India and Russia on Apr. 1 said they had devised a significant deal that will allow the first import of nuclear reactors in India, despite India’s 2010-passed nuclear liability law that allows nuclear power plant operators to hold a supplier responsible for an accident if the cause is blamed on equipment defects.

The law has stalled the implementation of deals for new reactors that India signed with the U.S., Russia, and France in 2008, when the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) allowed India to import nuclear fuel technology without being a member of the multinational body concerned with reducing nuclear proliferation. India said the breakthrough deal with Russia reached this April after four years of negotiations takes into account the liability law when pricing four more Russian reactors meant for India’s Kundankulam plant in Tamil Nadu (each of which is valued at $2.5 billion) as well as four or six other VVER-1200 units planned for Haripur, West Bengal. The deal essentially calls for India’s public sector General Insurance Co. to evaluate each component of the Russian reactors and prescribe a 20-year insurance premium it will charge to cover Russia’s liability for an accident.

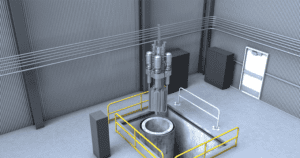

Russia’s state-owned nuclear firm Rosatom reportedly has indemnity from any liability arising from an accident at the VVER-1000s at Kundankulam Unit 1 (Figure 2), which attained criticality in July 2013 and is expected to come online later this year, and Unit 2, expected to be operational in October 2014. Observers note that contracts for those plants were signed in 1998, before India’s domestic liability legislation had even been contemplated.

Before Indian legislation on civil nuclear liability—The Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Bill—finally passed both houses of parliament in August 2010, exempting suppliers from all liability had been India’s typical practice, starting in 1962, when India signed its first nuclear cooperation agreement with the U.S. to allow General Electric to supply two 200-MW reactors to India’s Tarapur site. The practice of liability exemption was modeled on America’s own 1957-passed nuclear liability law, the Price Anderson Act, and went on to extend indemnity protection to Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. for two reactors in Rajasthan in 1965, and later to Russia.

Ironically, India only passed its 2010 nuclear liability law to boost its credibility and as a last step to activate the 2008 Indo-U.S. civilian nuclear agreement, because U.S. nuclear reactor manufacturing companies require a liability bill to get insurance at home. In return for Washington’s help in persuading the NSG to create an exemption that allowed its members to engage in nuclear trade with India (even though the country is not a signatory to the nonproliferation treaty), per the 2008 agreement, India committed to buy U.S. reactors worth 10 GW—roughly $50 billion or more in reactor sales.

And in fact, the final Indian liability law actually quashes an “absolute liability” mandate established by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the 1984 Bhopal disaster, in which 15,000 people died after methyl isocyanate leaked from a plant run by U.S. company Union Carbide and whose cause was pinned to corporate negligence. It caps the liability of the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd., India’s state-owned nuclear firm that owns all of the country’s commercially operating reactors, at about $250 million. But though the government stealthily attempted to prevent it, the final law also contains a clause—a “right to recourse”—that allows the public sector company to reclaim some of those funds from a supplier.

Significantly, the April-drafted India-Russia liability deal could serve as a template for a similar government-to-government pact with France, whose state-owned nuclear firm AREVA has proposed to build two EPR reactors in Maharashtra, India said. But for the U.S., the “right to recourse” clause remains a major deterrent.

Though U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz met with Indian officials March 11–12 for an ongoing India-U.S. energy dialogue, the two countries are reportedly no closer to resolving their stalemate over the nuclear liability law. For U.S. suppliers like Westinghouse—the American unit of Japan’s Toshiba Corp. that has proposed to build an AP1000 reactor in Gujarat—and for GE-Hitachi, which has been in talks with India for years for six proposed ESBWR units in Andhra Pradesh, efforts to develop nuclear projects in India have been frustrating, despite the 2008 Indo-U.S. civil nuclear agreement.

The companies contend that specific sections of the nuclear liability act violate the International Atomic Energy Agency’s International Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC). Though the 1997-adopted CSC has 17 country signatories, only four countries have ratified it, and until five signatory countries with a minimum of 400 GWth of installed nuclear capacity (a third of all the world’s currently operable reactors) ratify it, the convention cannot pass into force. Last December, Canada signed the CSC, and Japan announced plans to become the fifth country to ratify it, but that hasn’t happened yet. And while India is a signatory of the CSC, it will continue to rely on its own law covering nuclear liability, which it blankly refuses to “dilute,” as officials told the U.S. energy dialogue delegation in March.