Recognizing excellence in creative problem-solving to give a project new life and a new role, POWER magazine’s 2020 Reinvention Award goes to two gas-fired power plant construction projects completed simultaneously and by one team—ahead of schedule, and under budget—to bolster California’s energy transition.

The story about the remarkable reinvention of AES Corp.’s Alamitos Energy Center and Huntington Beach Energy Project sites began more than 60 years ago. In the era following World War II, Southern California’s population swelled in response to business and industrial development, and Southern California Edison (SCE), which built its first steam generation plant in Long Beach in 1911, capitalized on a steam generation capacity building frenzy in the region that ensued between 1950 and 1970. Among several plants it built in the 1950s and 1960s were the 2-GW, six-unit Alamitos Generating Station in Long Beach, and the 880-MW, four-unit Huntington Beach Generating Station in Huntington Beach, which was fully completed in 1967.

POWER POINTSWinning Attributes ✔ Giving new life and scope to two aging power generating sites that are crucial for a state’s own energy reinvention and local reliability. ✔ Improving the environmental attributes of the site by increasing efficiency, reducing emission rates, and eliminating ocean water cooling. ✔ Using an innovative project management approach to simultaneously complete the projects with the same teams. ✔ Safely completing both projects months ahead of schedule and under budget. |

In 1998, following restructuring of the electric industry, AES subsidiary AES Southland bought the Alamitos and Huntington Beach power generation facilities (along with another plant in Redondo Beach). Both plants have since repeatedly proven to be crucial to regional supply reliability. Though refurbished in the aftermath of the 2001 California energy crisis, Huntington Beach Units 3 and 4, for example, were eventually retired in 2012 but brought back to play a pivotal, albeit temporary, role to ensure regional supply after the now-shuttered 2,150-MW San Onofre nuclear power plant in Southern California was abruptly taken offline, owing to steam generator issues. And while Huntington Beach Unit 1 was retired in December 2019, and Unit 2’s retirement is scheduled for December 2020, Unit 2 may receive a short-term permit extension to operate past 2020 for reliability reasons, as AES Project Director Matt Dugan told POWER in May. Meanwhile, though three of the six units at Alamitos were shuttered in December, and the other three are set to close at the end of this year, these, too, could receive reprieves until 2023.

As Dugan explained, environmental considerations drove AES’s initial proposal in 2012 to modernize both Alamitos and Huntington Beach, and give them a new role in California’s own energy reinvention. In a bold measure rooted in decades of eco-pioneering, the state set the first economy-wide greenhouse gas (GHG) limit in the Western Hemisphere in 2006, kicking off now-codified ambitions of producing 100% of its power with zero-emissions energy sources, and effectively limiting out-of-state coal power. In 2010, meanwhile, the State Water Board adopted stringent technology-based standards that required several plants—including Huntington Beach and Alamitos—to cease once-through cooling.

“The real estate was valuable to the grid,” Dugan noted. “We wanted to take advantages of our access to the grid but be able to put a much more efficient plant in place.” Because initial planning began nine years ago—at a time when renewable energy’s intermittency was a major concern—AES chose to go with natural gas. The two plants that went online in January may be “the last gas-fired plants built in California,” Dugan said, but they still have a crucial role to play: “AES’s philosophy from the beginning has been to put in place generation that would maximize the utilization of renewable energy,” he said.

Two Plants, One Approach

Though AES received a project license for the Huntington Beach project from the California Energy Commission (CEC) in 2014, it amended it in 2017 to reflect newer technology. AES’s most important move was perhaps to award Kiewit the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contracts to build the two separate 650-MW combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) projects under similar timeframes, Dugan noted.

Kiewit, which AES had never worked with before, won the competitive bid mainly because it had a good history of building projects in Southern California; understood California’s regulatory environment, labor, and work issues; and it had a strong relationship with the Building Trades, Dugan said. “At one point, we actually thought maybe we would contract with two separate contractors for these sites, which are 13 miles apart. I can tell you that I’m glad we made a decision to contract with a single company, because it brought a lot of synergy to the two projects,” he said.

Kiewit told POWER its success in bringing both projects online months ahead of schedule and under budget—for Huntington Beach, it was eight weeks ahead of guarantee, and for Alamitos, it was a stunning three months—hinged on the company’s ability to capitalize on the similarities. Both projects feature GE 7FA.05 gas turbines in a 2 x 1 configuration. AES chose the technology for its proven fast-start and rapid-response capabilities. Additionally, the equipment for both projects—including heat recovery steam generators, air-cooled condensers (ACCs), steam turbines, and more—was also the same.

In a notable first for Kiewit—a company that has a long legacy of project construction—it achieved this in part by having the same team deliver the engineering for both projects simultaneously. Also especially telling about the existing synergies between the sister projects is that they were managed by two Kiewit mechanical engineers who are married: Pegah Skarsgard, Huntington Beach project manager, and Brock Skarsgard, Alamitos project manager. For their part, the Skarsgards told POWER that the “two projects had a strong client partnership, great skill and talents across all employees, growth in training and development of our people, strong vendor relationships, successful schedule, great budget performance, and lastly a top-notch record in quality and safety in this industry.”

|

|

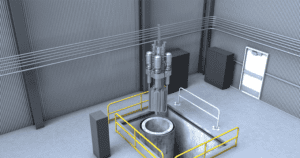

1. Both the Huntington Beach and Alamitos projects were engineered by the same Kiewit team, which fluidly moved lessons learned from project to project. This unique approach led to refined engineering processes, including holding common pre-design conferences and using one 3D model for both plants, and, ultimately, to completion months ahead of schedule. Courtesy: Kiewit |

Diligent planning was integral to get it done (Figure 1). Kiewit Project Manager Dan Rocole led the combined procurement buyout as soon as the projects were kicked off in January 2017. “This required close collaboration of the engineering and procurement teams with suppliers to stagger shop drawings, first getting approval for Huntington Beach before submitting the same scope drawings for Alamitos,” Kiewit said. The projects, which also shared management resources, strategically staggered construction of the ACCs. ACCs, which are “direct dry-cooling systems where steam from the steam turbine exhaust is condensed inside air-cooled, finned tubes,” are a notable aspect of the projects because they eliminate the need for ocean water. To ensure their construction was efficient and cost-effective, for example, Pegah Skarsgard led the ACC work at Huntington Beach six months before Alamitos attempted it, and then she transferred to Alamitos to complete that project, beating both budget and schedule—and “breaking existing ACC cost and schedule records companywide,” said Kiewit. For her leadership at Huntington Beach, this January she snagged the Peter Kiewit Award for excellence in management—Kiewit’s most prestigious award.

A Restricted Schedule

Despite their similarities, the projects’ joint construction wasn’t easy. One specific challenge highlighted by Pegah and Brock Skarsgard was an initiative to design both projects with the same engineering design team. “The physical project sites were different in footprint size, so that had to be taken into consideration during engineering to ‘leverage’ the same design,” they explained. “The outcome was that the ‘powerblock’ portion of both projects was identical both underground and above ground. The steam turbine generator, balance of plant areas, and the ACC were [a] different design due to this different footprint.” To address this, Kiewit engineers changed the plant and model coordinates on Huntington Beach to match Alamitos for design purposes. “Our engineering and constructability team did [an] excellent job optimizing both projects to be both efficient and productive for construction and still meeting our clients desires in maintainability and presentation to the public,” the project managers said.

As Dugan pointed out, meanwhile, Huntington Beach is nestled between a residential area and a beach, and Alamitos is in an industrial area—and both had operating units onsite while construction was underway. Huntington Beach’s small footprint proved so challenging that AES had to relocate one of the 230-kV high-voltage lines to allow Kiewit to keep building. Along with careful management of plant output and grid stability, the plant location also meant spot-on logistical planning to get equipment from all around the world to the site. Overall, a total of 64 heavy-haul permitted loads and a total of 8,000 equipment and bulk material deliveries were made to both sites—with zero incidents or events. Finally, noise management, especially at Huntington Beach, was also a “very big consideration,” owing to noise restrictions, Dugan said.

Kiewit tackled potential noise and light disturbances by restricting hours of construction to the daytime, the Skarsgards said. That meant the 33-month schedule was “always a focus during the projects. With limited nighttime construction allowed during the projects, the teams had to ensure we were progressing on or ahead of schedule,” they noted. “Our engineering team did an excellent job getting [issued for construction] drawings out on or ahead of schedule, and we worked very closely with our vendors to ensure no late equipment deliveries were expected. Our construction team worked hard to make outstanding unit rates and be as efficient as possible during execution to gain even more schedule.”

Dugan lauded these achievements, but he highlighted yet another one: “I think the biggest point from this is that every large movement on these constricted sites had to be very carefully planned to make sure it didn’t impact operations or safety of the folks doing the work. I’m very proud of this,” he said. “We’re now at 3.7 million job hours of safe work [with no lost time incidents] between both projects. And that is because Kiewit brings a great safety culture to the work, and they communicate—very clearly and consistently—what their expectations are, and behave in a way that supports their talk.” ■

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor.