Steve Elonka began chronicling the exploits of Marmaduke Surfaceblow—a six-foot-four marine engineer with a steel brush mustache and a foghorn voice—in POWER in 1948, when Marmy raised the wooden mast of the SS Asia Sun with the help of two cobras and a case of Sandpaper Gin. Marmy’s simple solutions to seemingly intractable plant problems remain timeless. This Classic Marmaduke story, published more than 50 years ago, reminds us that even the most modern steam plant is only as good as its operators.

“Something’s haywire,” observed young Marmaduke Surfaceblow when he reached the large cottonwood tree only a block from the village power plant. The young man automatically stopped to listen and look down the dusty road at the small, red brick plant near the river. The high steel stack belched a plume of thick grey smoke, which spread over the low evening sun’s embarrassed face. As the young man listened, he knew from the sound of the exhaust that the large compound engine was running. “Wonder why?” he crackled in his deep voice, clamping an unlighted cheroot between strong white teeth. Then, taking giant steps, he hurried downhill to the plant.

Milldew, Missouri, on that long-ago day shortly after World War I, had a scant 200 inhabitants. But the little Mississippi River hamlet would one day become famous for having been the hometown of the senior member of Surfaceblow & Associate, internationally respected New York consulting engineers. At age 15, Marmaduke was already an overgrown, rawboned country lad, 6 feet in height. And he had been rattling over the red-clay Missouri country roads in a model-T Ford ever since his legs were long enough to reach the floorboard pedals.

Fact is, since age 10, Marmy, as he was fondly called by the natives, had been helping Thaddeus McSpadden with his blacksmithing, overhauling farm machinery, Stanley steamers, and the “gas buggies” of the period. Then, during the hectic autumn harvesting seasons, the youthful embryo mechanical genius had fired and operated steam threshing engines, some fitted with straw-burning boilers, as well as any grownup.

Marmaduke had spent his 14th birthday, stripped to the waist, shoveling coal into the hungry boilers of the Mississippi River side-wheeler, the Great Republic. By the time the river queen returned to St. Louis from New Orleans, Marmy could handle a slice bar and keep steam on the line along with the burliest river firemen.

“If that young’un Marmy can’t fix it, better bury it,” was heard frequently around the Milldew countryside. And that included repairing everything from grandfather clocks to internal-combustion engines.

Now, with the war having claimed one of his shift operators, chief engineer Diogenes Bluer, an old friend of Thaddeus McSpadden, had put the youngster on as an operator at the “electric light” plant. Marmaduke had the night shift, starting at 6 p.m. It was a 12-hour “day,” and his pay was $100 a month. Not bad for the times, the job and the hamlet, no siree—not to mention for a youngster of only 15.

The small plant had four horizontal-return-tube (HRT) boilers, rated at 150 boiler hp, on that day’s basis of 10 sq. ft. of heating surface equaling 1 boiler hp. Although some backward areas still use this antiquated method, we rate boilers today on pounds of steam produced per hour.

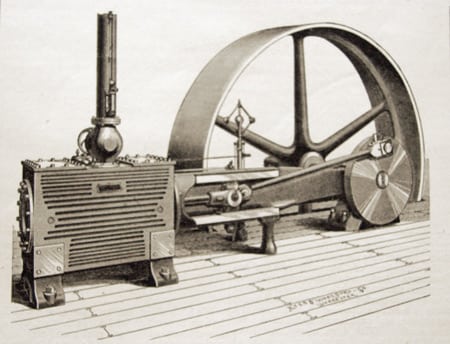

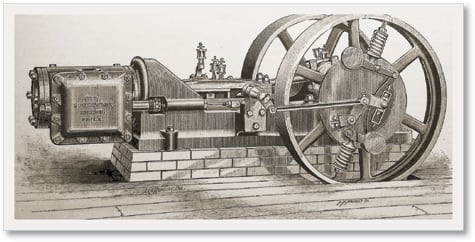

Two horizontal Buckeye steam engines drove shaft-mounted alternators with belted exciters. The small single-cylinder engine, dubbed “Little Buck,” was rated at 75 kW; the larger, cross-compound “Big Buck” at 150 kW.

Sure, today those old timers sound insignificant in capacity. But to the youthful country lad, the large unit, especially, with its heavy flywheel spinning and its crosshead reciprocating steadily to and fro, seemed impressive enough. Each engine had one piston-type valve, and the compound’s low-pressure side had a slide valve.

Usual practice was to run the small unit from midnight to around 7 a.m., the time when the load started climbing. Peak load was from 140 to 150 kW—except on Saturday nights, when it shot up to 175 or even 180 kW, and the compound needed help from the smaller engine.

On Saturday, farmers drove to town by buckboard, or with their Webber & Dame green farm wagons loaded with produce and children, or in their Tin Lizzies. The younger people would congregate around the ice-cream parlor next door to Enoch Fidley’s Feed & Grain Exchange. Smedley’s Tonsorial Emporium and the grand Pool Parlor next door would buzz with activity. And the new Lyceum Movie Palace, boasting 100 seats and recently completed in what had been Jastrow’s Livery Stable, would have standing room only, especially if Harry Carey starred in a cowboy picture and Charlie Chaplin added icing to the evening’s cake.

On Saturday evenings, merchants along River Road had their stores a blaze with electric lights, displaying merchandise stacked on the sidewalk beneath the wide veranda that extended along the storefronts from one end of the block to the other.

Yessir, while the biggest excitement on weekdays might be a dogfight or two on dusty River Road in front of Schwartz’s Butcher Shop, on Saturday the town always came alive. And this WAS Saturday.

Marmaduke opened the engine-room door and apprehensively stepped inside. He was enveloped by the warm, sweet aroma of steam in contact with cylinder oil. And the big compound was throbbing steadily away as it reciprocated majestically, hissing light feathers of steam from stuffing boxes at the end of each stroke. The spokes of the massive flywheel were a blur, and its vertical fly-ball governor spun in merry-go-round fashion. Beyond Big Buck, Marmy saw Cyrus Clooney, the day operator, through the blurred flywheel spokes, working away at something over Little Buck.

Stopping for a second, Marmaduke watched Clooney. What was he doing—fishing a piece of broken piston ring out of the smaller engine’s steam passage? The young man knew instantly what had happened. Yes, Little Buck had evidently taken a drink of water which knocked out her cylinder head, bent her piston rod, and broke the rings on her piston valve.

“Looks like a tornado’s been here. What a mess,” rumbled Marmaduke, lighting the cheroot and taking a drag on it. “Where’s Diogenes?”

“Idunno—reckon he’s gone home to supper,” came the unconcerned reply from Cyrus as he continued his fishing expedition. “And that’s where I’m heading, soon as I snare this last dagnabbed piece of ring out of this here port.”

Now, chief engineer Diogenes Bluer was of the old school. Like operating engineers of the day, he had got his “schooling” by starting out as a “boomer engineer,” firing HRT boilers and operating steam engines at whistle stops throughout the country. After satisfying his wanderlust and acquiring a first-hand knowledge of boilers and engines, from simple “side-winders” to the stately Corliss, he had returned to settle down back in his hometown.

Diogenes was a big, burly man of about 250 pounds, with a close-cropped grey mustache and a bald head, which was always covered by a ten-gallon hat, his trademark. Although on the quiet side while on the job, Marmaduke soon learned that the chief had all the right answers when the chips were down. Chief Diogenes, as he was respectfully known throughout the Ozarks, and young Marmaduke had a great deal of respect for each other.

“She’s all yours,” exclaimed Cyrus, dropping the last piece of piston ring on the workbench. He squirted lube oil on his grimy hands, rubbed them together to work off the dirt, then vigorously wiped them with waste. “I’m making tracks, taking Rosie Gerber to the barn dance out at Pevely’s new electrified farm,” he added as he signed the log book. Then, reaching the door, “I’ll be thinking of you when Bib Buck starts calling for help. And if the lights go out, me and Rosie won’t mind—ha, ha.” He was gone.

Marmaduke knew it was HIS time to start worrying. How was he going to get by with the smaller engine torn apart and the peak load sure to follow in another two hours?

Perhaps chief Diogenes thought leaving the young man by himself in a tight situation would be good for him. Or maybe he wanted to see exactly how Marmy would act in an emergency. Who knows? At any rate, the chief didn’t show up for two very, VERY long hours. By then, the load had been inching up steadily, and the youthful operator was extremely concerned. It was his first job as a shift operator in a steam power-generating station; he had started only three weeks ago! And this was the first time he had faced the peak load all by himself, with Little Buck’s anatomy scattered over the floor. Worst of all, if the breaker tripped, River Road would be thrown into darkness. And the entire Ozark countryside would remember only that the blackout occurred on Marmaduke’s shift. Now THAT would be something to carry to his grave.

Just as the embryo engineer, with eyes glued anxiously to the wooden instrument panel, was wondering WHAT he could do to prevent the breaker from tripping—lash it down? No, never—he felt a cool breeze flow in as the back door of the engine room opened. It was Diogenes himself. The big man never looked so big as he did to the young man at that moment.

“Gosh, Diogenes, am I glad to see YOU,” blurted the young man. “The load’s nearing one-fifty, and Big Buck’s about to start slowing down. What should I do?”

Diogenes didn’t answer, giving the impression he had had a very leisurely and satisfying dinner and now wanted only to enjoy a smoke. He walked slowly to the instrument board and glanced at the steam gage, then at the frequency indicator. The meter registered slightly below 60 cycles. Removing the corncob pipe from his mouth, he tamped down the tobacco with his little finger, struck a wooden match with one hand by scratching it with his thumbnail, lit the pipe and drawled. “Just you keep your shirt on, young feller.”

Then, glancing at the steam gage, “Go tell Alex to keep the water low in the glasses—maybe a half-inch above the nut—and his boiler pressure right up on the pop valves.”

The perplexed young operator looked on in disbelief as the chief lumbered over to his swivel chair, pulled it across the floor to the side of the compound painted base, pulled the brim of his hat over his eyes, and leaned back in his chair as if going to sleep.

“He’s blown all his gaskets,” thought the concerned young operator. “Peak load coming up, no reserve power, and he’s hitting the hay.” But now that the chief had returned, at least the problem was on HIS shoulders. Marmaduke walked into the fireroom.

The fireman has pushed a wheelbarrow of coal in from the outside coal pile, and was dumping it in front of a boiler. “Alex, chief Diogenes wants you to keep the water low, just above the bottom nut. No time for Big Buck to get a shot of water. And he wants that steam right up on the pops,” relayed Marmaduke.

The fireman glanced up at the steam gage, then quickly at the water level in the gage glasses. Hoisting one foot up on the empty wheelbarrow, he removed the sweat towel from his neck, and wiped the perspiration and coal dust from his neck, face and forehead. “Well, she’s right up there now, Marmy, old chum. If she goes any higher she’ll pop, that’s for sure.” With that, he opened a furnace door. The hot glare from the flames flooded Alex in a blaze of red light, magnifying into a giant shadow on the boiler front opposite. Alex got busy with the slice bar, breaking up a large clinker on the coal bed.

Marmaduke walked back into the engine room. Yep, the chief was still reclining in his chair, hadn’t changed his position. So the young man dismissed the immediate problem from his mind, and set to work routinely checking the oil cups on the compound. He felt the main bearings with the back of his hand, as Diogenes had taught him, then reached for the long-spouted oil can and started filling the cups. But all that time, he kept glancing at the chief.

Suddenly, Marmaduke realized that chief Diogenes wasn’t snoozing after all! He was quietly and comfortably observing the motion of the valve gear.

The engine had an inside traveling cut-off, and, as the load built up, the travel increased. Sure, that’s what the old fox was up to—observing the valve gear from where he sat, he could see when the valve’s travel was nearing its full-out position.

“Marmy, come here,” called the chief, as soon as he decided that the valve travel had reached the full-out point. The young man hurried to the chief’s chair. And it was at that point that Marmaduke Surfaceblow got his first important lesson in compound steam engine operation. Bluer pointed to the one-inch line tapped into the main steam line just above the throttle and low-pressure cylinder chests. A valved branch of the one-inch line extended down into the sewer.

Young Marmaduke knew the line was used to drain the main steam line in to the sewer before warming up the engine. He also knew it served to “goose” the engine on the low-pressure side when, on shutdown, the h-p piston came to rest at dead-center.

“You just eyeball that steam on the receiver, Marmy, and see what happens,” instructed the chief. Marmaduke glued his alert eyes onto the gage. It registered about 12 psi, which he knew was normal for the load.

The chief started cracking the valve on the one-inch line to the receiver. And Marmaduke observed the receiver pressure start building up, ever so gradually. As soon as it reached 15 psi, Big Buck perked up considerably, cranking away in earnest, and it came right up on the governor. The young man also observed that the frequency indicator was again riding smoothly at 60 cycles.

Chief Diogenes didn’t have to explain what he was doing, nor why. Young Marmaduke had the picture instantly, mentally kicking himself for not having thought of it before. All he had to do was observe that the one-inch line connected the main steam from the boiler to the steam chest of the l-p cylinder’s valve, thus bypassing the h-p cylinder and bleeding boiler pressure steam directly into the l-p cylinder.

Young Marmaduke had the picture instantly, mentally kicking himself for not having thought of it before. Source: POWER

From that day he never failed to study thoroughly every piece of equipment he operated, so he could take care of every mechanical hookup to keep his plant running.

In years to come, he would bring in several triple-expansion engine-powered ships on only one cylinder, and several others on two. Not only that, but right then and there young Marmy made up his mind to make a career of power-plant operation—that’s how impressed he was with the way chief Diogenes met the peak load with his ingenious one-inch piping.

Two weeks later, the needed parts for Little Buck arrived from the factory up-river in Dubuque, Iowa. Marmaduke and Cyrus spent their watches assembling Little Buck under the watchful eyes of Diogenes Bluer, with a few hours of help from Thaddeus McSpadden, the blacksmith. By the following weekend, the single-cylinder Little Buck was ready to assist Big Buck with the heavy Saturday night load.

Since that long-ago day back in Milldew, considerable bilgewater has been pumped over the sides of many ships. And Marmaduke has helped grind out kilowatts galore, not to mention solving numerous perplexing energy-systems problems in various corners of the globe. But chief Diogenes’ actions that day taught the youngster one important lesson he has made excellent use of many times since: Energy systems equipment, regardless of how sophisticated, is only as reliable as the operator in charge.

[Note: If you enjoyed this tale of Marmaduke Surfaceblow’s adventures, visit the POWER Store to purchase a compilation of stories that originally were published in POWER—Marmaduke Surfaceblow’s Salty Technical Romances. ]