South Carolina’s largest power provider Santee Cooper has issued a request for proposals (RFP) aimed at finding a buyer—or visionary—to take on what remains of the Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Station expansion. The two partly constructed AP1000 projects, abandoned in 2017 after a cascade of delays and cost overruns, could now offer a second chance to deliver much-needed carbon-free power at a pivotal time for the energy industry, the utility said.

Santee Cooper on January 22 said it engaged investment bank Centerview Partners to conduct the RFP. The effort will seek “parties interested in acquiring the project and related assets, and potentially completing one or both units or pursuing alternative uses of the assets,” it said. Responses are due to Centerview on May 5, 2025.

The move marks a pragmatic shift for Santee Cooper, South Carolina’s state-owned electric and water utility, which owns the abandoned reactors. While Santee Cooper has not indicated plans to own or operate the units if completed, the utility recognizes the site’s strategic value. “We are seeing renewed interest in nuclear energy, fueled by advanced manufacturing investments, [artificial intelligence (AI)]-driven data center demand, and the tech industry’s zero-carbon targets,” said Jimmy Staton, Santee Cooper’s president and CEO.

“Considering the long timelines required to bring new nuclear units online, Santee Cooper has a unique opportunity to explore options for Summer Units 2 and 3 and their related assets that could allow someone to generate reliable, carbon emissions-free electricity on a meaningfully shortened timeline,” he said.

Reviving an Abandoned Project

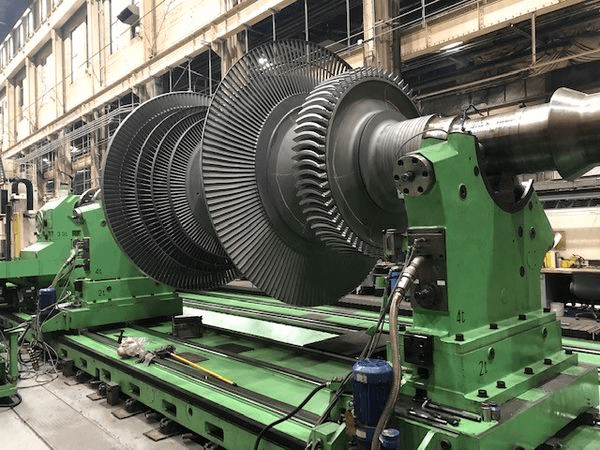

The 973-MW V.C. Summer facility, located in Jenkinsville, South Carolina, is a single-unit Westinghouse three-loop pressurized water reactor power plant completed in 1984. In 2008, SCANA Corp. and Santee Cooper launched a partnership to build two 1.1-GW AP1000 nuclear units as part of a $9 billion expansion project. The project garnered combined construction and operating (COLs) from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in 2012.

From its inception, the V.C. Summer expansion, along with a similar expansion spearheaded by Southern Nuclear for two AP1000 units at Plant Vogtle near Augusta, Georgia, were championed as the centerpiece of the U.S. nuclear renaissance. However, both projects suffered escalating costs and crippling delays, compounded by regulatory design changes, supply chain inefficiencies, and mismanagement. In March 2017, Westinghouse, overwhelmed by financial losses from its fixed-price EPC contracts for the AP1000 reactors at V.C. Summer and Plant Vogtle—and further exacerbated by its ill-fated acquisition of CB&I Stone & Webster and partner Toshiba’s inability to sustain the burden—filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

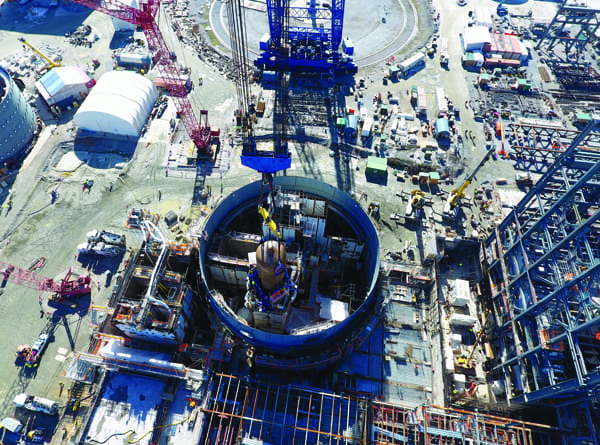

SCANA and its utility partner Santee Cooper announced their decision to abandon the two-unit V.C. Summer nuclear expansion on July 31, 2017. The project was about 64% complete. When it abandoned the project, SCANA cited cost concerns, noting that its share of costs to finish the project as 55% owner would have soared to $9.9 billion, while Santee Cooper, which owned the remaining 45%, said it would have needed to spend about $8 billion to complete construction, plus about $3.4 billion for interest. The partners said the decision would save customers nearly $7 billion.

The controversial halt to the V.C. Summer project marked the beginning of SCANA’s rapid decline, driven by backlash from ratepayers, lawsuits, and federal investigations over its handling of the failed expansion severely damaged the company’s reputation and finances. The turmoil ultimately led to SCANA’s acquisition by Dominion Energy in 2018 for $14.6 billion in a deal that included significant concessions to ratepayers and shareholders aimed at stabilizing the power company’s future. Dominion continues to recover capital costs and a return on capital cost rate base related to the project, which are scheduled over a 20-year period through a capital cost rider.

In January 2019, Dominion Energy completed its acquisition of SCANA and transferred SCANA’s 55% ownership stake in the partially completed AP1000 units, along with associated project assets, to Santee Cooper. The transaction made Santee Cooper, which previously held a 45% ownership stake, the sole owner of the V.C. Summer Nuclear Project. Later, in August 2020, Santee Cooper finalized a settlement agreement with Westinghouse that granted the utility full control and ownership of the project site, including all non-nuclear and nuclear-related equipment, materials, and intellectual property associated with the AP1000 reactors.

Separately, the expansion at Plant Vogtle—including completion of Vogtle 3 and 4—in Georgia was ultimately achieved last year. Originally projected to cost $14 billion, the total cost has surged to over $30 billion, with the co-owners—Georgia Power, Oglethorpe Power Corp., Municipal Electric Authority of Georgia, and the city of Dalton—incurring approximately $21 billion in capital construction costs after factoring in nearly $4 billion recovered from Toshiba’s parent guarantee following Westinghouse’s bankruptcy. Despite significant cost overruns and criticism, the Vogtle expansion has been hailed as a cornerstone for the future of nuclear energy in the U.S., and it remains symbolic of a crucial starter project that broke a three-decade-long commercial stalemate for nuclear power.

A Troubling History of Abandoned Nuclear ProjectsOver the decades, more than 100 nuclear projects have been abandoned, many of them well into construction. To learn more, see POWER’s comprehensive infographic, The Big Picture: Abandoned Nuclear Power Projects, published in February 2018. |

Riding on New Optimism for Nuclear

Today, interest in repowering nuclear projects, long dismissed as impractical, is gaining traction as the U.S. grapples with rising electricity demand and decarbonization goals. In September 2024, Microsoft and Constellation Energy committed $1.6 billion to restart the Unit 1 reactor of the shuttered Three Mile Island plant in Pennsylvania by 2028, now known as the Crane Clean Energy Center. Last year also cemented efforts to restart the 800-MW Palisades nuclear plant in Michigan. New prospects are emerging fluidly, driven in large part by optimism to support the burgeoning advanced nuclear sector, which could usher in a new generation of smaller, safer, and more versatile reactors.

Last year, the Department of Energy suggested nuclear capacity could potentially triple from 100 GW in 2024 to 300 GW by 2050 if key barriers are overcome. The agency cited a convergence of factors that have reshaped nuclear’s value proposition. After decades of relative stasis, electricity demand is surging due to the rapid growth of artificial intelligence applications and data centers, which require carbon-free, 24/7 generation within a compact footprint. The shift, in turn, has created a new class of customers willing to invest in nuclear power as a reliable, emissions-free solution. Incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), along with bipartisan support for nuclear, have further enhanced nuclear’s economic attractiveness, it said.

On Tuesday, Santee Cooper emphasized similar factors that make the V.C. Summer expansion’s completion particularly compelling, including the urgent need for “new generating capacity, driven by rapid growth in data centers, the continued onshoring of advanced manufacturing and the retirement of fossil units.” The utility also pointed to a growing national interest in repowering previously abandoned or delayed nuclear projects as a way to shorten construction timelines for advanced energy infrastructure. “Unit 2 was significantly progressed when the project was canceled,” it noted.

The utility also said that V.C. Summer is uniquely positioned “as the only site in the U.S. that could deliver 2,200 MWs of nuclear capacity on an accelerated timeline.” Its location “within the nuclear security ‘envelope’ of the larger V.C. Summer station site” was “always intended to hold multiple units,” it added. The site also has access to “ample land, water, and transmission infrastructure upgrades built to accommodate output from the units.”

The project’s revival, pivotally, also has support from key factions within the state of South Carolina. In December 2024, the state’s Governors Nuclear Advisory Council published a “resolution of support” for the project’s completion. A September 2024 inspection of the abandoned units “found them in good condition, with significant amounts of well-preserved parts, fully operational warehouses, and major infrastructure components already in place,” the resolution states. In addition, the project remains approximately 45% complete [Unit 2 is at about 48% and Unit 3, significantly less], and the Westinghouse engineering drawings for the AP1000 units are now complete, which will speed construction and reduce costs,” it notes.

The resolution also underscores a growing urgency to complete the project, noting that “coal-fired power plants representing 14% of South Carolina’s electrical generation are scheduled to shut down within the next few years,” while emphasizing that nuclear provides “a reliable baseload energy source that does not produce carbon dioxide.” It calls for a “thorough inspection and analysis of the cost and construction schedule to complete the project.” If the findings are “positive,” it urges the project owners and South Carolina legislature to collaborate on achieving the goal of plant completion.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).