A federal appeals court has struck down a key Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) program for reducing fine particulate and smog-causing emissions in the eastern half of the nation, saying the rules were riddled with “several fatal flaws,” including the agency’s failure to properly focus pollution cuts to prevent movement of air pollution from one state from worsening air quality in a downwind state.

Gone But Not Forgotten

In its July 11 ruling (PDF) against the EPA on disparate issues raised by electric utilities, North Carolina, and one municipality, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit noted that the EPA’s Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR) was supposed to enforce Clean Air Act provisions specifically requiring the agency to ensure that pollution from one state did not significantly contribute to a downwind state’s inability to meet federal clean air standards or to stay in compliance with those standards.

However, in citing numerous legal problems with various aspects of CAIR, the judges repeatedly rapped the EPA for developing and imposing CAIR emission reductions requirements without showing that they fairly addressed the specific pollution contributions made by specific upwind states to specific downwind states.

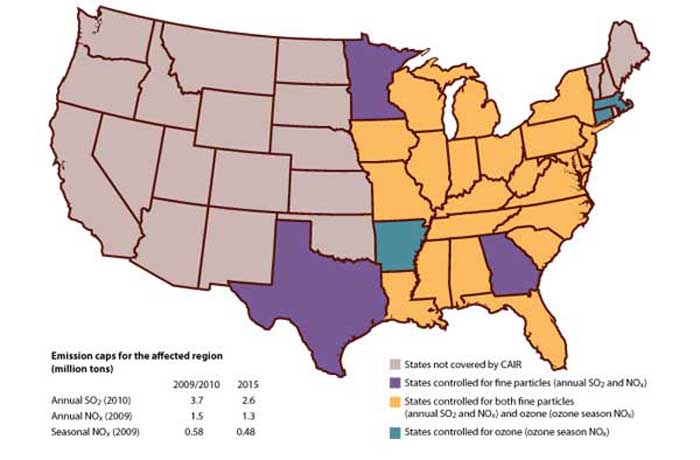

To the contrary, the court said that in apportioning pollution cuts over 28 states and the District of Columbia to meet a region-wide goal for reducing emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) from power plants, the agency failed in many cases to find out how much an upwind state was affecting a downwind state, and failed to tailor its state-by-state emissions caps to address those specific contributions by upwind states to pollution in downwind states (Figure 1).

1. Affected regions and emission caps prior to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit’s July 11, 2008, decision that struck down the CAIR regulations. Source: EPA

As a result of that lack of linkage, the court repeatedly ruled that CAIR requirements and deadlines set by the EPA were arbitrary, capricious, and outside the scope of the agency’s authority under the Clean Air Act provision on interstate air pollution.

“EPA’s approach—region-wide caps with no state-specific quantitative contribution determinations or emissions requirements—is fundamentally flawed,” the court said. “EPA must redo its analysis from the ground up.”

No Options Remain

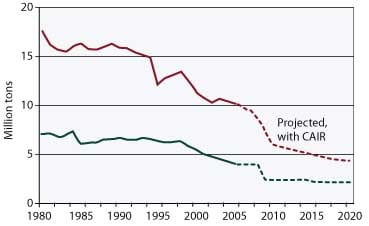

The court acknowledged concern that throwing out the entire CAIR rule—rather than letting the agency fix the problems cited in its opinion—would delay the substantial emissions reductions that would be achieved by the program (Figure 2).

2. Historic national NOx and SO2 power plant emissions and those projected with CAIR. Source: EPA

The rule was to have been implemented in two phases, beginning in January 2009 for NOx emissions cuts and 2010 for SO2 reductions. The EPA estimated that in 2010 the program would reduce SO2 emissions by 4.3 million tons across the eastern United States and by 5.4 million tons in 2015. Smog-forming NOx emissions would have been cut 2 million tons annually under full program implementation, about 60% from current levels. A second round of NOx and SO2 cuts was to start in 2015.

However, the court said some of the NOx emissions reductions could still be achieved under an earlier program instituted by the EPA to reduce NOx emissions in eastern states—the so-called NOx SIP Call program. While CAIR superseded that program, the court noted the NOx SIP Call initiative would be revived with the death of CAIR because the EPA terminated the NOx SIP Call only as part of its CAIR rulemaking.

Few in Agreement

Nonetheless, the court’s decision appeared to perturb both environmentalists and utility industry officials.

Officials at Environmental Defense Fund, noting that the NOx SIP Call program only was operative during the summertime, said action was needed to resurrect tougher controls. “The government should take immediate corrective action to protect the millions of Americans hard hit by power plant pollution,” said Vickie Patton, deputy general counsel at Environmental Defense Fund.

“Many states and communities were counting on the EPA rules to help them comply with health-based clean air standards,” added Conrad Schneider, director of the Clean Air Task Force, who called on the EPA to quickly issue a legally valid rule. Failing that, he urged Congress to “step in and protect the breathing public,” noting that Sen. Tom Carper (D-Del.) has introduced bipartisan legislation to sharply reduce power plant emissions of SO2, NOx, and mercury.

From the industry perspective, the Edison Electric Institute, which represents investor-owned electric utilities, said the court ruling created unwanted uncertainty at a time when many utilities already are moving ahead with costly pollution control measures to meet CAIR requirements.

“We are rather surprised by the sweeping nature of this decision, which essentially sends the whole rule back to the drawing board,” EEI said in a statement. “Overall, our industry was supportive of the emission reduction goals under CAIR. Now we are faced with considerable uncertainty about the path forward for improving air quality.

“The electric power sector already has slashed emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides by 50% under existing law, but CAIR would have deepened those reductions to 70% to 80%. Now it likely will take several years to devise new rules.”

Industry Experts Surprised

Industry officials showed particular interest in parts of the court ruling in which the judges rejected the voluntary emissions trading plan created by the EPA to reduce CAIR compliance costs for utilities. They suggested the ruling might raise legal questions about instituting a cap-and-trade program under the Clean Air Act to reduce greenhouse emissions.

However, the court’s ruling on CAIR’s trading system appeared to be narrowly based on the specifics of the interstate air pollution provisions of the Clean Air Act.

As with the federal acid rain trading program, CAIR set an overall goal for emissions reductions and then apportioned the cuts among individual states and power plants. Each state and plant was allocated emissions allowances to enforce their required reductions; those reducing emissions below their ceilings could sell allowances to those that exceeded their limits. Any state not agreeing to participate in the trading program had to develop its own emissions reduction requirements to meet its apportioned pollution cut.

North Carolina challenged the trading program, saying the emissions cuts apportioned to some states near its borders might not curb the pollution sent by those states into North Carolina. For example, North Carolina officials said while Alabama plants were contributing to excessive air pollution in their state, those plants could theoretically not make any reductions by simply buying allowances from other plants.

The EPA acknowledged that CAIR might not address specific interstate problems but said its program was specifically designed to prevent harmful interstate air pollution transport by bringing down emissions across the entire region.

However, the court ruled that the region-wide nature of the EPA’s emissions reduction goal and trading program was problematic in light of the statutory purpose of the CAIR program to ensure that one state is not unfairly polluting another.

“CAIR must do something more than achieve something measurable; it must actually require elimination of emissions from sources that contribute significantly [to pollution] in downwind nonattainment areas,” the court said.

On other issues, the court:

• Agreed with utilities that the EPA could not limit use of SO2 allowances in the acid rain compliance program to prevent CAIR emissions reduction requirements from effectively creating a surplus of SO2 allowances for utilities in some states.

• Ruled that the EPA was wrong to give more CAIR NOx allowances to coal-fired power plants than oil- and natural gas–fired power plants to help balance out the higher compliance costs facing coal-heavy states. “EPA’s redistributional instinct may be laudatory, but [the Clean Air Act’s interstate provision] gives EPA no authority to force an upwind state to share the burden of reducing other upwind states’ emissions,” the court said.

• Rejected the EPA’s choice of a final 2015 deadline for upwind states to curb emissions hurting downwind states, saying the agency provided no good reason other than cost for waiting until then to address interstate pollution transport problems.

—George Lobsenz (globsenz@accessintel.com) is executive editor of COAL POWER’s sister publication, The Energy Daily (www.theenergydaily.com).