After months of controversy, Australia’s federal government in October dumped its consideration of a clean energy target (CET) that sought to slash the country’s electricity emissions of carbon dioxide by 28% in 2030, compared to 2005 levels, essentially refraining from extending the nation’s renewable energy target beyond 2020. It turned its focus instead to a “national energy guarantee,” which imposes new reliability and emission reduction guarantees on energy retailers and some large energy users.

The about-turn by the government led by Malcolm Turnbull is widely seen as an attempt to unify Australia on its messy energy and climate change politics. Over the past decade, the federal government has seriously debated a number of measures, including the proposed Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, the introduction and repeal of the carbon price, and renewable energy targets. State governments, meanwhile, have for years floated their own measures.

But for many industry observers, because the proposed national energy guarantee lacks adequate detail and requires endorsement by lawmakers on both the federal and state levels, it may end up in the pile of scrapped efforts that sought consensus between the country’s energy security and environmental needs.

Others contend that because the guarantee policy imposes a legally binding cap on carbon emissions from the power sector, it would serve as a major reform. The national energy guarantee also obliges retailers to meet a share of their load with flexible and dispatchable power resources; retailers would need to factor in the set emissions level when entering into contracts, or face market deregistration. Proponents of the measure also say that because it provides some semblance of a stable policy, it could encourage power companies to invest in more capacity.

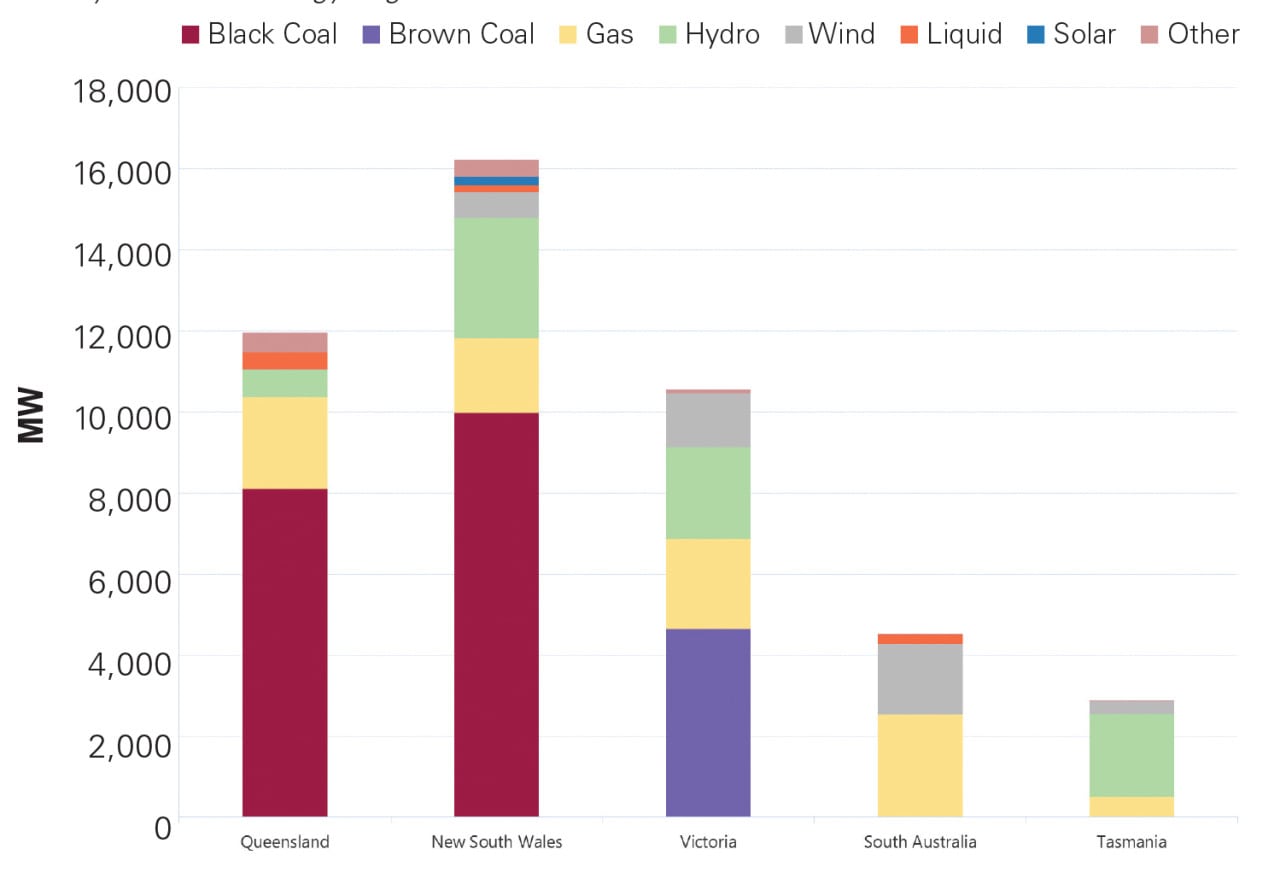

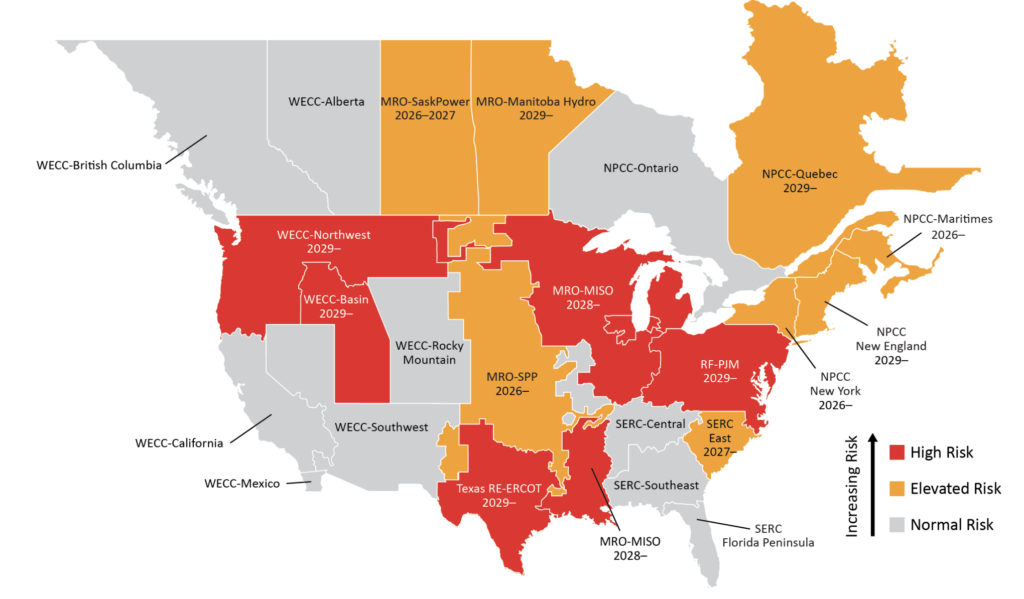

Australia faces real reliability concerns, experts note. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) in a September 2017 “Electricity Statement of Opportunities” report warned that the national electricity market, whose total capacity amounts to about 47 GW, lost 1.1 GW over the past year. The loss factors in retirement of the 1.6-GW coal-fired Hazelwood Power Station, which was taken offline in March due to “difficult market conditions.” Over the past year, the market added 465 MW—all wind (Figure 6). AEMO also starkly cautioned that as a result of “rapidly changing dynamics” of the power system, “reserves have reduced to the extent that there is heightened risk of significant unserved energy over the next 10 years, compared with recent levels.”

For now, the proposed national energy guarantee policy is set to be finalized in 2018. The reliability guarantee is expected to become effective by the end of 2019 followed by the emissions guarantee by the end of 2020.

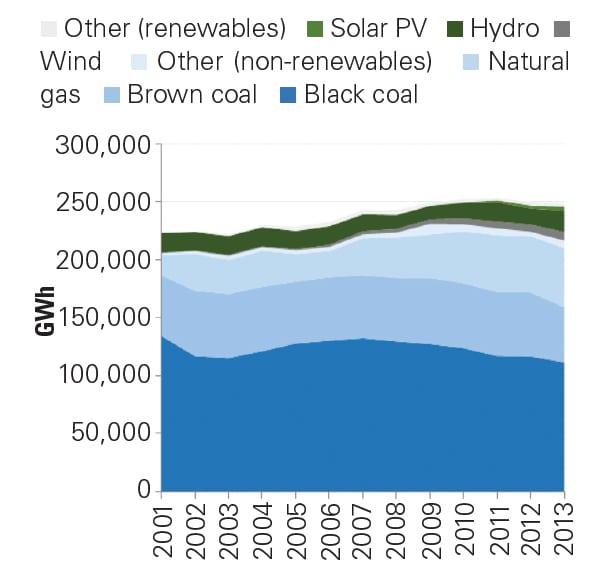

Gripes about the government’s sudden dump of the CET are certain to persist, however. The CET was favored by Australia’s chief scientist, Alan Finkel, who modeled the target in a much-anticipated report released this June. While the target was proposed to replace the existing renewable energy target in 2020, it was much lower than the reductions of 60% some experts said are necessary for Australia to meet carbon targets to which it has committed under the Paris climate agreement. Finkel’s report essentially concluded that setting a target was better for Australia’s emissions goals when compared to an emissions intensity trading scheme—which was broadly supported by experts and industry stakeholders. While the CET didn’t penalize “high emissions generators”—and it still allowed for power generation from brown coal—modeling in the report indicated that by 2030, coal power’s share would drop from a projected 57% without any policy changes to 53% under the CET, while gas’ share would fall from 8% to 5%. Renewable power’s share—the bulk from wind—would soar to 17%.

The report, however, also underscored energy security and reliability priorities, recommending that aging power plants provide energy regulators with at least three years’ notice before they shut down permanently. All new generators, meanwhile, would be required to meet technical requirements to complement a grid characterized by fast frequency response, and it set minimum levels of inertial response for each power market to ensure it could better withstand disruptions like generator outages or failures.

The measure was predictably opposed by former prime minister Tony Abbott, who in 2013 pushed to scrap what he said was a “punitive” carbon levy and replace it with a so-called “Direct Action Plan.” (For more on the history of Australia’s intricate carbon policy, see “Australia’s Carbon Policy Predicament” in POWER’s April 2014 issue). Current Prime Minister Turnbull, who heads up the center right–leaning Liberal-National Coalition, had lauded the CET for its numerous “very strong virtues,” including its technology neutral and administratively fair attributes.

In mid-October, however, Turnbull said the national energy guarantee was a better way to gain consensus, predicting states would ultimately sign up to it because Australians are “sick of the climate wars.” Yet at least one state, South Australia, whose premier Jay Weatherhill is from the left-leaning Labor party, has railed strongly against the measure because it cuts renewable energy targets and promotes coal. Weatherhill said that if Turnbull was serious about the policy, states should have been included in the process as they were in the Finkel review.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor.