In a move widely applauded by the power industry, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of the Army proposed a new definition of “waters of the U.S.” (WOTUS) that could exempt groundwater and ditches from regulation under the Clean Water Act (CWA).

The measures follow other recent significant regulatory actions by the agency. On December 6, the agency also announced proposed revisions to performance standards governing carbon dioxide emissions from new, reconstructed, or modified coal-fired power plants. On November 15, the EPA clarified guidelines on when activities can be grouped together to determine whether they trigger New Source Review (NSR) permitting. And on November 7, it posted a final implementation rule for the 2015 ozone standard.

A Narrow Definition for ‘WOTUS’

The revised definition for “WOTUS” proposed by the EPA and the Department of the Army on December 11 significantly narrows the number of waterways and wetlands that fall within the jurisdictional scope of the CWA compared to a contentious rule finalized by the Obama administration in June 2015.

The Trump administration’s proposed revised definition, for which the EPA will now accept comment for 60 days, encompasses: “traditional navigable waters, including the territorial seas; tributaries that contribute perennial or intermittent flow to such waters; certain ditches; certain lakes and ponds; impoundments of otherwise jurisdictional waters; and wetlands adjacent to other jurisdictional waters.” The baseline concept used to define WOTUS falls “within the ordinary meaning of the term,” such as, “oceans, rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, and wetlands.”

Significantly for the power industry, the proposal states: “not all waters are ‘waters of the United States.’ ” Specifically, it means the definition does not include features “that flow only in response to precipitation; groundwater, including groundwater drained through subsurface drainage systems; certain ditches; prior converted cropland; artificially irrigated areas that would revert to upland if artificial irrigation ceases; certain artificial lakes and ponds constructed in upland; water-filled depressions created in upland incidental to mining or construction activity; stormwater control features excavated or constructed in upland to convey, treat, infiltrate, or store stormwater run-off; wastewater recycling structures constructed in upland; and waste treatment systems.”

A Highly Contentious Rule

The final Obama-era rule, also known as the “Clean Water Rule,” granted the federal government broader powers to limit pollution. When promulgating the final rule, the EPA suggested that a pair of Supreme Court decisions in 2001 and 2006 made it unclear whether the act also covered smaller bodies such as groundwater, headwaters, streams, and wetlands that feed those larger waterways. The EPA also said that for more than a decade, it had received requests—from members of Congress, state and local officials, industry, agriculture, environmental groups, scientists, and the public—for a rulemaking that would clearly define and protect tributaries that impact the health of downstream waters.

But once the Obama-era rule was finalized, it quickly drew ire, amassing legal challenges by at least 31 states and 52 non-state parties, which argued that it violates the 10th Amendment’s federalism principles and that it exceeds the Constitution’s commerce clause. Among challengers were a number of electric utilities, which expressed concerns that water near plants, such as water drainage ditches and cooling ponds, may be considered U.S. waters. According to the Nuclear Energy Institute, the rule would create “significant practical problems” for companies operating nuclear power plants and planning new facilities. Similarly, the American Public Power Association suggested the final rule is problematic because it would drastically expand the WOTUS jurisdiction of EPA and the Corps, “which would subject more utility projects and activities to Clean Water Act jurisdiction.”

“If finalized as proposed, the new WOTUS rule would accomplish the Trump Administration’s goal of significantly scaling back the scope of federal jurisdiction under the agencies’ CWA regulations,” said attorneys from law firm Beveridge & Diamond. However, the firm noted the Obama rule is subject to extensive ongoing litigation. “In the meantime, inconsistency and confusion will continue over regulation of waters of the U.S.,” they projected.

Messy Legal Issues

At the heart of the rule’s messy legal issues are a 2006 Supreme Court decision in Rapanos v. United States. “Rapanos was a fractured decision in which the Supreme Court’s members issued five different opinions, including dueling opinions by Justice Kennedy and Justice Scalia. The 2015 WOTUS Rule was based largely on Justice Kennedy’s concurring opinion, which formulated a ‘significant nexus’ test for determining jurisdiction,” noted attorneys from Van Ness Feldman LLP on December 12. However, the proposed rule derives its key elements from Justice Scalia’s decision, “particularly its emphasis on the need for a direct hydrologic connection (rather than a “significant nexus”) for establishing jurisdiction,” they explained. At the same time, the proposed rule’s legal underpinnings are generally broadened, and it assimilates other Supreme Court decisions that interpret the CWA and the core concept of public navigability, they said.

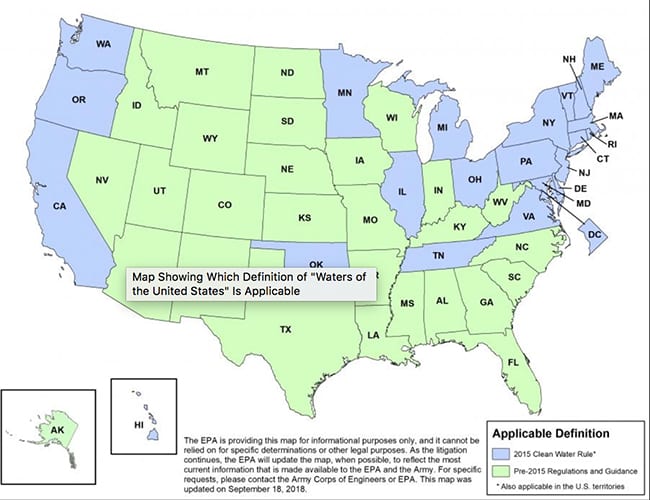

The legal wrangling began in October 2015, when a Sixth Circuit decision delayed the effective date of the Obama WOTUS rule pending judicial review. But the Supreme Court in January 2018 ordered the Sixth Circuit to lift its stay, among other actions. Then in August 2018, a federal district court in South Carolina issued an order that made the WOTUS rule effective in 26 states. However, in the months before that ruling, “as a precaution against the suspension rule being overturned, federal district courts in Georgia and North Dakota [had] issued orders … prohibiting the implementation of the WOTUS Rule in a total of twenty-four states while the courts consider the legality of the WOTUS Rule in full trials,” legal experts from law firm Troutman Sanders noted.

The EPA this week said that it is continuing to review the South Carolina district court’s decision, noting that it has filed motions appealing the order and seeking a stay of the decision. “While the litigation continues, the agencies are complying with the district court’s order and implementation issues that arise are being handled on a case-by-case basis.”

Despite the proposal’s legal issues, the Edison Electric Institute (EEI), an industry group that represents all U.S. investor-owned power companies, applauded the measure, saying the narrow definition provides more regulatory “certainty and clarity,” and “enhances opportunities to streamline energy infrastructure permitting.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)