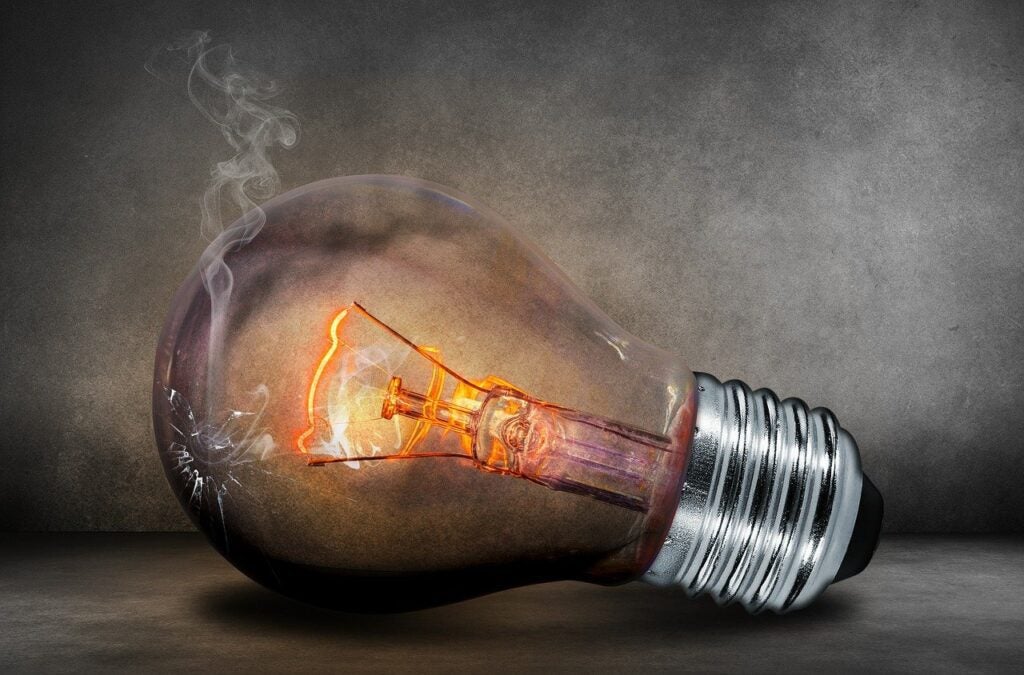

Back-to-back transmission grid failures in India plunged nearly 670 million people—roughly 10% of the world’s population—into darkness on Monday and Tuesday, paralyzing transport networks and crippling the country’s economic ambitions. Larger than both the August 2003 North American blackout and the March 1999 southern Brazil blackout, the unprecedented Indian grid failures are among the world’s worst.

Trouble began on Monday, July 30, as excessive power demand and a chronic supply shortfall was exacerbated by less-than-normal rainfall from the weak summer monsoon that strained the country’s hydroelectric power supply. India relies on hydropower for 20% (38,990 MW) of its total generating capacity. The Northern Grid, which serves more than 300 million people across nine states, including the nation’s capital New Dehli, tripped at around 2:30 a.m.

Power was restored about 12 hours later, only to fail worse the next day. On Tuesday, the chaos spread as the Northern, Eastern, and Northeastern grids collapsed, slashing power to more than 60% of the country’s population in an area that stretched 2,000 miles from Imphal in the east to Jaisalmer in the west. The Western and Southern grids were unaffected.

According to an initial investigation by state-owned grid operator PowerGrid’s subsidiary Power Systems Operation Co. Ltd. (PoSOCO), a prior incident "of heavy power flow" had led to a "near-miss" situation earlier, at about 3:10 p.m. on Sunday. The disturbances on Monday and Tuesday were primarily set off by "heavy power flow," exceeding 1,000 MW on the 400 kV Bina- Gwalior-Agra single circuit section, it said.

Power was restored in 20 states by 9:30 a.m. on Wednesday, but experts warned that the country faced more crippling blackouts owing to its fragile and overstretched electricity network. At the root of the problem is that India is facing a chronic supply deficit that has recently been worsened by the closures of nearly 30% of India’s grid-connected generation capacity, owing to fuel scarcity, plant maintenance, and technical faults.

An Enduring Deficit

Fossil fuels account for about 65% of the country’s total installed capacity (coal capacity for about 56%, natural gas, 9% and oil, about 1%), but the country has been grappling with an unprecedented coal shortage that has forced privately owned and money-strapped state-owned coal-fired power plants alike to rely on expensive imports from Indonesia and South Africa to replenish woefully inadequate stocks. Natural gas is also in short supply in India, forcing gas power plants to operate at load factors of around 58% to 60%.

Compounding the country’s deficit dilemma is a spike in power demand. Surging electricity demand from India’s growing population of 1.2 billion people has strained the country’s inadequate power supply and distribution infrastructure, resulting in an overall average peaking shortage of about 12%.

Meanwhile, to support the country’s expanding $1.7 trillion economy, India’s government has embarked on plans for massive capacity additions, seeking to add 150 GW to 175 GW over the next decade. But experts say a variety of issues—from fuel constraints, regulatory and tariff issues, shortages of skilled manpower and construction equipment, and infrastructure issues, to bureaucratic delays in obtaining clearances and permits—will limit the country’s ambitious capacity additions.

A Rickety Framework

Overarching all these challenges is a rickety institutional framework. A host of energy policies were adopted after independence to serve the socioeconomic priority of development, but these have instead "encouraged and sustained many inefficiencies in the use and production of energy," as India’s Planning Commission acknowledges.

Today, the central and state governments together own and operate about 73% of India’s installed power capacity, though the share of privately owned capacity is increasing. According to some experts, this has resulted in underinvestment in all aspects of the electricity system—generation, transmission, and distribution. Another aspect is that power generators are unable to adjust power prices—developed at state-level where governors have kept consumer tariffs artificially low—in line with raised input costs.

Driven by populist politics, state electricity boards pushed for cheap electricity for agriculture in the late 1970s to stimulate India’s Green Revolution. In the 1980s, by raising tariffs on industrial consumers, farmers in several states began receiving power for free or at flat rates. Despite reforms, many state electricity boards are, as a result, cash-strapped, but governors of farming states have declined to raise tariffs or relinquish subsidized power, calling these issues "politically sensitive."

Meanwhile, as the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC), India’s federal power regulator, appointed a three-member committee to probe the causes behind this week’s failures, it reportedly suggested that the underlying reason for the blackouts was "excess electricity withdrawals" by a few states, including Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Haryana, despite several warnings from grid-operating entities.

India’s states typically arrange to buy electricity a day in advance, but some states withdraw more power than was arranged, even though they incur penalties from the central electricity regulator. Criticism that penalties are too low to prevent states from overdrawing power have been allayed by concerns that cash-strapped state energy boards—some that had to be bailed out by the federal government earlier in July—won’t be able to afford them.

“Around 3,000 MW of power has been overdrawn from the eastern grid. Strict action will be taken against the states indulging in overdrawal,” Power Minister Sushilkumar Shinde told reporters on Tuesday, just hours before a high-profile cabinet reshuffle that put him in charge of the Home Ministry.

Shinde was replaced by former Minister of Corporate Affairs M. Veerappa Moily, who said as he took on the mess that has deeply embarrassed the Indian government: “I don’t think one can have a blame game between the state and the center.”

Sources: POWERnews, POWER, CERC, Times of India

—Sonal Patel, Senior Writer (@POWERmagazine)