The fate of coal-fired generation remains fluid as owners weigh environmental rules, the effect of low natural gas prices, and the shifting cost of investing in emissions control technology. An analysis of generating unit data suggests that smaller, older, less-efficient, and less-frequently dispatched assets are most vulnerable to retirements. Recently accelerated retirement dates for some units indicate that economic factors are a more important determining factor than pending environmental mandates

Two of the nation’s largest consumers of coal for electric power generation said in July that their cost to comply with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) emissions rules will be less than they initially thought.

Four other utilities announced plans either to close coal-fired generating units or invest in emissions control equipment to meet the pending EPA rules. And an independent power producer whose generating capacity is largely fueled by natural gas said that economics—not environmental rules—will continue to favor natural gas over coal and spur retirements among coal-fired units.

“Coal plant retirement should increase significantly from today’s announced levels as companies re-evaluate the economics of their compliance decisions, especially since the more costly environmental rules like once-through cooling and coal ash disposal are still in their infancy in Washington,” said Jack Fusco, Calpine CEO during an earnings conference call.

The news in recent months suggests that the cost of complying with myriad EPA rules (see “THE BIG PICTURE: Regulation Road” on p. 10 for an overview) remains unsettled. Estimates vary as to how many generating units ultimately may be retired and whether or not their loss will affect reliability. Complicating things is the continued low cost of natural gas that is putting competitive pressure on coal-fired units.

Indeed, Jeffrey Immelt, CEO of General Electric, was quoted by the Financial Times newspaper in late July as saying that gas-fired generation is becoming “permanently cheap.” The pressure exerted by low-cost natural gas affects the prospects not only of coal-fired generation, but also of nuclear generation. “It’s just hard to justify nuclear, really hard,” Immelt was quoted as saying. “Gas is so cheap and at some point, really, economics rule.”

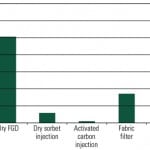

Fusco echoed Immelt’s comments during his July quarterly earnings conference call with analysts. He said that although many coal-unit retirements have been attributed to pending environmental rules like the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS), “a closer look at the facts suggest that retirement decisions may have nothing to do with environmental regulations at all and everything to do with economics brought about by sustainable lower natural gas prices.” He continued, “In the current natural gas price environments, coal plants are financially challenged even before considering the installation of expensive environmental retrofits” like scrubbers, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems, baghouses, and flue gas desulfurization (FGD) equipment.

What’s more, Susan Tierney, a former Department of Energy official and managing principal with Boston-based Analysis Group Inc., told POWER in an interview, “The bright signal is that if units that are inefficient or uncontrolled were to be retired due to EPA rules, they would do so in a couple of years.” Instead, the fact that many generating units are retiring in advance of EPA compliance deadlines suggests that current economics rather than environmental rules may be the dominant deciding factor. (Tierney wrote “Why Coal Plants Retire: Power Market Fundamentals as of 2012” for the July/August issue of COAL POWER, at http://www.coalpowermag.com.)

Revising Compliance Costs

Then, too, compliance costs are being recalculated by some of the nation’s most coal-dependent power generators. In late July, Nick Akins, CEO of American Electric Power (AEP), told analysts the utility was revising down the cost of complying with EPA regulations. “When we first started this process, we were looking at $8 billion, and it’s come down to just over $6 billion,” Akins said, adding that the utility expects its compliance expense “to continue to be refined.”

|

| 1. Expensive scrubber. Wisconsin Power & Light asked state regulators in July for permission to add sulfur dioxide scrubbers to its Edgewater Unit 5 at a cost of up to $430 million. Courtesy: Alliant Energy |

|

| 2. End of the line. Black Hills Energy–Colorado Electric plans to suspend operations at its 42-MW W.N. Clark plant at year-end and retire the facility by the end of 2013. Courtesy: Black Hills Corp. |

Akins said that installing scrubbers on AEP’s coal units posed a “relatively high hurdle” and that “in some—in many cases—it’s already done. In some cases, it continues to be an evaluation.” Akins referred to a report released in May by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), which suggested that compliance costs could be reduced by as much as $100 billion industry-wide if environmental regulators offered flexibility in complying with emission rules.

In the report, “Prism 2.0: The Value of Innovation in Environmental Controls,” EPRI examined the potential impact on the existing generation fleet of several current and pending EPA regulations:

- MATS rule with compliance by 2015.

- Clean Water Act (CWA) 316(b) for cooling water intake structures with compliance by 2018. (This was modeled as requiring closed-cycle cooling on facilities with intake flow of greater than 125 million gallons of water a day.)

- Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) regulation on coal combustion residuals with compliance by 2020. (This rule was modeled under subtitle D of RCRA, or as nonhazardous wastes.)

- Updated National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) on sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) by 2018.

The EPRI analysis found that installing a suite of new emissions controls would cost the U.S. economy up to $275 billion between 2010 and 2035 in present value terms if the current course is followed. EPRI said that by providing a flexible path, the overall cost could be reduced by $100 billion while achieving the same level of compliance.

A second major coal consumer—Southern Co.—also revealed it has recalculated its compliance costs. CFO Art Beattie told analysts the utility previously estimated its cost to comply with the EPA’s MATS rule alone could reach $2.7 billion between 2012 and 2014. Southern said that this amount could fall by anywhere from $500 million to $1 billion, depending largely on the number of baghouses in its final compliance strategy. “Based on our current analysis, our projection for MATS compliance for 2012 through 2014 now totals $1.8 billion, representing a reduction of $900 million from our previous estimates,” Beattie said in July. “While the number of baghouses has been reduced to four or five from a high of as many as 17, other costs have been added to our plan to reflect the need for additive injection systems and related plant modifications.”

He said the compliance plan also includes investments in transmission projects as well as fuel switching to natural gas. Southern’s resource plan now calls for approximately 13,000 MW of coal-fired generation to be “preserved.” Another 4,000 MW will remain “potential candidates” for retirement, while some 3,000 MW will use alternative fuels, primarily natural gas, for generating capacity.

Natural Gas Prices and Coal Unit Retirements

The recent economic competitiveness of natural gas complicates efforts to determine how much the EPA’s rules are affecting retirement decisions.

Progress Energy Carolinas, a newly merged unit of Duke Energy, said in late July it planned to accelerate retirement of one North Carolina coal-fired power plant previously slated for closure in 2013 and would retire the utility’s only coal-fired unit in South Carolina. The company said its 316-MW Cape Fear coal-fired plant in North Carolina and the 177-MW H.B. Robinson Unit 1 coal-fired plant in South Carolina would be retired Oct. 1. The decision to retire the 52-year-old Robinson coal plant was made due to pending changes in environmental regulations and other rising costs for smaller, older technology plants, the utility said. The cost of adding emissions controls on the small unit would run into the hundreds of millions of dollars. What’s more, the potential for additional emissions regulations would increase operating costs even further.

But the utility also acknowledged its decision was influenced by the anticipated early-2013 commercial operation of new natural gas–fired generation at the H.F. Lee Plant, continued low natural gas prices, and the success of the newly merged company’s joint-dispatch process that integrates generation operated by Duke Energy Carolinas and Progress Energy Carolinas.

Environmental rules also are affecting coal-fired power plants in the Upper Midwest. Wisconsin Power & Light (WPL) said in late July it will shut down three coal-fired units by the end of 2015. It also announced plans to add emissions control equipment on a Sheboygan generator, nearly doubling the $450 million WPL already is spending on emissions controls system-wide.

The utility’s plans include:

- Closing the two-unit, 200-MW Nelson Dewey power plant, whose units entered service in 1959 and 1962.

- Closing the 60-MW Edgewater Unit 3 generator, which entered service in 1951.

- Adding scrubbers to Edgewater Unit 5 to reduce SO2 emissions by about 90% a year.

WPL also said it either will close Edgewater Unit 4, which began operating in 1969, or convert it to burn natural gas by the end of 2018.

| Updated analysis. Key characteristics of coal-fired power plants in CSAPR and non-CSAPR states, including those slated for retirement. Sources: POWER and Burns & McDonnell |

||||

| Median MW | Median year built | Median capacity factor | Median heat rate (Btu/kWh) | |

| CSAPR state | ||||

| Unit has scrubber | 444 | 1974 | 67.7% | 10,066 |

| Unit has FGD | 411 | 1974 | 67.4% | 10,090 |

| Unit has SCR | 570.5 | 1973 | 68.4% | 10,045 |

| Non-CSAPR state | ||||

| Unit has scrubber | 383 | 1978 | 76.1% | 10,497 |

| Unit has FGD | 203 | 1968 | 64.0% | 10,355 |

| Unit has SCR | 241 | 1969 | 86.2% | 9,894 |

| CSAPR state, units for retirement | ||||

| All units for retirement | 125 | 1955 | 49.3% | 10,786 |

| Unit has scrubber | 117.5 | 1957 | 35.8% | 10,844 |

| Unit has FGD | 133 | 1957 | 42.0% | 10,807 |

| Unit has SCR | 212 | 1961 | 62.3% | 10,092 |

| Notes: CSAPR = Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, FGD = flue gas desulfurization, SCR = selective catalytic reduction. | ||||

Four years ago, WPL asked to build a $1.26 billion, 300-MW coal-fired power plant that could burn biomass for up to 20% of its fuel. State regulators rejected the proposal, however, calling it too expensive, and “foolish and irresponsible” in light of tougher greenhouse gas rules expected to be issued. As recently as July, WPL filed an application with its regulators to add SO2 scrubbers to Edgewater Unit 5 at a cost of up to $430 million (Figure 1). A decision from regulators on that proposal is expected next spring. If approved, the control equipment could be in service in 2016. The utility already is adding a NOx reduction system on Edgewater 5, as well as SO2 and mercury pollution control systems at Units 1 and 2 of the Columbia power plant. All told, WPL’s cost for those projects is $453 million.

In neighboring Minnesota, Rochester Public Utilities’ Board of Directors voted in early August to retire its Silver Lake plant in 2015. Its smallest and oldest unit began generating electricity in 1948. Three larger coal-fired units were added between 1953 and 1969.

“This is clearly an economic decision,” Jerry Williams, president of the city-owned utility’s board, was quoted as saying. “Basically, we can go out on the open market and purchase electricity… at a lot less cost.”

The retirement is “not surprising and not inconsistent with what utilities around the country are deciding to do with smaller, older coal-fired power plants,” William Grant, deputy commissioner of the state Commerce Department and head of its energy division, told a local newspaper. “They are determining that those facilities are so inefficient they are no longer economical to run, and continuing to do so would be detrimental to their customers.”

The plant must operate until late 2015 because of contracts to supply steam to Mayo Clinic and to generate electricity when needed by a regional power association.

In the Intermountain West, meanwhile, Black Hills Corp. said in early August that its Black Hills Energy–Colorado Electric and Black Hills Power units will suspend operations at some older coal-fired and natural gas–fired facilities this year. Colorado Electric’s 42-MW W.N. Clark coal-fired power plant (Figure 2) and natural gas–fired Units 5 and 6 in Colorado are set to suspend operations at the end of the year, according to a news release. Black Hills Power’s 25-MW coal-fired unit at the Ben French power plant in South Dakota was scheduled to suspend operations on Aug. 31, although the units still will be available to generate electricity when necessary.

In late July, Black Hills Energy–Colorado Electric filed an electric resource plan with the Colorado Public Utilities Commission. In the filing, the company proposed building a 40-MW simple-cycle, natural gas–fired plant, which would begin operating in 2016 to replace electricity produced by W.N. Clark. Colorado regulators last year rejected a company proposal to build an 88-MW natural gas–fired unit.

In Wyoming, meanwhile, Black Hills Power received a certificate of public convenience and necessity in late July to build the $237 million, 132-MW Cheyenne Prairie Generating Station, a natural gas–fired plant that will enter service in late 2014 and will replace capacity lost from the three coal-fired plants Black Hills Power is retiring.

The Role of the States

Analysis Group’s Tierney said the decision to close a generating unit often involves state regulators forming a triangle with the power generator and the EPA and state agencies in the other two corners. After all, in regulated power markets, electric power generators are granted certificates of “convenience and necessity” similar to the one Wyoming regulators granted to Black Hills Power to build its Cheyenne Prairie Generating Station project. This changes the dynamic from a two-way relationship between the utility and the EPA to a more complex three-way relationship that in instances of regulated markets includes state regulators.

In some circumstances, Tierney said, state regulators will apply a strict least-cost planning approach when deciding among options for generating units, which may include installing scrubbers, pursuing demand-side management strategies, or relying on market-based power purchases. She said that parts of the country that follow traditional regulatory approaches (such as the Southeast and the Rocky Mountain states) “play a huge role” in determining the types of investments their regulated utilities may pursue. By contrast, many states that are in the PJM pool, or in the Midwest (including Texas), operate competitive power markets, where power plant owners bear the responsibility of making business decisions on how best to comply with EPA regulations. “It’s much more a competitive market issue in those states,” she said.

Ron Binz, a former Colorado public utility commission chair and Denver-based public policy consultant, said the EPA’s current slate of rules represents the “last nail in the coffin” for many older coal-fired power plants. Key factors to consider in predicting which units are most likely to be retired include their in-service date, heat rate and unit efficiency.

Binz largely agreed with Tierney’s assertion that the role of state regulators in deciding whether or not a unit may close can vary widely and depends on factors that include market openness, the level of the regulator’s authority, and the willingness of the regulatory agency to exercise its authority. In Kentucky, for example, regulators lack authority to approve a utility’s integrated resource plan (IRP), the documents that are filed every few years and that lay out the utility’s plan for its generating mix. Binz said Kentucky’s utilities are on their own to pursue their IRP, and the commission’s authority is limited to reviewing whether the utility complied with its own plan. Other states, like Colorado, have broader authority to approve, disapprove, or modify a utility’s IRP. As an example, Binz cited Colorado’s action in 2010 to decide the fate of 2,000 MW of coal capacity based on projected EPA regulations. Those statutory limits and regulatory mindset figure in the latest round of generating capacity review triggered by the EPA’s 2011 Cross State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR) as well as MATS.

Characterizing Generating Units

Given that regulatory and business calculus, it’s possible to broadly characterize power plants that may be most vulnerable to shutdown decisions. This may be done via a relatively simple analysis to consider several critical factors. Before turning to that analysis, however, it may be useful to review the basics of CSAPR.

CSAPR (which was overturned in August by a federal appeals court) addresses emissions of SO2 and NOx from fossil fuel power plants in the eastern U.S. that contribute to downwind formation of fine particulate matter and ground-level ozone. The rule comes under Clean Air Act Section 110(a)(2)(D), which prohibits air pollutants from being emitted in an upwind state that “contribute significantly” to poor air quality in a downwind state.

The EPA announced the final CSAPR on July 6, 2011. It replaced the earlier Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR), which was remanded to the EPA in 2008 by the U.S. District Court of Appeals (D.C. Circuit). Although the D.C. Circuit remanded the CAIR rule back to the EPA, it did not toss it out. As a result, power plants have still had to comply with CAIR’s requirements as the EPA developed the replacement rule.

Last Dec. 30, the same D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals stayed CSAPR implementation—which was to have gone into effect Jan. 1, 2012—to give the EPA time to consider a range of lawsuits filed against the new rule. (As of this writing, the court had not yet ruled on those lawsuits.) In overturning CSAPR, the court kept CAIR standards in effect. At press time, the EPA had not said whether it would appeal the decision or try for a third time to craft acceptable regulations.

Analysis published last spring by the Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management concluded CSAPR did not significantly change the overall reduction requirements compared with CAIR, although it did limit the ability of individual power plants to meet their reduction requirements through interstate trading of emission allowances. While the D.C. Circuit rejected the original interstate trading approach laid out under CAIR, the now-overturned CSAPR regulation retained some ability for interstate trading.

With that understanding, the next step in our analysis is to consider at a macro level several key characteristics of coal-fired generating units located in the 27 states covered by CSAPR. The data source for this analysis is a comprehensive database of the physical and performance characteristics of all U.S. coal-fired power plants created by Burns & McDonnell and made available to POWER for this report. (An earlier analysis published in the May 2011 issue, “Predicting U.S. Coal Plant Retirements,” used this same database and may be found in the archives at https://www.powermag.com.)

The analysis presented here was done independent of Burns & McDonnell, was neither reviewed nor endorsed by the firm, and is structured as follows. First, it considers four factors for units that have scrubbers and are in states subject to CSAPR rules. Those factors are median nameplate capacity, median in-service date, median capacity factor, and median heat rate. Second, the analysis considers those same four factors but this time for units that have FGD and SCR equipment installed and are in CSAPR states. It then applies the same analysis to units that have scrubbers, FGD, and SCR controls in non-CSAPR states. Finally, it considers these same four factors for units whose retirements have already been announced. Summary results are presented in the table.

Among scrubbed units in states covered by the EPA’s CSAPR rule, the median in-service date is 1974, the median nameplate capacity is 444 MW, the median capacity factor is 67.7%, and the median heat rate is 10,066 Btu/kWh. Slight variations occurred for units that have FGD and SCR controls, with the largest difference evident in the median nameplate capacity among units that have SCR equipment. In that case, the median nameplate capacity increased more than 100 MW to an average of 570 MW. The capacity factor and heat rates among SCR-controlled units showed marginal improvements over other units in this category.

A different story emerged for coal-fired units in non-CSAPR states. Here there was little uniformity across the four factors that were considered. Scrubbed units had a median nameplate capacity of 383 MW, a median in-service date of 1978, a median capacity factor in excess of 76%, and a median heat rate of nearly 10,500 Btu/kWh. Units that included an FGD, by contrast, were smaller with a median nameplate capacity of 203 MW. These units also were around 10 years older, had a median capacity factor that was 12 percentage points lower, and a roughly comparable median heat rate. Finally, units in non-CSAPR states that were equipped with an SCR had a median capacity of 241 MW, a median capacity factor in excess of 86%, and a median heat rate of less than 10,000 Btu/kWh. By comparison, these units are workhorses and, despite their age, have benefited from capital investment to meet environmental regulations by enjoying high capacity factors.

A third story can be gleaned by examining generating units that are in CSAPR states and whose owners have already announced plans to retire them. These units tend to be small, old, relatively less efficient, and less-frequently dispatched. The data show these units have a median nameplate capacity of 125 MW, a median in-service date of 1955, a median capacity factor of less than 50%, and a median heat rate in excess of 10,750 Btu/kWh. Some of these units have environmental controls, but even here the units are small, old, less likely to be dispatched, and inefficient. Units slated for retirement that also have scrubbers had a median nameplate generating capacity of 117.5 MW, a median in-service date of 1957, a median capacity factor of 35.8%, and a heat rate higher than 10,800 Btu/kWh. Units equipped with FGD or SCR were slightly larger and had improved median capacity factors and median heat rates. Even so, they still were out of the running compared to units in the database not currently slated for retirement.

The fate of coal-fired generation remains fluid as owners weigh environmental rules, the effect of low natural gas prices, and the shifting cost of investing in emissions control technology. An analysis of generating unit data suggests that smaller, older, less-efficient, and less-frequently dispatched assets are most vulnerable to retirements. The recently accelerated retirement dates for some units indicates that economic factors are a more important determining factor than pending environmental mandates. What’s more, state utility regulators play an important—although varied—role in generating mix decisions as well as capital investments to comply with environmental regulations.

— David Wagman is executive editor of POWER.