Power generators have always had to make afetyome changes as each new generation enters the sector, but today’s new workers are bringing with them attitudes and skills that challenge traditional plant management, for good and ill. Here’s what some companies and plants are doing to make the best use of younger workers while getting them to work efficiently alongside older generations.

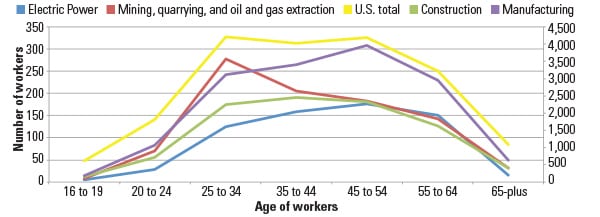

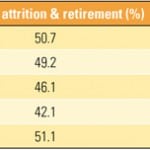

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median age of workers in the electric power generation, transmission, and distribution sector in 2015 was 45.7. This figure is higher than the U.S. average (42.3) as well as median figures for mining (40.8), manufacturing (44.4), and construction (42.7). Of the total 661,000 workers in the electric power sector, 502,000 are 35 or older, 343,000 are 45 and older, and 166,000 are 55 and older.

Those numbers are likely no surprise to those in the field, where the challenges of an aging workforce have been an oft-remarked-upon issue (see sidebar). While some industrial sectors such as mining and construction have been able to attract younger workers, the power sector has traditionally skewed older (Figure 1). There are many reasons for this, among them, the facts that more extensive training is often required than for other professions and that many workers enter the power sector after sometimes-lengthy careers in the military (see “Veterans Bring Needed Skills to the Utility Industry” in the June 2014 issue).

Tom McDonnell, power generation industry leader at Rockwell Automation, who spoke to POWER by email, laid out what this means.

“Generators,” he said, “face the loss of critical knowledge and the inability to find skilled workers with power generation–specific skills. An aging workforce—coupled with increasing customer demand, decreasing generation rates, rapid technology innovation, and renewable integration—means that the power generation business and utility business landscape will evolve significantly over the next fifteen years,” he said. “While younger generations of workers will bring new skills to the industry—particularly in modern technology—it is crucial for generators to tap into the knowledge and expertise of seasoned workers.”

Further, he noted, “Generators must contend with both aging technology and the retirement of the coal fleet. The personnel in aging power plants are being asked to do more with less resources to maintain productivity. Owners of these plants feel the squeeze and are strategically implementing automation to augment the reduction in personnel.”

But those younger workers are coming one way or another, and the power sector needs to be ready. One less-noticed trend is that, between the need to keep experienced older workers around longer and more-frequent delays in retirement, the U.S. will for the first time have five different generations working alongside each other. The BLS first anticipated this trend a few years ago, and the 2010s are when it was first seen as the youngest workers enter the workforce while the last few pre–Baby Boom workers remain on the job.

What will a five-generation power plant look like, and how do plant managers make it work? POWER talked to a variety of individuals in the sector to see what’s ahead.

Attract the Right New Workers

Successfully integrating younger workers begins with attracting people who have honest interest in the field and realistic expectations about what it involves. Several people POWER talked to lamented the impression many young people have of power generation as stodgy and old-fashioned, which they say isn’t accurate.

“It’s hard to attract people to fields that are characterized by repetitive work, especially if it is seen as not transferrable experience,” noted Bob Ashenbrenner, vertical solutions architect at mobile technology firm Xplore Technologies. “Fortunately, much of power generation work is transferrable. There are multiple fuel sources, plus wind and solar, all of which use part or most of the same skills. Many large industrial sites also generate their own power. So it is accurate to say that a job in any power plant can lead to a career in power, whether it’s at a large-scale site for a utility or in a smaller setting where the same skill set is relevant.”

What’s more, the technology in most power plants is advancing rapidly, and workers looking for high-tech careers should be made aware both of the many opportunities and that their interests and skills are badly needed (Figure 3).

|

|

3. Cross-functional. While younger workers may be attracted to power sector positions in renewable energy because they are perceived as more environmentally friendly, they should be aware that many skills are transferrable across the industry regardless of the generation source, making transitions from one field to another fairly straightforward. Courtesy: Duke Energy |

“Utilities’ recruitment and retention are going to be driven by the extent to which work responsibilities can transition from technician to information worker to better align with expectations of today’s workers—across many generations,” Ashenbrenner said. “Younger workers especially have come to expect always-connected devices that are touch and voice accessible.”

Ashenbrenner recommended downplaying traditional job marketing and playing up the importance of power generation to modern technologies.

“Rethink how you describe and market the job: The job isn’t ‘power plant.’ It is ‘maintaining conditioned power networks.’ Virtually every machine and device in every industry uses energy—that’s powerful to a younger worker who wants to ‘make a difference.’ But don’t just make the description moralizing. Connect it to a career. Present the impact of their job on a larger scale.”

Fran Sullivan, senior vice president of operations for NRG, explained how the giant generator makes an effort to cultivate an image distinct from how younger workers may view traditional utilities.

“We constantly look for ways to improve how we generate electricity,” he said. “Customers see NRG as innovative, offering technologies for the home and for businesses that are being adapted to improve efficiency and reduce environmental impact. The lesser-known fact is that we employ that same methodology to our fleet generation. When you see that the company is tackling that impact issue on both ends of the spectrum, it says a lot about the commitment to making change.”

With more and more private companies—particularly high-profile tech firms like Google and Amazon—getting into self-generation, generators can make clear to younger workers that generating electricity doesn’t mean a lifetime of being tethered to a turbine or boiler.

“Workers don’t want to be locked into one job or one field,” Ashenbrenner said. “A programmer working at Twitter knows that her skills translate to thousands of other employers and that having Twitter on her resume adds to her value. Power plants can offer the same appeal: Transferrable experience. A resume at a power plant, especially if it includes some information worker tasks, prepares for a career with fossil fuels and renewables, with large-scale utilities and local power subsystems.”

Get Past the Stereotypes

If you listen only to media stereotypes, you may be concerned that your youngest workers will arrive with smartphones surgically attached to their arms, expecting to be promoted to CEO their second week on the job. The reality, according to recent research in Harvard Business Review (HBR), is that a 25-year-old worker nowadays has more similarities than differences with 25-year-old workers 30 years ago. Desires to make a positive impact on their organization, do work that has beneficial effects on social and environmental challenges, and be passionate about their job have not changed substantially across generations.

Nevertheless, today’s younger workers do approach their jobs differently than today’s older workers in some respects. “Younger workers tend to seek work that supports their chosen lifestyles, while older workers choose lifestyles that their work supports,” Steve Ludwig, Rockwell Automation’s safety programs manager said. “Younger workers are no longer attracted to low-tech, dirty, manual jobs in remote locations simply for the money. They want to live and work in more urban environments, in a clean, creative setting.”

But as an article in HBR suggests, managers are usually better off focusing on similarities rather than differences in order to help build collaborative relationships between older and younger workers. Today’s younger workers are especially receptive to discussion, engagement, and group activities that can help with knowledge transfer and mentoring.

Tammy Ridout with American Electric Power (AEP) says the big generator makes a deliberate effort to build these kinds of cross-generational teams.

“Through the introduction of ‘lean’ processes and meetings in our plants, employees have found themselves in problem-solving groups with people from a wide variety of backgrounds,” she said. “During those events, the value of both the younger and more experienced worker is usually revealed. They both bring important perspectives to the table and, although they don’t always realize it, they build on the talents of each other to generate a better final product than if either had taken on the task independently.”

McDonnell noted this is an ideal way to engage younger workers.

“Younger workers have high expectations of the workplace and want to be part of decision making processes,” he said. “This requires utilities to reassess business processes, the utilization of new technology and the ability of real-time information to enable faster, better decisions.”

Making Technology Transitions

Ridout noted that, not surprisingly, younger workers tend to be more adaptable to technological evolutions.

“Younger employees seem to be more flexible to changes, especially where technology is concerned. Controls automation, upgrading software programs, or migrating to performing tasks like registering for benefits online seem less of a burden on Millennials.”

But while older workers may need different approaches to adapt to new technologies, the stereotypes of Baby Boomers befuddled by their smartphones and computers don’t really translate well to the power sector.

“Today’s older employee has migrated and moved with the technology throughout the last 30 years, from pneumatic and relay-based controls to the early microprocessor controls such as the PLC2 and PLC3 to a modern DCS like PlantPAx,” McDonnell said. These workers understand electronic processes and the advantages of digital controls and shouldn’t be patronized (by managers or vendors) when new tech is introduced (Figure 4). “The biggest difference between generations in the use of power industry technology is the fact that new workers prefer mobile platforms and handheld technologies to transfer information.”

|

|

4. Mobile tech. Both older and younger workers can benefit from a transition to mobile technology for plant functions. Don’t assume older workers will resist the change or will be more challenged by it than younger ones. Courtesy: XPlore Technologies |

Still, new tools may need to be introduced differently for older workers, without assumptions about worker familiarity or desire to change platforms.

“An initial introduction with a more hands-on instructional follow-up, by a live instructor, is often helpful to adapt older workers to the new processes,” Ridout said. “We share information through electronic versions as well as bulletin boards and tailgate talks to satisfy those who crave instant information as well as those who need a more personal delivery method.”

Sullivan noted that many changes can actually make things easier for older staff.

“We find that the knowledge and experience of more-tenured employees is a benefit to making improvements in our plants,” he said. “Over time, power generators have implemented innovative approaches that minimize labor-intensive tasks and reduce workload. This continuous improvement process has been primarily in the interest of improving employee safety and efficiency, but also has the effect of improving processes such that all workers have less–labor intensive tasks.”

One key difference, Ashenbrenner noted, is that older workers are less enamored of making changes just to get the latest gear—they want clear justification for the new approach.

“Older workers tend to question the benefits of too many new technologies,” he said. “They’ve relied on the same paper-driven processes for decades and, in their experience, the way they’ve done things has always ‘worked.’ They believe that they can continue to work as before without issue.”

There are differences of opinion on how much this attitude should be accommodated, however.

Ashenbrunner said the key is making the transition as seamless as possible. “Make the on-screen forms and tools as similar to existing processes as possible. Even let the older technician type in the number under the barcode on the equipment if he chooses. After a while, he’ll try the scanner, see how much easier it is, and then switch on his own.”

But John Roffel, product line director–simulation and competency for Honeywell Process Solutions, thinks this is the wrong approach. “It’s amazing how often we duplicate the old analogue view and interaction in the new digital world, only to accommodate a significant resistance to change. Compromise equals risk, so this resistance is indeed important to overcome for the benefit of all.”

Roffel suggested that generators “should adapt for the benefit of all generations as most things that would benefit an older worker are also beneficial for the rest. What is more problematic is the resistance to change from the older generation, which has left an industry that some consider as obsolete. This resistance has resulted in compromise as new technologies (such as human-machine interfaces) are deployed.”

Managers who have done a good job building intergenerational bridges can leverage them when there’s a technology transition, Sullivan noted.

“We focus a great deal of energy around teamwork,” he said. “By taking advantage of everyone on the team, we see more-experienced workers sharing knowledge with newer workers, while newer workers share ideas and their own experience with technology with workers who may not be as tech savvy. This knowledge sharing is especially important since our fleet is very large. Regardless of background, our view is that when one of us needs help, we all are accountable to jump in and assist.”

McDonnell agreed. “Generations can complement each other,” he said, “with younger workers providing insight to newer technologies, and older workers providing insight into the effect of technology on physical equipment.” Generators, he said, “can manage the challenges effectively by providing technology with traditional and remote capabilities, as well as training opportunities. This broad, cross-selection of resources allows workers to learn in a matter that is most effective to each individual.”

Remote technologies are particularly well suited to bridging generational divides, McDonnell noted.

“Remote access allows a plant’s most seasoned employees to offer their expertise to sites around the world from a central location,” he said. “In addition, enabling workers to remotely monitor the operations of an isolated location, for example, can help attract and retain younger workers who want to live in a metropolitan area versus near the plant.”

All that being said, there are older workers who may have trouble with new technologies, and managers should avoid making assumptions about their experiences.

“There are workers who do not have PCs at home, or if they do, someone else maintains it for them, usually one of their children,” Ashenbrenner said. “So introducing mobile technology into fields like power plants means that some of the employees are first-time computer users.”

Training Options

Roffel stressed that different generations may need different training approaches because their educational experiences before arriving on the job can be very different (Figure 5).

|

|

5. The digital future. Younger workers are most familiar with online and interactive education, but all workers can benefit from advanced training technology with the right approach. Courtesy: Honeywell |

“Today’s generation of young people entering the industry have been conditioned by their experiences with gaming, the Internet and mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets, to expect a different type of learning experience,” he noted. “They expect interactive and engaging activities, to capture their attention. They need immediate feedback as a means to motivate, and they are well versed in accepting training on demand.”

This isn’t necessarily true with older generations, however.

“We know from research studies that an effective training program for both older and next generation workers uses a variety of techniques to improve the effectiveness of training and in particular the higher order skills needed by such workers. For example, the ability to evaluate adequacy of information and procedures upon which conclusions and decisions are based, is key for process operators. So, too, are problem-solving skills, and the thought processes involved in analysis, comparison, interpretation, and evaluation. All are central to the role of process operators.”

But this is not to say that generators should set up entirely different training tracks for different generations.

“This is the crux of the issue that has made the transition to the next generation so difficult. It is enough to accept that there are differences, but it is necessary to evolve,” he noted. “The older worker needs to adapt and learn new and better ways to get the job done, safer and better. A culture of continuous improvement must be aligned with an evolution and adaption of appropriate emerging technologies.”

Safety Matters

One issue that came up repeatedly was safety. Younger, less-experienced workers need time to adopt good mindsets and fully understand an organization’s safety culture, and they may not immediately appreciate that “the way we’ve always done it” is the rule for a reason. “Safety procedures, culture, and processes do not change regardless of the employee’s generation,” McDonnell said.

And yet, the understanding of what makes a safe workplace continues to evolve (see “New Thinking on Old Safety Issues” in this issue and “Best Practices for Aligning Safety Metrics, Incentives, and Performance” in the February 2015 issue). Safety professionals recognize that a willingness to challenge established procedures can lead to improvements in safety, and “new eyes” can sometimes see risks that older ones have overlooked. In training new workers to the plant safety culture, care needs to be taken not to usurp workers’ responsibility to keep themselves safe.

In addition, safety risks for older and younger worker are often not the same.

“Younger workers tend to have more injuries due to inexperience, underestimation of risks, and unwillingness to ask questions,” Ludwig said. “By contrast, older workers tend to have more musculoskeletal and repetitive stress injuries due to years of wear and tear on their bodies.”

A recent Rockwell Automation white paper stresses that generational issues need to be taken into account in safety planning and plant design.

“Older workers require physically less-strenuous interaction with machinery, including reduced lifting, bending, twisting, and repetitive actions. Younger and inexperienced workers require more passive safety systems to help mitigate risks in the event of an inappropriate action, such as placing a hand or another body part in a hazardous position,” it notes. “Hazard assessments should take into account not only the traditional hazards, but also ergonomic and usability issues for a broad range of workers. Engineers performing assessments, building functional specifications and designing machinery need to assess all potential operator and maintenance technician movements as part of the process.”

Changing Career Arcs

One challenge of managing the Millennial generation is its reputation for wanting to move up faster and move around more. While this is a stereotype, it has some basis in reality.

“This is true, and we do see it,” Ridout said of AEP. “We try to have a variety of different assignments for employees where they can stay challenged with meaningful work. We are fortunate that we are a large corporation, and we always have internal job postings to fill vacancies. Employees looking for a change aren’t held back, and if they are the successful candidate for a job opening, they can transfer to a new group to keep learning something new.”

Sullivan reported much the same thing for NRG.

“The main difference that we see is that younger workers today are much more focused on professional development. Once they are assigned to a plant, it may be some time before their talents are recognized outside that setting,” he noted. “To address this, we’ve established special programs that team up young employees with senior management. One example is our Women in Power initiative. Since women have historically been under-represented in our business, we want to make sure that they get good development opportunities outside of their current roles. Our program gives mentees direct access to senior leadership from across the country. This gives them exposure across our fleet, increases their experience, and accelerates their growth opportunities.”

While this requires a shift from traditional practices of having the same workers staffing a plant for decades to retain institutional skills, it can still be a benefit to a company that stays flexible.

“We don’t look at this as turnover, even though a certain department may lose a worker,” Ridout noted. “That worker who transfers is a valuable asset to AEP and is becoming more valuable by learning a new job in a new department and becoming well-rounded in many facets of our organization.” ■

— Thomas W. Overton, JD is a POWER associate editor.