrosion and scale in your condenser. There are tiny holes in the metal meaning this is likely,” she said.

Then it was Sky’s turn, and she began with much more gusto. “When you blow the cooling towers down, the manganese goes to your raw water pond. Manganese is hurting the wildlife at your pond, and making stains on plants and animals that are definitely not radioactive.” There was a slight murmuring in the room, and Marnie snorted a laugh, then waved for Sky to continue. “Then Josh saw that your pipe from the cooling towers empties not far from the intake for your scrubbers, and the water with, um, high manganese is going right to the scrubbers. Thank you!”

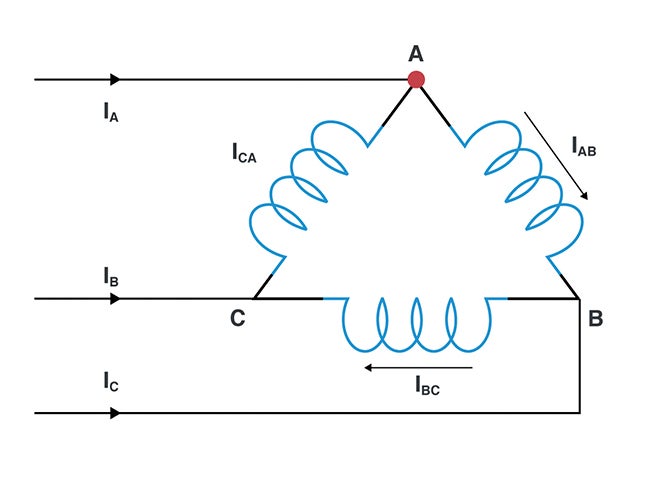

Josh was up next. “So, Mr. Kelso, Noam, um, said the magnesium in your dolorous—I mean, dolomite—was 20 times higher than normal, but Ms. Sharma said it was twice as high, so I looked at your lab sheets and it was manganese that’s about 20 times higher. Maybe you got confused between the ‘Mg’ and ‘Mn’ and thought one was the other? Anyhow, one reason the manganese is causing so much trouble in your scrubber is it attacks stainless steels more than other steels, so your stainless steel protects you against some corrosion, but not manganese so much,” Josh explained.

Marnie nodded to Maya to bring it on home, so Maya stepped forward and addressed the group. “Thankfully, this problem has easy solutions you may choose from. First, there are many methods to treat manganese in your well water to keep it from building up quickly—halogens, peroxides, and other solutions are not difficult to employ—I recommend peroxides for your situation,” she said. “Next, you must find a source for lower-manganese limestone. We researched only a few minutes but found several vendors offering better limestone at a small incremental cost. Finally, you must re-locate your cooling tower blowdown piping, even to the other side of the raw water pond, to allow the manganese to dilute.”

“You may be required to treat the manganese at the pond as well,” added Marnie. “I mean, it’s concentrated enough to turn your local crawfish black, and unlike blackened redfish, which is a true delicacy, blacked crawfish just tastes … bad. Trust me.”

—Una Nowling, PE is an adjunct professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.