Recent months brought several developments in Europe’s much-touted "nuclear renaissance."

Spain Extends Life of Nation’s Oldest Reactor

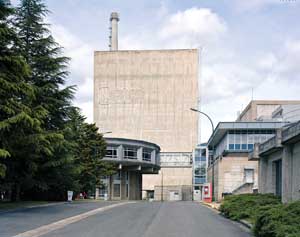

Spain’s government on July 2 granted a four-year extension to the operating permit of the 466-MW Santa María de Garoña nuclear power plant (Figure 3). The decision follows a nonbinding recommendation by Spain’s nuclear regulator in June to issue a 10-year operating permit extension for the 38-year-old plant that was scheduled to be decommissioned in 2011 — on the condition that it is modernized. That would cost operating companies Iberdrola and Endesa an estimated €50 million, but it is an investment they are willing to make.

3. A half life. Spain’s government in July granted a four-year extension to the 466-MW Santa María de Garoña nuclear power plant, a 38-year-old plant that is by far the country’s oldest nuclear plant. Spain’s prime minister said the country needs the energy, even though the plant produces about 1% of the nation’s electricity. Courtesy: Foro Nuclear

The plant is by far the oldest remaining nuclear plant in Spain. Lobbyists in the country have been pushing to extend the plant’s operating life, saying that Spain needs nuclear power to support the nation’s rapidly growing renewable energy portfolio. Environmentalists, meanwhile, have demanded the plant’s total shutdown because they claim the reactor has suffered from severe cracking, and that corrosion has affected various components in the reactor vessel.

Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero defended the government’s decision, saying that Spain needs the energy and the Garoña area needs the economic activity — even though the plant produces only about 1% of the country’s electricity, has aging technology, and produces 50% more high-level waste than Spain’s other five nuclear plants.

Nuclear power produces 20% of Spain’s electricity, but permits for running most of the other plants will also expire by 2011 — or within the mandate of Zapatero’s government. A decision to prolong the life of the Garoña plant on the Ebro River is a major reversal for Zapatero, who, during general elections in 2004 and 2008, pledged to gradually phase out nuclear power.

German Nuclear Policy Depends on Upcoming Election

Nuclear power in Germany may see new life following the Sept. 27 general election. The country’s government in 2000, under Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, agreed to phase out all of the country’s 17 reactors by 2021. But the looming power gap of around 21 GW — nearly 25% of the country’s overall power production — could strong-arm Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats and the Liberal party to postpone the closures. The Social Democrats continue to push for the phase-out, however, in favor of renewable energy such as wind and solar power.

The election in September could, therefore, decide whether or not the phase-out continues. Reports from the nation’s political media say the race is too close to call but that opinion polls show Merkel’s Christian Democrats and Liberals are gaining public favor.

Bulgaria Desperate for Investors to Save Belene

Bulgaria’s center-right government said in late July that if it does not find private investors for its majority stake in the planned Belene nuclear power plant, it will be forced to abandon the project. Owing to tight global liquidity and the recession, the government said it cannot afford to take on loans to fund its 51% stake in the 2,000-MW plant.

The previous Socialist-led administration wanted to build Belene — the country’s second nuclear plant — on the Danube River to recover Bulgaria’s position as a major power exporter in the Balkans. The country had contracted Russia’s Atomstroyexport, France’s Areva, and Germany’s Siemens to build Belene. Then it picked, with much fanfare, German utility RWE for the remaining 49% in the €4 billion Belene plant.

Since then, analysts estimate that project costs have surged to more than €6 billion. The previous administration had even negotiated a €3.8 billion state loan with the Russian government, but the new government says it is not willing to provide any state guarantees for loans.

Financial Crisis Impacts Russia’s Grand Nuclear Plans

Russian state nuclear corporation Rosatom said in mid-July that the global economic slowdown has affected its extensive nuclear power plant construction program. According to the so-called "Master layout plan for energy-producing capacities projected up to 2020," the current approved schedule in April 2007 (and then amended and re-endorsed in March 2008) calls for 36 new nuclear reactors to be built in the next decade. The program envisaged starting up one unit per year from 2009, two from 2012, three from 2015, and four from 2016. Nuclear capacity was expected to almost triple by 2020.

"Today, under crisis conditions, the time frame when we will need three to four [nuclear plant equipment] sets [per year] will be pushed back, but it will not be cancelled, just pushed back, taking into account the changing demand in energy. As we come out of the crisis, we will be needing all of this again," Rosatom head Sergei Kiriyenko reportedly told journalists in March this year.

This July, he confirmed that in the face of the financial crisis and declining energy demand, the nation had decided to put off the peak of the program for several years. "We had planned to construct two reactors per year, but we have now revised the program and now, in the coming years, we will build one reactor per year," he said.