South Africa’s state-owned utility Eskom was forced to slash 2,000 MW on a rotational basis nationwide on Oct. 16 and Oct. 17. The newest round of power cuts—the first in nearly seven months—highlight the state-owned utility’s scramble to avert financial disaster stemming in part from the fast-tracked construction of two 4.8-GW coal-fired power plants: Medupi and Kusile.

The 1923-established vertically integrated utility that produces more than 90% of the country’s electricity operates 30 power stations with a nominal capacity of 44.2 GW, the bulk of which, 36.5 GW, is from coal-fired power plants. It also sources 1.9 GW from the 1984-built Koeberg nuclear plant near Cape Town; 2.4-GW from natural gas–fired plants; 600-MW from hydro; and 2.7-GW from pumped storage facilities. Its network, which encapsulates nearly 388,000 kilometers (km) of high-, medium-, and low-voltage lines and underground cables, is a crucial supplier to both South Africa and the Southern Africa Power Pool, which includes power-hungry neighbors Botswana, eSwatini, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. And, as experts note, it forms the backbone of the region’s power market—which is the largest in Africa and the 18th largest in the world in terms of domestic demand—and it is a structurally critical aspect of South Africa’s economy.

That’s one reason during his state of nation address in February 2019, President Cyril Ramaphosa claimed Eskom—which employed 46,664 employees at the end of 2018—was “too big and important” for the government to “let it fail.”

But Eskom has now become a “debt-stricken headache for Pretoria,” as CNBC noted in October. Though the company embarked on an ambitious $13.2 billion generation expansion plan in 2007 in response to a series of unprecedented power shortages, this year, the country suffered some of it most serious power cuts.

[Read more about why Eskom embarked on its ambitious capacity expansion in POWER‘s award-winning analysis from its November 2008 issue: “Whistling in the dark: Inside South Africa’s power crisis.”]

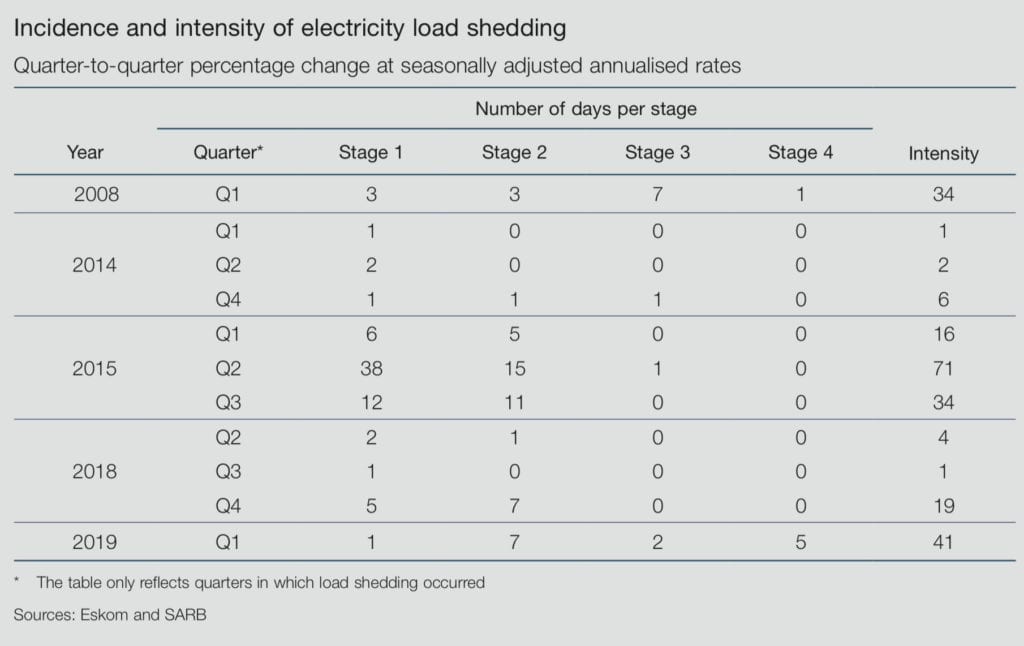

The South African Reserve Bank, which actually assessed the intensity of load shedding’s effect on the economy by quarter, noted in September that the first quarter of 2019 was especially detrimental to economic growth. South Africa suffered load shedding in 2008, 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2019. The year 2015 had the most incidents—52 days in total; that compares to 16 days in 2018, and 15 days in the first quarter of 2019 alone.

But in 2019, for the first time since a single incident in 2008, Eskom recorded five Stage 4 incidents. Stage 4 incidents indicate up to 4 GW of load was shed nationally on a rotational basis. “Loadshedding is a highly controlled process, implemented to protect the system and to prevent a total collapse of the system or a national blackout,” Eskom explained in a press release as it implemented one such incident on March 18. The utility urged customers there was “no cause for alarm.” It added: “During Stage 4 loadshedding, approximately 80% of the country’s demand is still being met.” As of October, supplies remained tight, but Eskom had avoided load shedding since March, a feat it pegged to successful implementation if a “nine-point generation recovery plan.”

However, the events this year have spooked potential investors and added a burden to South Africa’s economic growth—which in 2019 entered its 70th month of a downward cycle, the longest since 1945, according to the Reserve Bank. As of early October, both S&P Global Ratings and Fitch have already deemed the country’s debt at sub investment grade, labelling it “junk.” The World Bank in October also cut the country’s growth forecast through 2021, citing lingering policy uncertainty. Dominating that uncertainty is Eskom’s failure to boost output, analysts said, along with concerns about chronic liquidity problems, and reported mismanagement and malfeasance.

Eskom has been embroiled in serious scandals involving irregularly awarded coal contracts for coal—including for poor quality coal and coal not received, and unlawful procurement of services for global consultancy firm McKinsey and its subcontracted Trillian Management Consultancy, a company linked to the Gupta family. Authorities are also investigating allegations of maladministration and corruption at various power plants, including of Medupi and Kusile, through the new build program, which has so far delivered 10.8 GW and nearly 8,000 km of new lines to the country’s grid.

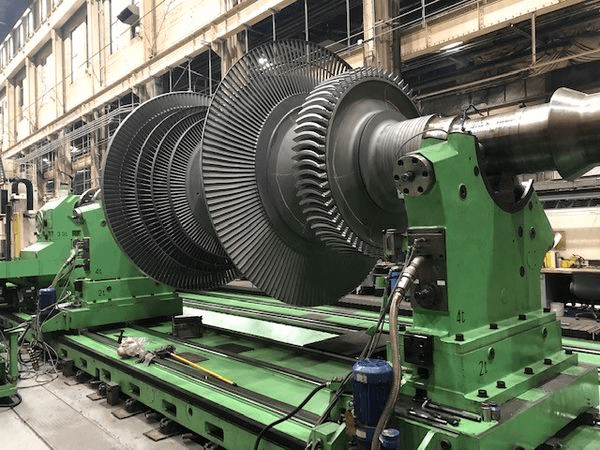

For now, at least, all six 800-MW units at Medupi and two of another six at Kusile have come online (Figure 2). Both plants, which were approved in 2007, were expected to be finished by 2015. However, Eskom notes that the operational Medupi and Kusile units—as well as the four-unit 1.3-GW Ingula pumped storage scheme, a project that took 12 years to complete—are plagued by “major design and construction defects,” and “operational and maintenance inefficiencies,” which are direly affecting plant performance.

Compounding delays stemming from a lack of skills, and inadequate planning and front-end engineering development for the fast-tracked projects, at seven units across Medupi and Kusile, Eskom is working on a redesign of the pulse jet fabric filter plant; modifications of coal mills; repairs of dust handing plants, ash silos, and conditioning plants; and solutions to remedy defects in the control and instrumentation systems. At all four Ingula units, the major defect is related to “dual load rejection.” Relief—in the form of surplus capacity—is out of reach for at least a few more years. While the last Medupi unit was synchronized to the grid in August 2019, Eskom pushed out the plant’s completion date out to 2021, and Kusile’s, to 2023. It is unclear when Ingula will be fully back online.

Uncertainty about project timing is so debilitating that Eskom has even considered the feasibility of continuing or stopping construction at Medupi and Kusile. But it concluded it would cost more—140 billion rand ($9.5 billion)—to scrap uncompleted units if all claims and penalties and charges to impair the assets and pay back lenders were accounted for. In April, it noted, Medupi had spent about 89% of its 145 billion rand ($9.8 billion) budget, and construction was 95% complete. Kusile had spent 87% of its 161 billion rand ($10.9 billion) budget, and construction was 87% complete. The “major plant defects” would cost about 7.2 billion rand ($487 million)—and some of that “will be recoverable from liable contractors.” Until then, the company will just be forced to rely extensively on its costly, diesel-fired open-cycle gas (OCGT) turbines and lean on independently produced power.

Meanwhile, Eskom will also need to grapple with several other significant issues that bar it from bridging South Africa’s critical power shortfall. One is the “rapid and unexpected deterioration in generation plant performance,” owing to “record levels of unplanned maintenance,” at its aging coal plants. In April 2019, as the company intensified load shedding, at least 760 MW of capacity was out of service for “major repairs,” and another 1.3 GW, including 10 units at Hendrina, Grootvlei, and Komati Power Stations, weremothballed because “they have become uneconomical to run.” In September, Eskom said an average of 5.5 GW of planned maintenance will be performed to keep unplanned plant breakdowns below 9.5 GW to safeguard against summer load shedding.

But over the next five years, it notes, another 4.8 GW is due for shutdown over the next five years as they reach the end of their useful lives—which makes fixing existing plants and completing Medupi and Kusile more critical. Priorities in the ambitious “nine-point generation recovery plan,” for example, call for fixing new plants; fixing full load losses and trips; fixing units on long-term forced outages; fixing partial losses and boiler tube leaks; fixing outage durations and slips; fixing human capital; preparing for increased OCGT usage; reducing emissions; and fixing coal stock piles.

Finally, Eskom’s most critical—and seemingly unsurmountable—hurdle is tackle “a significant decline in liquidity, due in part to escalating municipal arrear debt and rising debt service costs, exacerbated by lower than required price increases awarded by [the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA), the federal agency, that regulates the power sector and determines Eskom’s revenue requirements].” Owing to NERSA’s inadequate tariff awards, the utility says that it is hobbled by a stunning debt burden of 450 billion rand ($30 billion). NERSA’s latest tariff decision to increase tariffs by between 5.2% and 9.4% over the next three years by NERSA in March, it said, will leave Eskom with a projected revenue shortfall of around 100 billion rand ($6.7 billion). But NERSA explained that it arrived at its decision having offset a bailout granted to Eskom this February by the Minister of Finance of 23 billion rand ($1.5 billion) for the next three years. In August, the Department of Public Enterprises noted that the Finance Ministry had tabled a “special appropriation bill) that would inject another 59 billion rand into Eskom, effectively bringing total bailout funds to 128 billion rand ($8 billion) over a three year period.

However, the utility balks at being forced to rely on government bailouts to survive because it opens it up to “ongoing political intervention,” it said in its April-released 2018 integrated report. “To enhance our autonomy, we need to turn around our operational and financial performance and rebuild Eskom as a sustainable organization, albeit with a strong developmental mandate.” That’s one reason that the utility on Oct. 11 took the desperate step of challenging NERSA’s latest tariff decision in court. Company officials argued it needed this “urgent interim relief” because it was “necessary to avoid financial disaster.”

South Africa’s government, meanwhile, granted the bailout under the condition that the company establish a “restructuring office” that would deal with debt and “interrogate various proposals to resolve Eskom financial challenges.” In August, the government said one avenue it is pushing is to split the company into three entities, starting with a creation of a transmission entity—a recommendation that is in line with government ambitions outlined as far back as 1998. Privatization of Eskom may not be on the table, however: President Ramaphosa told lawmakers in October that Eskom’s plants are “Crown Jewels,” and that “South Africa is not inherently in the business of selling power stations.” For now, more light on how the country will proceed to diminish Eskom’s massive debt may be shed in a government “special paper,” which the government said in August will clearly outline a roadmap for Eskom’s “long-term sustainability.”

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine)