Ausgrid, the state-owned electricity distribution giant that delivers power to 1.8 million customers across Sydney and beyond, has proposed a “Community Power Network” (CPN) that could shatter a century-old regulatory boundary by allowing the monopoly network operator to directly own solar panels and batteries, sell electricity in competitive wholesale markets, and redistribute the profits to local communities.

The A$187 million proposal represents an audacious challenge to Australia’s carefully constructed market architecture, where regulated monopoly networks (distribution utilities) have been strictly separated from competitive generation and retail since deregulation began in the 1990s. As the country’s largest electricity distributor, covering 22,275 square kilometres from the Hunter Valley to Sydney’s industrial heartland, Ausgrid’s move could rewrite the fundamental rules governing how power flows—and who profits—in Australia’s $15-billion electricity industry.

Testing Community Power at Scale

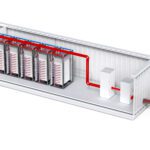

The company has set out to trial the new program, which is now under public consultation until Sept. 16, that would see Ausgrid install 70 MW of solar panels and 130 MWh of batteries across two Sydney suburbs: the industrial hub of Mascot-Botany and the residential area of Charmhaven on the Central Coast. The trial seeks to serve about 32,000 households, including renters, apartment dwellers, and low-income residents who are traditionally excluded from rooftop solar benefits. More significantly, it will use shared local batteries to store excess solar energy generated by participating households and community assets, then orchestrate the use of this stored energy to reduce peak demand, stabilize local networks, and support the broader grid.

A key facet is that it will redistribute the economic benefits—including a projected $22.9-million dividend pool over five years—back to community members through bill reductions and direct payments. The approach is designed to address energy equity gaps by enabling those who cannot afford or access individual solar installations to participate in the benefits of renewable energy, leveraging a managed local energy ecosystem that combines distributed generation, shared storage, and network optimization to lower costs, improve reliability, and accelerate decarbonization efforts in targeted communities, Ausgrid says.

“We’re taking two suburbs within our network and we’re looking at the area underneath the zone substation,” explained Ausgrid CEO Marc England to the SwitchedOn Australia podcast on Aug. 18, 2025. “We picked the two suburbs deliberately because they’re different profiles. Charmhaven on the central coast is much more residential than the other suburb which is down at Botany which has got a mixture of residential, social housing. It’s got a high proportion of renters and also a lot of warehouses.”

The pilot specifically targets energy equity gaps that plague Australia’s renewable transition, Ausgrid notes. While one-third of Australian homes have rooftop solar, two-thirds remain excluded—notably the 50% of Ausgrid customers who rent and can’t install their own systems, it says. By coordinating warehouse-scale solar installations with community-scale storage, the model promises to unlock “enough untapped roof space to supply the whole of Ausgrid’s annual demand if the power could just be produced and then distributed to the right times of day.”

England cites University of New South Wales research that suggests the program could unlock “enough untapped roof space to supply the whole of Ausgrid’s annual demand if the power could just be produced and then distributed to the right times of day.” In some suburbs, he claims, “it could be 100%, but let’s say 80% to 85% of the demand for residential and small and medium enterprises was met locally.”

Energy Equity in Focus

Ausgrid will run reverse auctions where solar installers bid to supply power at the lowest cost, with the network operator offering feed-in tariffs “above the feeding tariff that most surplus solar is getting from the wholesale market or from their retailer today.” Commercial property owners can earn up to A$440,000 profit per megawatt over the asset’s 16-year lifespan, while surplus power flows into Ausgrid-owned batteries strategically placed throughout the suburbs. The stored energy gets redistributed during evening peak hours, establishing what England calls a “value pool” that benefits every customer in the trial areas, including renters, apartment dwellers, social housing residents, and homeowners alike.

“Whether you’re a homeowner, whether you’re a renter, whether you live in an apartment block, doesn’t really matter. You’ll just receive a discount on your bill as a result of the value created in your community,” England suggests. Modeling suggests a A$200 annual savings per household, he said, though he acknowledges “lots of assumptions in that and that’s what will be tested through the pilot.”

The proposal requires unprecedented regulatory waivers from “ring-fencing” rules—legal barriers designed to prevent network monopolies from dominating competitive electricity markets. The rules exist because distribution companies like Ausgrid enjoy guaranteed revenues, captive customers, and regulatory backing that private competitors cannot match.

“Our industry and its current structures were designed about 30, 35 years ago in the early ’90s,” England explained. “The regulatory boundaries of that mean Ausgrid today couldn’t do this pilot if we just chose to do it. We have to get permission to do it.” The Australian Energy Regulator’s (AER’s) sandbox mechanism provides one pathway, he noted. “We get to go and play in the sandbox if they approve it,” he said. “It allows us to break the current boundaries of what we’re allowed to do in order to test those hypotheses.”

Balancing Innovation with Reliability

For now, however, Ausgrid’s May 12-submitted trial waiver is posing a substantial quandary for the AER, the federal regulator tasked with balancing innovation against market integrity. Ausgrid expects a decision in late 2025, which would trigger spatial energy planning and partnership contracts, followed by mid-2026 construction and the first wave of solar and storage assets operational by mid-2027. The pilot will run through 2031, with dividend payments beginning mid-2028 and regular reviews to determine whether the model should be modified, reverted, or scaled based on outcomes.

The timing appears particularly sensitive, given Australia’s ongoing struggle to balance reliability and affordability while racing toward its ambitious clean energy goals. Renewables supplied 43% of generation in 2025, and its target of 82% by 2030 will be an uphill climb amid soaring household power bills (slated to soar nearly 10% in New South Wales), grid connection bottlenecks, and warnings of potential blackouts as coal plants retire faster than new renewable projects can come online. While the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO’s) Aug. 20–released 2025 Electricity Statement of Opportunities suggested reliability outlooks have improved (given a pipeline of 50 GW of prospective generation, storage, and transmission projects), it warned that the system remains critically dependent on those investments arriving “on time and in full.” AEMO CEO Daniel Westerman has described the 10-year pipeline as “healthy,” but points to a looming 28% surge in demand, driven by data centers, electrification, and industry, that will coincide with 11 GW of coal retirements. Even with record additions of 4.4 GW last year and expectations of 5 to 10 GW annually through 2030, the report flags that delays, drought, or outages could reopen reliability gaps.

England recognizes that the program’s fundamental nature is “bold.” Community solar is not new. Renewable energy, well-suited to “decentralized deployment and local ownership” has long held the potential to “democratize how energy is consumed and produced,” international policy network REN21 in a 2024 report, which argues local ownership models are key to transforming energy systems into more inclusive and resilient networks. REN21 points to examples in Brazil—such as RevoluSolar’s cooperative-based “community solar” project—and highlights successful programs in the U.S, Canada, and Australia, where models like solar cooperatives, shared solar gardens, and community-owned installations have delivered local economic and social benefits through widespread community participation and ownership.

Ausgrid’s Community Power Network, however, is distinctive given its distribution grid scope, its integration of local batteries, and the reverse auction process, which allows commercial property owners to set their own feed-in rates while surplus solar is pooled centrally and savings, after battery costs, are shared across all network participants regardless of whether their property hosts solar.

Global Models and Market Tensions

A parallel international example, perhaps, comes from Iberdrola’s 2019-launched Solar Communities program (Figure 1), which recognizes that more than two-thirds of Spain’s population “lives in high-rise buildings.” Iberdrola’s program has achieved remarkable scale, reaching 1,000 solar communities by April 2025 and serving more than 100,000 families across Spain. “In Spain, Iberdrola’s Solar Communities program allows residents to access solar from shared installations on public or commercial rooftops within about two kilometres of their homes. Participants sign up online and immediately share in the output, with savings of around 30% reported across more than 1,000 communities serving over 100,000 households,” Monaghan explained. The Iberdrola program operates through two models: customer-owned installations where residents collectively invest, and Iberdrola-investment communities where the company owns the panels and allows digital subscription. Madrid leads with 170 installations, followed by Valencia with 148, while Extremadura hosts over 19,000 participating families.

|

|

1. The Palmeral solar community in Alicante, Community of Valencia. Iberdrola España’s network of more than 1,000 shared solar communities now supplies renewable energy to more than 100,000 households across Spain, cutting bills by up to 30% and avoiding 640 metric tons of carbon dioxide per site over 30 years. Courtesy: Iberdrola |

“The Spanish model is notable for its simplicity and consumer-facing design. It demonstrates that shared renewables can be delivered at scale, but it is led by a retailer operating within competitive markets, not by a regulated distribution business,” Monagan noted. Ausgrid’s proposal, in contrast, risks entrenching network-led models at the expense of competitive market approaches, he argued. “What this proposal risks is the creation of autonomous path dependency, where the future development and regulation of CPNs is influenced by the pre-existing regulatory frameworks and practices of the systems they are built upon, rather than a purely optimal, autonomous approach to future development such as Iberdrola’s model”. Monaghan also expressed skepticism about the absence of “clear data on failed tenders, rejected proposals, or unmet demand in specific locations.” Assurances about provider access are “not relevant,” because the trial’s structure and regulatory waiver itself “could risk crowding out competitive providers,” which could prompt “blurring the lines that underpin the market’s design,” he stressed.

According to Ausgrid’s England, the Community Power Network’s economic case centers on network efficiency. “We estimate in these zones we’re going to test, the community power network, where we could reduce the peak by 30%,” he said. “If we can reduce the peak in those areas by 30%, guess what you can do? You could add more demand. You could add a data center.”

England suggests networks are the “missing middle” in energy debates. “There’s a lot of discussion around transmission and large-scale wind farms and large-scale solar farms. At the other end of the spectrum, there’s also a lot of discussion around community energy resources, things in homes,” he says. “Across the 13 distributors in Australia, of which we’re one, we see opportunities that are being missed.” Ultimately, solutions will require a rethinking traditional boundaries, he suggested. “This is not a 50-meter race across a pool. This is an ocean race. And sometimes the quickest way to the finish might mean you have to not go in a straight line.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).