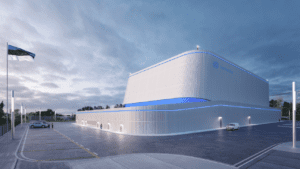

When asked to imagine a power plant, most people’s mental images don’t include families dangling fishing poles into cooling ponds or kids moving among educational displays that explain alternative forms of energy generation. But that’s exactly the scene that’s unfolding at Faribault Energy Park, the newly opened combined-cycle plant in southern Minnesota (Figure 1).

1. Picture perfect. Aesthetic appeal was an important consideration in the design of Faribault Energy Park that resulted in including oversized tinted windows, stone facing, and attractive landscaping. Courtesy: Avant Energy

The result of such features has been a decidedly welcoming attitude from city officials, the citizenry, and the media in Faribault, Minn., a town of 22,000 less than an hour from the Twin Cities of Minneapolis/St. Paul, which influence the town’s attitudes and media.

The warm reception wasn’t unexpected. As project developers, we took very specific steps to ensure that we secured community buy-in throughout the process. Although our business objectives were to generate efficient, affordable power, we strongly felt that we could do so while generating support from the host community.

At Faribault Energy Park, we were able to avoid the controversy that is often associated with power plant siting, construction, and operations. Our experience could help you build on time and on budget.

Not in my back yard

The familiar NIMBY (Not in My Back Yard) factor is an everyday irritant in the plant siting business and frequently stops projects in their tracks. Everyone in the power industry knows how opponents, contrarians, or activists from within (or beyond) the community can affect a project either through the courts or by tipping public opinion against a project. Even a mild delay will decimate a project schedule, increase construction costs, and even cause a regulatory body to hesitate before granting an approval. In the extreme, project delays have been known to cause investors and owners to cancel a project.

Opponents can make life extremely uncomfortable for facility developers. One opponent to a plant in Ohio described the proposed facility in memorable terms as “a toxic millstone around the neck of the community.” A critic of a Massachusetts plant was quoted as saying, “By its very nature, the plant would bring harm to the city.” Opponents know how to strike a blow, don’t they? These criticisms were aimed at well-designed, technologically advanced plants, but hyperbole that’s not held to a standard of truth has caused considerable delays to and cancellations of many projects. The NIMBY scenario has played out in every region of the country and around the world.

Then why, in Minnesota, was our plant’s grand opening attended by approximately 5,000 people from throughout the region? Why were families willing to spend part of a sunny fall Saturday at a power plant? Why did city officials cheerfully and proudly participate in the ribbon-cutting at a community celebration?

First and foremost, it’s because we developed a facility with an appealing package of environmental and community benefits. But beyond that, it’s because we implemented a campaign designed to communicate to people in Faribault and throughout the Twin Cities area that the facility would be a long-term asset to the community and an environmentally responsible good neighbor.

Not just a plant but a park

The first step in developing the project was our analysis in 2001 and 2002 that clearly showed additional power was required in south-central Minnesota, especially during peak periods.

Site selection was next. We ticked off items on the standard list: access to the grid, access to a fuel source, access to water supplies, reasonable land costs, appropriate zoning, and a welcoming community. But we knew that a “welcoming community” could not be taken for granted. Even communities hungry for economic development can look askance at a power generation facility.

The City of Faribault calls itself “a dynamic, growing city” and is situated at the confluence of the Cannon and Straight Rivers in southern Minnesota. It was an obvious choice for a combined-cycle plant because a natural gas pipeline and a 115-kV Xcel Energy transmission line are located near the boundary of a healthy, expanding industrial park. (See sidebar for the plant specs.)

We knew that a community would welcome us only if we had a better message than, “We’re here to build a power plant in your town.” Avant Energy (formerly Dahlen, Berg & Co.) brought to the board of the Minnesota Municipal Power Agency (MMPA) the concept of creating the plant as a community asset. The Avant concept includes seven rules for integrating a facility into the community in a positive manner:

- Look beyond power generation. The overarching philosophy behind the project needs to answer the question, “What’s in it for the community?” The answers must deal with the obvious, such as providing power and jobs, but they must also address things the community cares about: aesthetics, environmental footprint, economic benefits, and how the plant will support the future of the community.

- Communicate clearly. Configure the project to make it a true asset to the community and tell the story in an honest, straightforward, and effective manner.

- Treat the community as a partner and neighbor. Listen to what citizens are saying.

- Recognize that choice of language is important. Naming the facility was a key consideration. Avant suggested Faribault Energy Park because “energy park” is symbolic of the plant’s well-maintained and park-like appearance and its accessibility to the public for walking, relaxing, bird-watching, and even fishing.

- Make the plant attractive. A master landscaping plan included attractive plantings surrounding plant buildings, plus landscaped areas surrounding holding ponds that featured walking paths and educational displays.

- Design it to be green. Minnesota’s citizens are highly sensitive to environmental issues, so the plant had to be designed as “green” as technologically possible. That included minimizing emissions, handling water wisely, and building in the capability to burn renewable fuel sources, such as vegetable oils (Figure 2). The plant needed to be designed in ways that would allow a positive environmental story to be told.

- Communicate with the community early and often. We offered educational opportunities for the community and designed the facility to enable school and other community groups to tour the facility, learn about energy generation, and enjoy the property. A Web site, www.FaribaultEnergyPark.com, was developed to provide project information and a link through which citizens could ask questions.

2. Multi-fueled gas turbine. A GE Frame 7FA combustion turbine generator being installed in Faribault Energy Park. The plant will also burn recycled vegetable oil, soy oil, and camelina oil. Courtesy: Avant Energy

Avant’s proposal resonated with the MMPA board, which comprises city officials and utility managers from 11 communities in south-central Minnesota—people who could identify their own cities with Faribault.

Openness from day one

A facility of this nature must be well-designed, with the community in mind, in order to be accepted by a host city. A key element of getting the plant built on time and on budget was anticipating community concerns and addressing them in advance.

Those of us in the power generation business aren’t necessarily born to be erudite spokespersons for a project. We’re practical people—focusing on technology, engineering, and the bottom line. But when we’re bringing a high-impact project into a community, we need to learn to be communicators as well. Early in the process—after identifying Faribault as the optimum location for the facility—we decided to seek the expertise of communications professionals. They helped us take several steps:

- We created a communications plan so that we could make an orderly, logical entry into the community. Communications were to always be honest, forthright, and transparent.

- We translated our engineering-speak into well-written, convincing messages to help us tell our story to the community.

- We sought out and identified likely advocates and allies for the plant and we then met these people individually and in small groups.

- We met very early in the process with editors and reporters from the city’s daily newspaper and clearly laid out our plans for the project. We talked about the community benefits and favorable environmental profile of the plant. We also explained the need for more power generation in the region.

- We anticipated possible objections from the community and environmental activists and developed articulate and well-thought-out responses.

Push the envelope

This up-front work wasn’t always easy. It’s not necessarily natural for those of us who are engineers and business people to put ourselves in front of members of the community, risking criticism for what we know to be a smart, responsible plan of action. But it was worth it.

Our open communication with the community was also part of our regulatory approval strategy. Demonstrating a quantifiable need and presenting a responsive and responsible plan for addressing it made gaining regulatory approval a relatively smooth process.

Above all, we became comfortable with articulating our vision: that we could build much more than a power plant. We were building an energy park that would be a long-term asset for the people of the community as well as a source of needed power. And, in the bargain, we could produce power that is efficient and affordable in an environmentally friendly manner.

Telling the environmental advantages of combined-cycle technology was an important part of our Faribault Energy Park message. The environmental story became a compelling one, consisting of: combined-cycle efficiency, low emissions, renewable fuel capability, quiet operation, efficient water management, and an appealing wetlands area accessible to the public.

When you are telling the story of your new plant to the public, it’s important to catalog all the environmental advantages—and perhaps create some new ones, such as environmental education—to be able to assemble a credible, compelling environmental story.

Constructing the plant

Avant Energy was also the construction manager, which helped us maintain consistency from the site selection and design processes. We knew that the good relationships built with the Faribault community during the preconstruction stage could be lost or damaged if we didn’t live up to our word to be a good neighbor during construction. Several actions helped us preserve a positive relationship with the community:

- We hired a veteran construction project manager to be the on-site trail boss of this project.

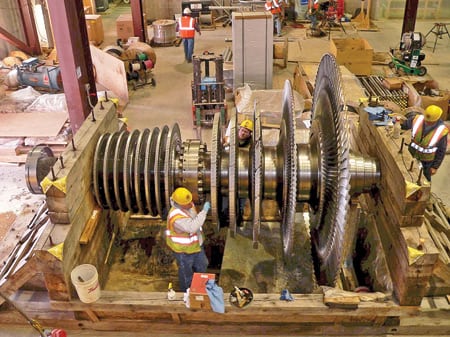

- We went to the Minnesota construction trade unions and let them know we were committed to utilizing the quality and reliability provided by the local trades. The result was a positive working relationship among all the trades throughout all phases of construction. The trades exhibited a remarkable degree of collaboration and contributed greatly to the project meeting its objectives (Figure 3).

- We maintained a flow of communication with the community. We offered to speak at community functions, we joined and participated in Chamber of Commerce meetings, and we invited city and legislative leaders to tour the site. We were open to the media and let them know of important construction milestones. We continued to talk about the economic and environmental attributes of the project. And we listened.

- We ran a clean, safe site. Sloppiness was not tolerated. If not for a minor injury a week before completion, we would have had no lost-time accidents. And remember that construction was undertaken in two phases from 2003 through 2007.

- We made it clear to our on-site team that they were ambassadors for all of Faribault Energy Park, its designers, and developers. As such, they were responsible for maintaining positive relationships in the community.

- We bought locally whenever possible, generating as much economic activity in the community as we could.

- When questions about noise from the plant were raised in 2005 after the initial phase was up and running, we placed decibel meters in several homes surrounding the property and reported on the results.

In short, we went about the business of keeping our promises.

3. Construction team. Workers and tradespeople who built Faribault Energy Park gathered with their families for a group picture at the grand opening. Courtesy: Avant Energy

Celebrating success

The grand opening celebration was something to behold. Based on the food tickets distributed, we estimate that approximately 5,000 people entered Faribault Energy Park’s gates on a beautiful October afternoon last fall (Figure 4). The Faribault Daily News reported the next day that “The only hitch in Saturday’s grand opening of the Faribault Energy Park was that the fish weren’t biting. But countless Faribault residents took the bait Saturday, turning up north of town to check out the environmentally friendly power plant.” The Minneapolis StarTribune also reported that “In addition to power generation, the 35-acre park will serve as an educational facility about environmentally friendly power generation. Visitors can view the control room, steam turbine operations, oil storage and water collection systems from internal and external observation decks.”

4. Grand-opening crowd. Thousands of local residents attended the grand opening of Faribault Energy Park in October 2007. Courtesy: Avant Energy

Faribault Mayor Charles Ackman summed up the feelings of the community in his grand opening ceremony remarks by noting, “Faribault Energy Park is a welcome addition to our community. It is providing good jobs along with amenities you’d never imagine from a power facility, including tours, public use of their park-like wetlands area [Figure 5], and the educational displays.”

5. Local fishing hole. Youngsters drop a line into one of several ponds on the Faribault Energy Park property. The ponds are accessible to the community and are stocked with bass and bluegills. Courtesy: Avant Energy

Crossing the finish line

We know that maintaining a positive reputation in the community is a daily task. A key manager at the site, Mark Tresidder, has responsibility to sustain communications with the community. He acts as the human connection to the facility, schedules tours, and is an active participant in community affairs.

Soon, we will report to the community on our experimental burns of renewable, or biomass, energy sources such as recycled vegetable oil, soy oil, and camelina oil. And as the ground thaws, educational displays demonstrating alternative energy sources including hydro, solar, and wind energy will emerge in the facility’s 20 acres of wetlands.

—Derick Dahlen (derick.dahlen@avantenergy.com) is president of Avant Energy in Minneapolis, which designed and managed construction of Faribault Energy Park and today manages operations. Dave Pokorney (dpokorney@chaskamn.com) is chairman of the Minnesota Municipal Power Agency and the owner/developer of Faribault Energy Park. Pokorney is also city administrator for the city of Chaska, Minn.