Utilities have sometimes lagged behind other sectors in applying advanced management techniques, but that may be changing as the industry recognizes the importance of lean, efficient supply chains.

There may be few things about power plant management less exciting than its supply chains. But few things can gum up a plant’s operations more completely than mismanaging supplier relationships, parts sourcing, and inventory.

Supply chain management has undergone substantial evolution in the past few decades along with other changes in management philosophy that began in the 1980s. Procurement, once viewed as a low-level clerical function, is now recognized as a key specialty in any organization’s operations.

But the field is not standing still. Utility supply chain experts have recognized that there is still plenty of room for improvement, and that while some utilities and generators are leading the way on managing lean, efficient, smooth-running supply chains, many others still have substantial savings and efficiencies to capture.

Speakers at the 12th Platts Utility Supply Chain Management Conference held Jan. 20–22 in San Diego generally agreed that supply chain management starts with aligning internal elements of the utility for optimal efficiency, but attention needs to be devoted all the way across the delivery chain.

Internal Realignment

One problem faced by procurement departments is a tactical, rather than strategic, focus from senior management. Rather than taking a holistic view of the total costs of owning a component, too often savings are extracted from the budget upfront, with the procurement department left to make ends meet on its own. Steve Coleman, director of transmission and distribution (T&D) sourcing for Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), stressed that procurement departments need to become strategic partners for their internal customers. That means making procurement a truly customer-focused, customer-facing organization.

Unfortunately, the traditional approach of having a dedicated supply chain for each business unit handicaps continuous improvement and implementation of best practices because these chains often become siloed and isolated from one another. These isolated chains are capable of acting strategically but are unable to fully capture savings and efficiencies available through more centralized operations.

One approach to making this work, though one that few utilities appear to have implemented, is to better align supply chains with their business units within a centralized supply chain organization. This is done by creating new roles within the supply chain that work directly with business units, focusing exclusively on understanding each unit’s plans and strategies, enabling them to engage with business unit initiatives very early in the process to represent supply chain concerns and demands.

Phil Seidler, supply chain director for Luminant, and Joe Levesque, vice president of product development for consulting firm PowerAdvocate, explained the benefits of this approach. Keeping these closely aligned supply chains within the centralized supply chain organization enables an ongoing focus on driving value, reducing risk, and improving supplier relations. The organization is able to create centers of excellence around common core functions and realize efficiencies and continuous improvement by exchanging information across the individual chains.

PG&E, for example, has added directors for each procurement unit to its organizational chart as well as a chief procurement officer, moving from a single vice president of general services overseeing two directors to a robust center-led, customer-facing organization. That’s allowed it to focus much more of its attention on strategic procurement, Coleman explained.

Engaging business unit leaders isn’t always straightforward, since convincing them that supply chain issues are worth their attention may be difficult. Seidler and Levesque listed some ways of meeting that challenge: understanding business unit objectives, knowing their business, and creating a pull relationship using information that demonstrates the value of alignment. When procurement has a clear understanding of the business unit’s needs and operations, it can better establish its credibility and demonstrate ways to improve performance.

Category Management

The concept of category management, in which procurement for classes of products is managed as an ongoing business in collaboration with suppliers, has been around in retail since the 1980s but is still making its way into utility procurement.

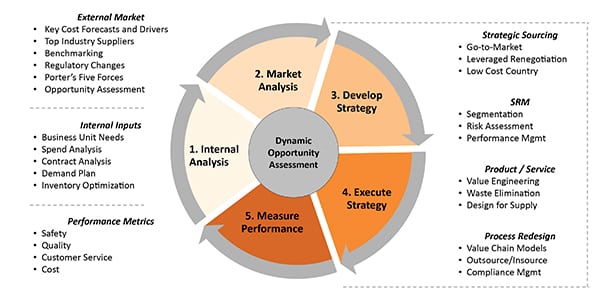

As Seidler and Levesque explained, category management is an evolution of strategic sourcing but is cyclical rather than linear (Figure 1). It is an ongoing process of continually tracking, managing, and improving the sourcing of material rather than an episodic, contract-focused process. It requires both alignment with business units and close collaboration with suppliers. This allows procurement to better engage business unit leaders to build lasting expertise in the supply chain, as well as respond proactively and swiftly to changes in the market.

Obviously, moving toward category management is not an overnight process. Luminant, Seidler explained, began the shift with its privatization in 2004 but only began getting a robust category management system into place in the 2010s. Getting the supply chains aligned with business units took several years, during which better strategies, skills, and metrics had to be developed.

Seidler and Levesque offered some other tips for making category management work most effectively:

- Start with categories that will quickly demonstrate high impact to business units to gain support early on.

- Set regular cross-functional business reviews with leadership to review process, spend, and other performance metrics.

- Structure roles such that responsibilities for strategic planning and day-to-day execution fall to different people.

- Embed category management inside technology tools to ensure that data, and the process, is sustained in the event of personnel turnover.

Supplier Integration

Of course, making all this work isn’t simply an internal process—suppliers have to be deeply involved as well. That’s why integrating suppliers into supply chain management is an increasing trend. While it’s not yet common, with the utilities furthest along in this process the supplier, procurement, and business unit function as a seamless supply chain, simultaneously sharing information up and down the chain. This level of cooperation and communication allows capturing efficiencies and cost savings that are not visible otherwise.

Stocking and inventory decisions are made collectively, depending on what options are most efficient and advantageous. Materials may be stocked with the supplier or the utility warehouse; management of many materials—particularly high-turn items needed regularly and/or rapidly—may be entirely in the hands of the supplier, who may assume direct responsibility for fulfillment goals with the business unit. In such a system, the supplier’s inventory essentially becomes the utility’s “virtual inventory.” If implemented effectively, the result can be lower labor costs, better resource availability, more efficient logistics, lower transactional costs, and better risk management.

Rodney Long and Ron Jangaon of Duke Energy explained how the utility giant has moved toward integrated supply with WESCO Distribution, which helps manage the program. Integrated supply programs generally comprise a number of components:

- Procurement and fulfillment are linked.

- Supplier has a fully transparent compensation model.

- Supplier provides on-site labor to augment purchasing and storeroom functions.

- Some on-site inventory is supplier owned.

- Service level metrics, including risk and reward components.

- Supplier also handles some third-party transactions.

One benefit of such deep integration, they explained, is better visibility of the total costs of material. The focus moves away from the contract price and takes in all the costs involved in sourcing, stocking, and using material.

Of course, not every supplier is capable or willing to take on these added responsibilities—it needs to be willing to partner with the utility for the long term. That means, said Gary D. Benz, supply chain vice president for FirstEnergy, keeping lines of communication open and making clear to suppliers that procurement is not a “one-off” process—the utility needs to make suppliers understand they’re building a relationship. But that flows both ways, he said. If a supplier is investing a lot of resources in that relationship, “They deserve to understand what our business plans are,” he said.

This approach takes on added complexity when dealing with overseas suppliers. Frequent communication is key, and organizations must be proactive in anticipating and dealing with potential language and cultural barriers. Having a dedicated procurement team that regularly travels abroad to meet with suppliers and review their operations can be highly beneficial, especially early in the relationship.

Michael Devoney, president and general manager of electrical and industrial distributor Turtle & Hughes Integrated Supply, related an example of a client who ran into difficulty managing supplier quality in China, where an increasing percentage of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) build their turbines and boilers. Unfortunately, he told POWER, “there are limited options to manage an approved vendor list (or to conduct supplier quality audits) in China.” This creates a market imbalance for the large OEMs, but if this need could be addressed, “more generators could buy ‘direct’ from the actual manufacturers,” he said.

Risk Management

Such a close partnership naturally brings with it some significant risks. How to manage supplier risk, whether in traditional concerns such as safety, quality, and performance, or more recent issues such as cybersecurity, becomes an increasing concern.

Speakers at the Platts conference all mentioned data security as a concern. When suppliers are deeply integrated into a supply chain, simply having a good internal cybersecurity policy in place isn’t enough. Supplier polices also need to be vetted and upgraded as necessary.

Scott Landrieu of PSEG discussed how natural disasters such as Superstorm Sandy and the Tohoku Earthquake (which led to the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant) have highlighted the need for having robust recovery plans in place in the event of severe disruptions of a supply chain. Utilities need to know what to do in the event that one or more major suppliers are knocked out of business or significant inventory stock is destroyed. Critical components should be sourced from multiple suppliers, and overseas supply chains should source from multiple countries to reduce the risk of potential disruptions. Here again, effective supplier integration can prove its worth, as entities across the chain can work together to mitigate risk.

Both speakers and attendees mentioned quality control as a key supply chain risk. Developing parallel supply chains for critical components, while potentially increasing costs, can greatly reduce the risk of nonperformance. This is especially true when sourcing from overseas.

Another source of risk is fuel price fluctuations. The fall in natural gas prices has increased pressure on other fuels. “Making peak operating periods has become more critical to overall profitability,” Chris Price of Turtle & Hughes told POWER. Likewise, pressure from renewable energy mandates complicates risk management. “It’s difficult to keep up on the technology and find the right sourcing partners,” he said. “Also, the focus on these initiatives changes with the regulatory landscape.”

Close alignment between all elements in a supply chain is important in reducing risk. This enables better visibility and identification of potential “choke points,” as well as communication of impending problems.

Inventory Optimization

Though “just-in-time” sourcing has become the standard in many industries, the power sector has lagged well behind this trend, in part because—especially in regulated markets—a utility’s focus is keeping the lights on and being able to respond rapidly to emergencies. While a bloated inventory full of stranded assets (spare components that the utility no longer has a need for) may not look good on the balance sheet, it rarely interferes with those priorities. Even in deregulated markets, poorly managed inventories don’t necessarily prevent a plant from competing effectively. But over the long term, inventory problems can represent significant drains on revenue.

Utilities and generators also have challenges not faced by other sectors. Critical replacement parts, some of which can be extremely expensive, must be kept on hand in case of emergencies even though they may never be needed. Utilities that operate in more than one state may be required to maintain duplicate inventories in order to meet requirements of separate state oversight. The problem can be compounded if the utility has merged with or been acquired by another company. Worse, the utility often may not have a clear picture of how much duplication exists or how much money is tied up in stranded assets.

Implementing advanced supply chain management processes can help address these problems. Just as category management, improved data, and better communication can streamline procurement, better information, segmentation, and tracking of inventory can assist a utility in identifying and clearing unneeded stores. Some utilities have made inventory management a separate director-level responsibility apart from other supply chain issues. Such a role is responsible for maintaining visibility and transparency into companywide inventory to be sure the utility has a clear view at all times into the location, quantity, and application of all stores.

Pat Pope, president and CEO of the Nebraska Public Power District (NPPD), reviewed his company’s experiences in challenging these problems. NPPD was experiencing annual inventory growth greater than 10%, about $13 million every year—despite previous efforts at bringing stocks under control. New inventory was coming in faster than procurement staff could clear out unneeded components. Yet, the situation was not viewed as a problem by many managers. The solution was not another ad-hoc reduction effort but engaging senior management in changing the way procurement operated so that supply chain personnel had the tools and authority to better match inventory to business unit needs—among these, inventory optimization software from Oniqua. The result was to completely reverse the unnecessary growth in NPPD’s inventory and actually reduce inventory by $8.2 million with no effect on reliability.

Steve Sotwick, Oniqua’s vice president of business development for North America, explained some ways in which inventory optimization can aid in supply chain management. Having a clear view of each business unit’s needs allows procurement staff to better identify critical inventory, forecast the needs for it, and spotlight inventory that is no longer needed. Creating separate inventory segments as part of category management allows category-specific inventory to be matched to that business unit’s strategies instead of applying across-the-board policies that are likely not appropriate for all stock.

Utilities or generators with multiple like-kind units will often centralize storage of critical spares that may be shared among their own units. This works well because the carry costs of the inventory can be spread among multiple plants. Sometimes this “part sharing” arrangement will occur between companies, with the arrangement often brokered through the manufacturer, though this is fairly rare. While this can reduce costs, a challenge arises if two plants require the same part. Careful planning and communication is also necessary to make clear who takes ownership of used parts. Because most major equipment can endure only so many refurbish cycles, plans must be in place for how that cost is shared.

Improved Metrics

Finally, all this fine-grained management is difficult to impossible to achieve effectively without accurate metrics to track how new strategies are working and without robust processes for using metric performance to drive improvements.

Most utilities have well-defined fulfillment metrics for their supply chains in place. Less common, however, is measuring flexibility and responsiveness, even though these metrics are critical for capturing efficiencies. It is also common for unplanned or rush orders to be excluded from metrics, even though these are the events most likely to result in supply chain disruption and extra costs.

Several speakers noted that advanced organizations are most likely to measure key metrics across the entire supply chain. More importantly, metrics need to be in place to measure business unit expectations, not just traditional procurement performance. Optimally, this takes the form of a service-level agreement (SLA) between procurement and the business unit. The SLA flows in both directions, spelling out not just expectations for order fulfillment but also business unit performance in accurate forecasts and communication of needs. The SLA also has to be a dynamic—rather than static—tool that is constantly being evaluated and updated to support continuous improvement of the supply chain.

Defining metrics is not always straightforward. Some, like order fulfillment, lend themselves easily to measurement; others, like employee skills or effective communication across the supply chain, are harder to measure accurately. Useful metrics need to flow from strategic goals while being tied into overall corporate objectives.

The Big Picture

It’s important to remember that not all supply chain management innovations necessarily support one another. Increased redundancy to reduce the risk of disruption, for example, can increase complexity of communication and performance metrics. An integrated supplier network has more parts to monitor, increasing the risk of losing focus on the whole. Successful companies will maintain a holistic approach in managing their supply chains, making visibility, flexibility, and collaboration key priorities. ■

— Thomas W. Overton, JD is a POWER associate editor.