The Department of Energy (DOE) has issued a request for information (RFI) on a planned temporary federal program to ensure enough high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU) will be available to jumpstart deployment of a new fleet of advanced nuclear reactors.

Comments received over the next month in response to the DOE’s Dec. 14–issued RFI will inform development of the planned “HALEU Availability Program,” which the agency is authorized to establish and carry out under the Energy Act of 2020. As envisioned, the HALEU Availability Program will seek to secure a supply of HALEU to support research, development, and demonstration of advanced reactors for commercial applications until a viable domestic commercial supply can be established, the DOE said on Tuesday.

More than 40 metric tons of HALEU may be needed by 2030 “with additional amounts required each year to deploy a new fleet of advanced reactors in a timeframe” that supports the Biden administration’s net-zero emissions targets by 2050, the DOE suggested. However, because the government’s existing defense-related HALEU supply is already tight and no commercial “domestic assured” source of HALEU yet exists, a glaring fuel supply gap threatens to overwhelm interest and investment in the burgeoning advanced reactor industry, it said.

Under the planned HALEU Availability Program, the DOE intends to set up an industry-led “HALEU consortium” that will partner with the DOE to support HALEU availability for “civilian domestic demonstration and commercial use.” But the DOE also envisions that the temporary program will “sunset” in 2034, ultimately removing the government from “any role as a supplier of HALEU for industry,” the agency said.

A Mounting Urgency to Make HALEU Available

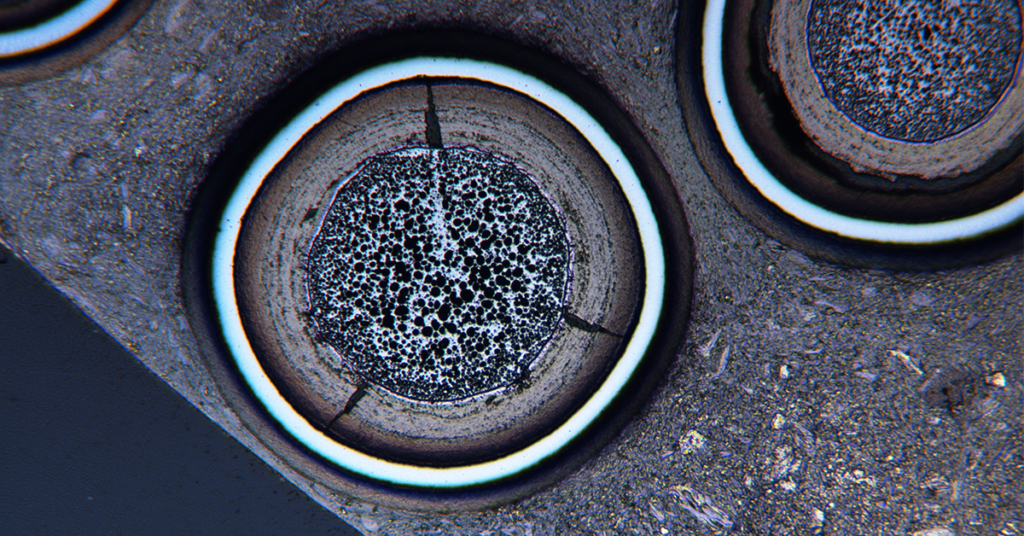

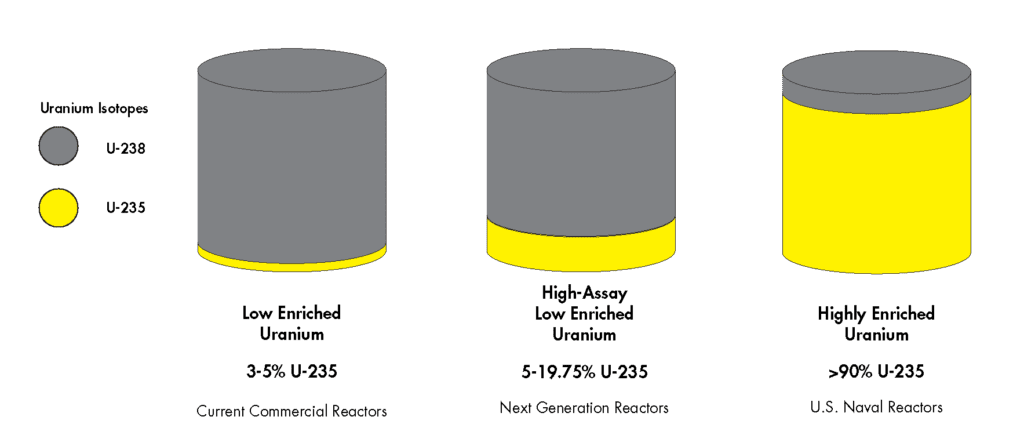

As POWER has reported, HALEU is a nuclear fuel material enriched to a higher degree (between 5% and 20%) in the fissile isotope U-235. It is not commercially available in the U.S., but it may be required in the future to fuel advanced reactors—including some microreactors (smaller than 10 MW), high-temperature gas reactors in the 100-MW to 200-MW range, and salt reactors. HALEU could also be used in existing light water reactors, such as with accident tolerant fuels, as well as in military microreactor applications. Experts note that because HALEU is enriched higher than the 4% to 5% level typically used in existing reactors, units utilizing it may provide more power per volume than conventional reactors, and its efficiency allows for smaller plant sizes. It also promises longer core life and a higher burn-up rate of nuclear waste, it notes.

Centrus HALEU Demonstration Challenged by Pandemic Hurdles

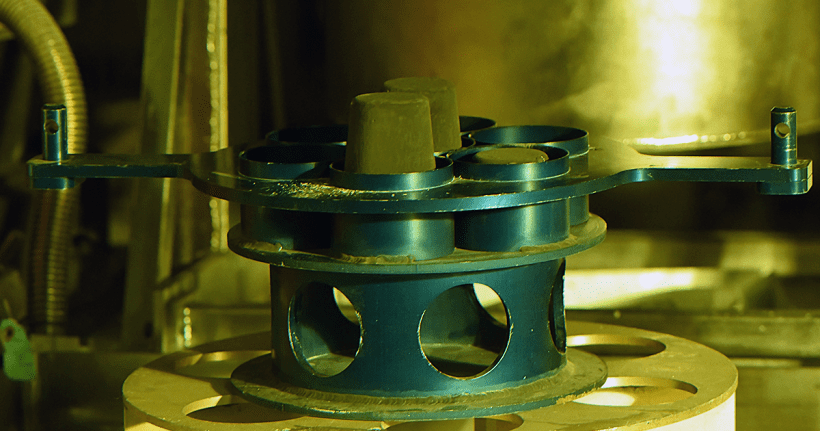

Yet, to date, only one firm—Centrus Energy—is slated to begin production of HALEU with domestic technology. Centrus, a spinoff of the government-held USEC, in October 2019 formally signed a three-year $115 million cost-share contract with the DOE to demonstrate production of HALEU for advanced reactors. While the DOE’s existing contract with Centrus ends on June 1, 2022, Centrus in November noted it has “experienced increased delays from vendors and increased costs due to the continuing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.” Supply chain difficulties have also affected the DOE in its supply of equipment under the contract, the company noted.

| See “Centrus on Track to Produce HALEU Nuclear Fuel Material by Early 2022” for an in-depth exploration of how Centrus plans to produce HALEU. |

Centrus also suggested costs required to complete the existing HALEU contract have jumped about $10 million over the 2019 estimate. “Further, while we still anticipate completing the cascade in 2022, due to a COVID-related supply chain delay in the DOE-supplied HALEU storage cylinders, production will not begin until mid-2022,” it said. Centrus noted that owing to these factors, the DOE on Oct. 28 increased the government’s cost-share ceiling to $117.9 million.

Looking ahead, the DOE’s Fiscal Year 2022 budget request calls for $33 million to establish the new HALEU Availability Program. It includes “a portion” that could be used to continue support for the 16 Piketon machines. As notably, the DOE has suggested it may change the scope of the existing contract, “including moving the operational portion of the demonstration to a new, competitively-awarded contract, with operations to begin in mid-2022,” Centrus said.

However, the company also cautioned that though “it is well-positioned to compete for a follow-on contract to operate the machines in Piketon,” no assurances exist that the DOE will award that contract to Centrus. “Congress has not yet adopted a Fiscal Year 2022 appropriations bill for the Department, and there is no assurance that the proposed program, which would go beyond the scope and expiration of our existing contract, will be approved and funded,” it said.

The Existing HALEU Supply Profile

Outside of Centrus’s potential HALEU supply, the U.S. faces a tight domestic capacity to provide HALEU from either DOE or commercial sources. “This lack of capacity is a significant obstacle to the development and deployment of advanced reactors for commercial applications,” the DOE noted.

Other domestic avenues of HALEU supply include efforts from the DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which provides highly enriched uranium (HEU), HALEU, and low-enriched uranium for its defense and nonproliferation missions. But most of the NNSA’s HEU is reserved for the Naval Reactors program and for use in the nuclear weapons stockpile, and is therefore unavailable for down-blending to use in advanced reactors used for commercial applications. Other HEU in the inventory is allocated to supply research reactors and medical isotope production facilities around the world, and for critical defense and space requirements.

“After accounting for these requirements on the inventory, the remaining amount of HEU to be down-blended to HALEU for advanced commercial reactors is very limited,” the DOE said. “If these supplies were redirected to fuel advanced commercial reactors, they would not be sufficient to meet the projected near-term demands for advanced reactor demonstration and deployment. Furthermore, diverting these resources to support advanced reactor demonstration and deployment would compromise vital nuclear security and nonproliferation missions.”

RFI Seeks Input on Broad Challenges, Immediate HALEU Needs

The DOE’s RFI, which is set to close on Jan. 13, 2022, will seek comment or information on several questions. Some are broad, suggesting some flexibility on the direction the DOE will take. It asks, for example, which types of organizations or entities it should include in the HALEU consortium, the body that the Energy Act of 2020 designates to ultimately inform the DOE on commercial HALEU supply needs. It also generally seeks input on “significant barriers to the establishment of a reliable market-driven, commercial supply of HALEU for advanced reactor research, demonstration, and commercial deployment.”

Other questions focus narrowly on the near-term, asking for example, how much HALEU will be necessary for domestic commercial use for each of the next five years (2022–2026). The RFI also seeks industry’s perspective on how large a HAELU “stockpile” would need to be to build their confidence in a HALEU supply. The DOE, notably, also asks for specific actions that would provide “confidence” in the short-term supply of HALEU.

The RFI also recognizes that HALEU use by the wide range of advanced reactors under development would vary “in various chemical and physical fuel forms, including oxides, metals, and potentially salts. Additionally, centrifuge enrichment requires uranium in hexafluoride form.” It asks about related fuel cycle infrastructure that will be necessary to enable production of commercial HALEU and assure the availability of its different forms.

Another notable set of questions relates to HALEU valuation. “On what basis should HALEU be priced or valued?” the RFI asks. “Please consider the options for the pricing of HALEU based on enrichment, weight, and/or separative work units and provide the pros and cons for each option or combination of options. Please discuss how pricing options would provide DOE with reasonable compensation and commercial entities with sufficient incentive to deploy domestic capacity to supply HALEU. What is your long-term estimated ‘price point’ for the range of assays/enrichment (2030 and beyond),” it asks.

Several other questions relate to transportation packaging, regulatory issues—including safety, security, and licensing—financial barriers, and human resource–related considerations.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).