Two more U.S. nuclear power plants are facing early retirement, joining a string of generators whose fate was determined by market conditions, political pressure, or financial stresses assailing the sector. Several others may be poised to join them.

The 647-MW Duane Arnold nuclear plant in Palo, Iowa, will likely close in 2025 after a current contract with the facility’s primary customer expires, said NextEra Energy Resources’ chief financial officer, John Ketchum, in a fourth-quarter earnings call on January 26.

“Without a contract extension, we will likely close the facility at the end of 2025 despite being licensed to operate until 2034,” Ketchum said. “As a result, during the fourth quarter, Duane Arnold’s book value and asset retirement obligation were reviewed, and an after-tax impairment of $258 million was recorded that reflects our belief it is unlikely the project will operate after 2025.” Ketchum added, however, that NextEra will continue to pursue a contract extension.

On the same day, the Toledo Blade reported that FirstEnergy Corp.’s Davis-Besse nuclear plant in Oak Harbor, Ohio, is headed for premature closure, citing James Pearson, the company’s chief financial officer. Pearson told the newspaper that no date has been set for the closure of Davis-Besse. He also reportedly said that the outlook for the company’s Perry plant in Ohio and twin-reactor Beaver Valley nuclear plant in Pennsylvania is “bleak.” FirstEnergy is intent on exiting its competitive business, but though the company may want to sell the plants, they are “probably impossible to sell in today’s market,” he reportedly said.

A Critical Condition

The plants join a series of generators recently stricken by financial pressure primarily by competition from cheap natural gas, expanding renewable capacity, and lethargic power demand growth.

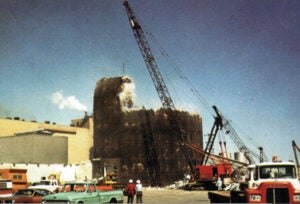

Throughout the short history of the U.S. nuclear power sector, 31 reactors licensed to operate have been permanently shut down—11 between 1960 and 1980; four in the 1980s; and nine in the 1990s. The recent streak began in 2010—12 years after the nation’s last reactor, Millstone 1 in Waterford, Connecticut, had been shut down in 1998—as Exelon announced it would shutter its Oyster Creek plant in New Jersey by 2019 owing to economic conditions and changing environmental regulations. In February 2013, Duke Energy (then Progress Energy) retired its Crystal River reactor in Florida, unable to repair damage to the containment structure. A string of casualties then ensued, as Kewaunee in Wisconsin was closed in May 2013; two units at San Onofre in California were formally shuttered in June 2013; Vermont Yankee in Vermont was shut down in December 2014; and Fort Calhoun in Nebraska closed its doors in October 2016. Other units slated for near-term shutdown include Pilgrim in Massachusetts and Palisades in Michigan. (For more, see, “THE BIG PICTURE: Nuclear Retirements.”)

Early retirement has also been proposed for Clinton and Quad Cities in Illinois and for Nine Mile Point, Fitzpatrick, and Ginna in New York—but their fate appears dependent on the outcome of legal challenges to “bailout” programs to keep those plants operating for economic reasons. The states’ measures are being legally challenged by several independent power producers—including Dynegy, Eastern Generation, NRG Energy, and Calpine Corp.—and, prominently, competitive power producer trade group the Electric Power Supply Association. The consortium has long argued that the state rules interfere with Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) jurisdiction over wholesale electric rates and unlawfully interfere with interstate commerce.

In January, FERC, an independent regulatory government agency that is officially organized as part of the Department of Energy (DOE), thwarted a DOE proposal to require independent system operators and regional transmission organizations to establish “just and reasonable” rates for resilient and reliable plants, such as coal and nuclear baseload generators. The regulatory body has since queried grid operators in a new docket on what defines resiliency and sought their input on how it can be measured.

Meanwhile, state subsidies are also under consideration in Connecticut, where Dominion, the owner of the Millstone 2 plant, though profitable, has argued it will need incentives to help the state meet long-term economic and environmental goals. In Pennsylvania, a nuclear caucus—convened March 2017 as the first of its kind in the nation—has specifically advocated for keeping open Exelon’s Three Mile Island. In New Jersey, a bill to help keep open Hope Creek and Salem will be voted upon by a state Senate committee on February 5.

Earlier in January, California regulators approved Pacific Gas & Electric’s application to retire the Diablo Canyon plant by 2025, following a protracted battle over the generating station that pitted local economic interests against environmentalists and other opponents of nuclear power. In New York, political pressure combined with economic misgivings, also prompted plans to shut down Indian Point by 2021.

A Swath of Other Reactors May Be Troubled

According to a September 2017 report from the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), several more nuclear plants are likely to retire early, stymied by an “ongoing industry wide, systemic economic and financial challenge to operating nuclear plants particularly in the deregulated markets.”

A revenue gap analysis conducted by the national laboratory for 79 of 99 operational reactors that are in a region where public wholesale electricity market prices are available suggests that 63 units would have lost money in 2016. Of those 63, 36 are merchant generators, 19 are regulated, and eight are public power generators.

INL suggests that among plants at high risk of early retirement are Davis-Besse, Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, and Xcel Energy’s Prairie Island in Minnesota.

A number of studies separately suggest similar findings. A working paper from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research released in March 2017, for example, suggests that about 21 GW in merchant deregulated markets are retiring, or are at high risk of retiring. (For more, see “THE BIG PICTURE: Nuclear Financial Meltdown.)

Another factor complicating soaring retirement numbers: More than 80 commercial reactors have garnered federal licenses to operate for 60 years—but more than half of these are more than 40 years old.

The Reliability Debate Smolders

Concerns about these retirements are founded on a widely touted premise that the collective loss of this baseload power could affect electric reliability and resiliency. The Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI), echoing trade groups that lobby for other fuel sources including coal and gas, has said that a key factor for several premature retirements is the failure of RTO markets to value attributes of nuclear power. Complicating this is that unlike other power plants, nuclear plant closures are permanent, as there is no established regulatory process to reverse the decision, the NEI says.

In December, however, the North American Electric Reliability Corp. (NERC) suggested in its 2017 Long-Term Reliability Assessment that power generation from natural gas–fired units and renewable sources such as solar and wind will provide enough electricity to offset closures of coal and nuclear plants over the next decade, at least.

But at a hearing at the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on January 23 in which much of the discussion was centered around how power reliability fared during the recent record-breaking cold weather event in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, a number of key stakeholders noted that nuclear was as vital as other baseload plants in maintaining reliability.

“During this recent cold weather event, obviously more than half of the total supply was coal and nuclear,” President and CEO of PJM Interconnection Andrew Ott testified. “We couldn’t survive without gas; we couldn’t survive without coal; we couldn’t survive without nuclear; we need them all.”

Ott also noted, however, that pricing doesn’t always reflect performance and availability. “Therefore, when they go sell their energy forward, the fact that they were on reliably during the cold weather isn’t reflected in the price. That’s unfair, it puts them at a disadvantage and we need to fix it.”

Newly installed FERC Chairman Kevin McIntyre testified that while the regulatory body was still receiving information from ISOs and RTOs regarding the cold weather event, the bulk power system appears to have performed relatively well, and most RTOs/ISOs had sufficient reserves to ensure reliable operations. During the cold snap, only MISO and NYISO experienced reserve shortage events, he said.

McIntyre also suggested, however, that system-wide reliability may have been achieved because several regions were prepared. “In MISO, for example, a Cold Weather Alert directs generators to implement winterization plans for plants, ensure the availability of staff to operate plants if called on, double-check fuel supplies, and defer maintenance on generators and transmission lines, if possible,” he said.

“As the cold weather settled in and the risk to reliability increased, RTOs/ISOs issued Conservative Operations Notices and Watches. These notices suspend maintenance on generators and transmission facilities so that they may be available, if needed. These notices also permit out-of-market actions to relieve system constraints.”

Among notable events during the cold snap was that a transmission line connecting the Pilgrim nuclear plant to the New England grid tripped, requiring the plant operator to manually remove the plant from service, McIntyre said. In PJM, gas supply issues caused outages at certain generation facilities, “but mechanical problems and other factors caused significantly more outages across all types of generation facilities,” he said.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)