The Trump administration has revived the discussion of using Yucca Mountain in Nevada as a repository for the nation’s nuclear waste. Nevada officials remain opposed to the idea of putting spent nuclear fuel in long-term storage at a site about 100 miles from Las Vegas.

But while a bill to resurrect Yucca Mountain as a storage site moves through Congress, other groups have stepped forward with plans to site, build, and operate nuclear waste storage and disposal facilities in areas including Texas and New Mexico. Those plans have reignited the debate about what the U.S. should do with its nuclear waste, along with the discussion of whether the federal government or the individual states should take the lead in developing long-term storage plans.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) says at least 12 U.S. reactors are committed to closing over the next five years, joining the more than 20 reactors shuttered over the past 10 years across the country. That’s lot of spent nuclear fuel, in multiple locations, in need of safe storage, whether at an interim site or at a facility designed for long-term storage.

“If we can start moving fuel to an interim storage site, we’re making progress,” said Ward Sproat, former director of the Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), part of a panel discussing consolidated interim storage solutions for nuclear waste at ExchangeMonitor’s RadWaste Summit at the Green Valley Resort in Henderson, Nevada, on September 5. ExchangeMonitor is a sister company of POWER magazine. “Interim storage has been done before. We have a bunch of interim storage sites around the country. Getting the license isn’t the hard part, it’s getting to the point of actually moving the nuclear waste.”

“The safety record of our nuclear transportation industry is the envy of the world,” said Eric Knox, vice president of Strategic Development, Nuclear & Environment, Management Services Group at AECOM. Knox moderated Wednesday’s panel. He echoed Sproat in saying transportation concerns have been a rallying point for those opposed to storage of nuclear waste, often using the phrase “mobile Chernobyl” in their opposition.

Interim Storage Sites in Development

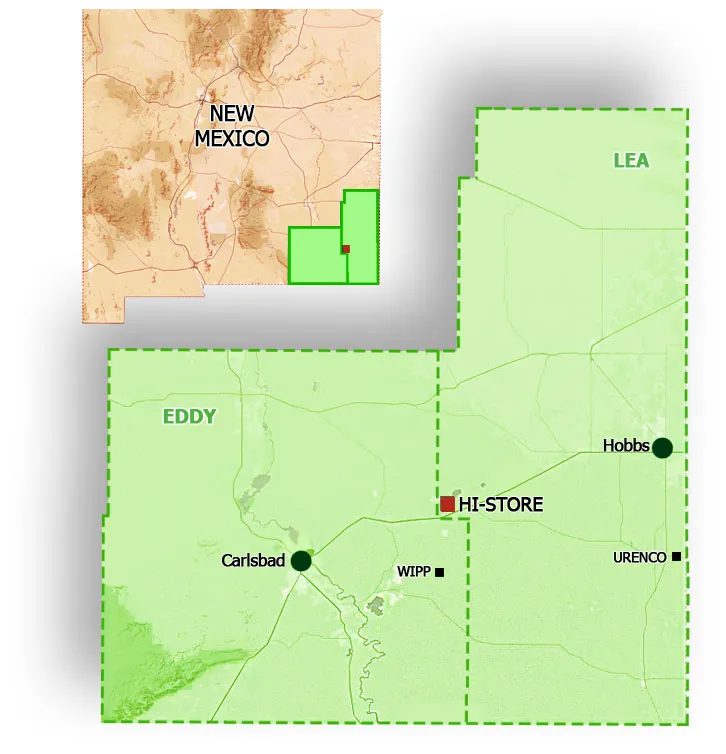

Two members of Wednesday’s panel represented companies developing interim storage sites. Interim Storage Partners (ISP), a joint venture of Orano USA and Waste Control Specialists (WCS), is pursuing a license for a consolidated interim storage facility (CISF) for used nuclear fuel at an existing WCS disposal site in Andrews County, Texas. Holtec International, which has been acquiring nuclear plants that have closed or are scheduled to close in order to carry out their decommissioning, is developing a CISF in southeastern New Mexico, in a remote area between Carlsbad and Hobbs.

Jeffery Isakson, CEO of ISP, said Texas lawmakers have repeatedly supported radioactive waste disposal operations in the state. The NRC on Wednesday said it would resume it review of the ISP license application for the Texas facility, which had been suspended after being originally submitted in April 2016.

“Environmental impacts have been extensively analyzed in the region,” Isakson said, adding the site has rail lines available that can handle loads including canisters of spent nuclear fuel. Other infrastructure for the site also is in place, and WCS opened a visitors’ center in Andrews County, Texas, in June 2018.

Joy Russell, vice president of corporate business development and chief communications officer for Holtec, said her company formed a business unit—Comprehensive Decommissioning International—in a 2018 joint venture with SNC-Lavalin after SNC-Lavalin in 2017 acquired Atkins, a nuclear waste solutions company. Russell said the New Mexico site encompasses about 1,000 acres, with “about 500 acres being used to build the facility.” Russell said the site, known as HI-STORE CIS, would use the company’s HI-STORM UMAX technology, which stores loaded canisters of nuclear waste in a subterranean configuration.

Russell said her group has a public-private partnership with the Eddy Lee Energy Alliance, representing Eddy and Lee counties in New Mexico, for the project, which she said has support from both local and state officials.

“We’re doing educational outreach in New Mexico,” said Russell. “We do township meetings, where we testify before the mayor and town council. We meet one-on-one with candidates. We had to start with the basics. What people think of when they hear nuclear fuel, they think of the fuel you put in your car, and how that could leak into the ground. We have to educate people on what [nuclear] fuel is. We focus on safety, security, and technology.”

Russell agreed that public concerns centers on the transport of nuclear waste. “The number-one thing I hear, all the time, about consolidated interim storage is transportation.” Holtec also has its license application before the NRC for review; Russell said it expect the agency will complete its review in July 2020, putting the New Mexico site on a timeline to receive its first shipment of spent fuel in 2023.

Revisiting Yucca Mountain

Congress first chose Yucca Mountain as a storage site for nuclear waste in 1987. Years of research into the site followed; estimates are that $15 billion was spent on the project. Sproat noted his efforts on licensing for Yucca Mountain before his retirement from the DOE, with a license application submitted to the NRC in 2008. The Obama administration ended funding for the project and halted the licensing process in 2009.

Meanwhile, the Nuclear Waste Fund (NWF), which collected money from the states to finance waste storage projects, was ordered by a federal court in late 2013 to stop collecting that money until the federal government made provisions for collecting that waste.

“I’m a little frustrated,” Sproat said. “After putting in all that effort for that license application, here we are 10 years later with little to show for it.”

President Trump earlier this year earmarked $120 million to restart the Yucca Mountain licensing process in his fiscal year 2019 budget. Sproat is not optimistic waste will ever be stored at Yucca, citing both timing and political issues.

“Assumptions that were made back in 2008, that the Nuclear Waste Fund was viable to operate Yucca Mountain, those are no longer valid,” he said. “All of those assumptions are out the window. There’s not enough money there at this stage of the game to operate and fund it.”

He continued: “Bottom line on Yucca is, I think we can defend that license application, but the Department of Energy needs to be a willing applicant to do that. But the time frames to be able to do that are getting shorter and shorter. There are two dynamics that run through all of these topics. Politics and time.”

Sproat said any application for a long-term storage site would require submitting an integrated design, both above and below ground of the proposed facility, before anything is submitted to the NRC. “You are easily talking 30-plus years to make that happen,” he said. “Time is not on your side in any of these [scenarios]. Political leaders change. The people you talked to get consent at the beginning, they won’t be there later on.”

That’s why CISF sites are growing in importance. “Private industry is stepping up to make things happen,” said Sproat.

Both Isakson and Russell reiterated that local support is strong for their projects, though they recognize there are hurdles. Neither wanted to discuss their companies’ business models, beyond their optimism the NRC will approve their applications.

“The funding issue is the crux of this,” Isakson said. “We’re going to get the license for the facility and we’re going to ship fuel there, if there is funding to do that.”

As for the NWF, William Boyle, director of the Office of Used Nuclear Fuel Disposition Research & Development, Fuel Cycle Technologies, asked about that $120 million in the fiscal 2019 budget, said the answer to the question of whether the DOE is continuing to fund the NWF is simple: “No.”

“We don’t spend the president’s budget,” Boyle said, as he presented an update on the efforts of the DOE’s Office of Nuclear Energy regarding spent nuclear fuel. “We spend the money that Congress appropriates.”

—Darrell Proctor is a POWER associate editor (@DarrellProctor1, @POWERmagazine).