The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) on June 15 indefinitely suspended spot markets in all regions of its National Electricity Market (NEM), citing critical power generation supply shortfalls that it said made it “impossible to continue” operations under national electricity rules.

AEMO—the independent system operator (ISO) that operates the competitive market serving New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria, and Tasmania—said its spot market suspension stems from unprecedented market volatility that has been exacerbated by several factors.

Scrambling to meet supply shortfalls forecast in Queensland and New South Wales for June 14, AEMO was forced to activate 5 GW of generation that hadn’t bid into the market “through direct interventions,” said AEMO CEO Daniel Westerman. While the grid operator managed to avoid load shedding, those interventions, which follow a series of similar near-misses, showed “it was no longer possible to reliably operate the spot market or the power system this way,” Westerman said.

“In the current situation suspending the market is the best way to ensure a reliable supply of electricity for Australian homes and businesses. The situation in recent days has posed challenges to the entire energy industry, and suspending the market would simplify operations during the significant outages across the energy supply chain,” he said.

The market suspension is temporary—but no end is in sight. AEMO said the suspension “will be reviewed daily” for each NEM region. “When conditions change, and AEMO is able to resume operating the market under normal rules, it will do so as soon as practical.”

And while the spot market suspension poses a radical step, some Australian power market participants view it as an inevitable outcome, suggesting it is reflective of the extreme market conditions. “A suspended market is better than where we were before: where some generators were in the market while others were being directed,” said Sarah McNamara, CEO of the Australian Energy Council (AEC), a trade group that represents 20 major power and gas companies that participate in the competitive wholesale markets.

At Issue: Generator Withdrawals Are Intensifying an Acute Supply Shortage

Westerman said that “price caps, coupled with significant unplanned outages and supply chain challenges for coal and gas, were leading to generators removing capacity from the market.”

AEMO’s most recent turmoil ensued on June 12, when electricity spot prices in Queensland reached a cumulative high price threshold of A$1,359,100 (accumulated over seven days) on June 12, automatically triggering an administered price cap of A$300/MWh (US$ 208.60/MWh) in accordance with the National Electricity Rules (NERs).

NERs set a maximum spot price (also known as a maximum price cap). An administered price period occurs when the rolling seven-day average of wholesale spot prices breaches the cumulative prices threshold (CPT), which is now based on five-minute prices and is set at A$1,359,100—the equivalent of the spot price being set at the market price cap of A$15,100/MWh, continuously, for 7.5 hours. In recent days, the seven-day cumulative spot price in several NEM regions has at times veered close to the CPT, Westerman noted.

It is “understandable” that generators are responding to price caps, he said, but nearly 3 GW of coal-fired generation was out of service through unplanned events as of June 15. A large number of generators were also “out of action” for planned maintenance—which is “a typical situation in the shoulder seasons”—but this year, NEM’s reliability outlook has been complicated by an early onset of winter, which has ramped up demand for both power and gas, he said. Adding to that complexity are planned transmission outages and periods of low wind and solar output.

Westerman said that “with the high number of units that were out of service and the early onset of winter, [AEMO’s] reliance on [directing generator participation] has made it impossible to continue normal operation.”

A Radical Step for the 1998-Established Spot Market

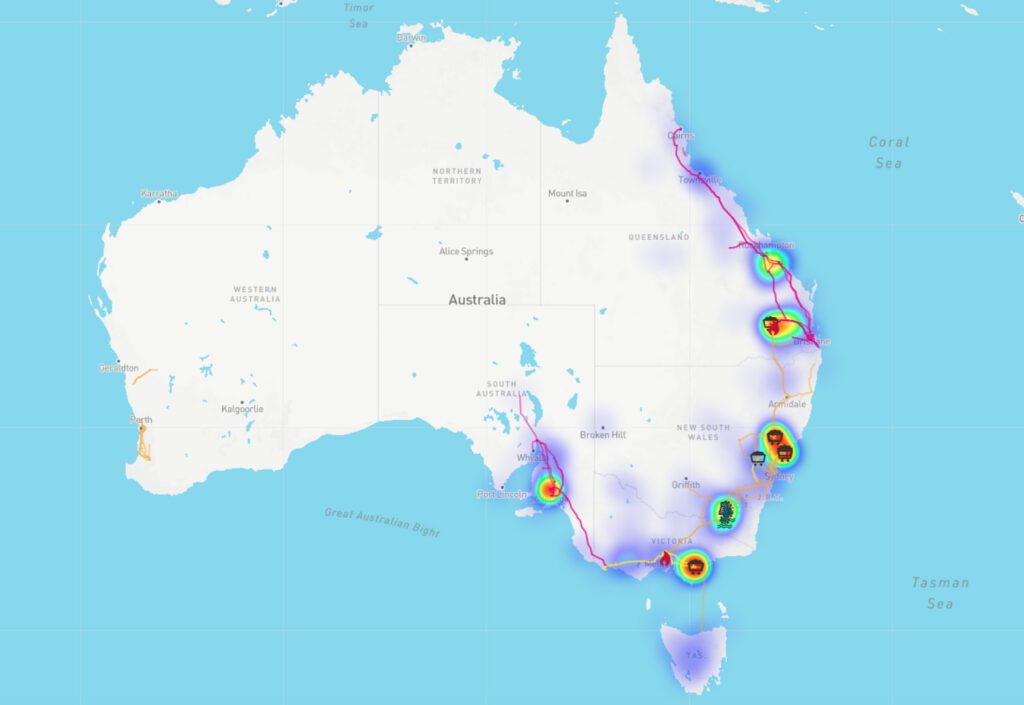

AEMO’s suspension of the spot market marks a dramatic escalation for NEM, one of the world’s longest interconnected power systems. NEM was established in 1998 as a wholesale spot market, and it had a combined generating capacity of 65.2 GW and 504 registered participants, including generators, transmission service providers, distribution service providers, and customers as of December 2021.

NEM spans Australia’s eastern and southeastern coasts—a distance of around 5,000 kilometers—comprising five interconnected states, which also act as price regions: Queensland, New South Wales (including the Australian Capital Territory), South Australia, Victoria, and Tasmania. Western Australia and the Northern Territory are not connected to the NEM, owing mainly to the distance between the networks.

The spot market, AEMO notes, works as a “pool,” where power supply and demand are instantly matched through AEMO’s centrally coordinated dispatch process. NEM relies on generators to bid supply with specific capacity at specified prices for a set time period. AEMO decides which bids will be accepted, though rules require the cheapest generators are put into operation first.

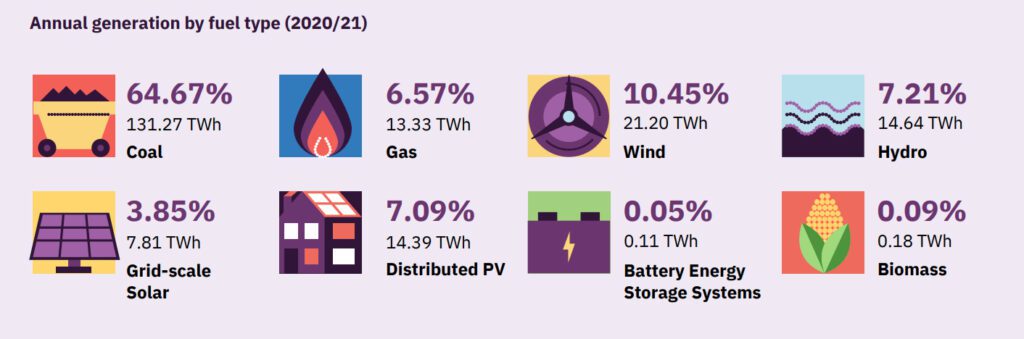

In October 2021, notably, AEMO shifted the 30-minute price determination to five minutes as part of an effort to provide better price signals for investment by faster-response technologies, such as batteries and gas peaking generators. That effort was tailored for more flexibility as Australia’s power mix continues a rapid transformation toward renewables. “At current rates of development, there could be sufficient renewable resources available to meet 100% of underlying consumer demand in certain periods by 2025,” AEMO has said.

Australian Regulators Respond to Market Turmoil

Turmoil in Australia’s power markets owing to its rapidly changing landscape and volatile generator participation has concerned regulators, like the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), an economic regulator for the wholesale energy markets.

In a June 14 letter to NEM market participants, AER notably warned generators that are withdrawing available capacity from the market—especially if that behavior is to avoid the administered pricing cap—to heed market rule obligations. “Market participants must not by any act or omission, whether intentionally or recklessly, cause or significantly contribute to the circumstances causing a direction to be issued, without reasonable cause,” wrote AER Chair Clare Savage.

National gas and power market rule-maker Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC), meanwhile, has set out to improve the quality and transparency of generator outages. The agency published a draft rule on May 26 as part of its medium-term projected assessment of system adequacy (MT PASA) process “to improve understanding about why particular generators are unavailable and how long they would take to come back online.” The draft rule, however, also requires generators to lodge a “reason” and a “recall time” when submitting their expected availability.

“As older generators approach the end of their technical life, their operators may shift to cyclical operating regimes, opting only to generate for certain periods of the year to maximize their profitability. This is due to large amounts of renewable energy generators entering the market and applying downward pressure on prices, especially at particular times of the day and year,” the AEMC acknowledged. The AEMC said that as more generators move to cyclical operating regimes, the challenge of operating the power system to deliver reliable, secure supply is expected to grow.

The AEMC has also acted quickly in response to recent market volatility in the NEM. On June 15, the regulator rolled out an administered price cap (APC) compensation process that allows scheduled generators, non-scheduled generators, scheduled network service providers, scheduled loads, ancillary service providers, and demand response service providers to bid into the market while providing protection from losses.

Under the process, which the AEMC will run independently (and will apply to eligible generators who supply during the AEMO’s suspension price periods), these parties can claim compensation if they provided energy or other services during an administered price period and incurred a net loss. “That is, their direct and/or opportunity costs exceeded their total revenue from the spot market over an entire ‘eligibility period,’ ” the AEMC specified.

While the CPT is designed “to protect customers from extended high price periods,” the APC compensation process, is “aimed to ensure generators continue to bid into the market and they do not face losses during this period,” the AEMC explained.

Is the NEM Broken? No, Says Power and Gas Trade Group

According to trade group AEC’s McNamara, the NEM’s suspension may ultimately lead to much-needed reform. “Is the NEM broken? The short answer is no,” she noted in a blog post explaining the current energy crisis. “The long answer is recent events have revealed the need for some simple, but important repairs.”

McNamara suggested the crisis has been “a combination punch of shocks: global energy shortage, increased exposure to spot prices, cold, wet weather, and unplanned, prolonged outages.”

The result: A “perfect storm” of disruptions for Australia, which has historically been a substantial net exporter of energy, including coal and natural gas. The country’s net exports equate to over two-thirds of production. Around 90% of black coal energy production was exported in 2020, as was around 74% of domestic natural gas production, the government says.

Oil, gas, and coal sanctions imposed on Russia prompted an “aggressive re-contracting of available energy supply chains,” which “sent global prices for these fossil fuels to record highs,” noted McNamara.

Meanwhile, domestic coal suppliers are underperforming. Some power plants in New South Wales have struggled to secure enough coal owing to flooding incidents earlier this year. Origin Energy, Australia’s second-largest power producer, earlier this month said it faced problems obtaining enough coal for the 2.9-GW Eraring power station in New South Wales, the country’s largest coal-fired plant, from Centennial Coal, its supplier.

“However, the situation has deteriorated significantly in recent weeks, with material under-delivery of coal compared to expectations, and with Centennial Coal notifying Origin of further production constraints at its Mandalong mine,” the company warned in an earnings report on June 1. Origin expects deliveries from the Mandalong mine will be interrupted for the remainder of this year and into the first half of 2023. “Equipment supply chain delays are also expected to impact coal deliveries in FY2023,” it said.

Combined with global price shocks, supply uncertainties have sent spot market prices for black coal in Australia soaring above A$500 per tonne and A$40 per gigajoule (GJ) for natural gas. “These prices are four to five times the long-term average,” McNamara said.

“These high fuel prices have driven up the price of electricity, as generators have had to compete with these international spot prices to buy some of their fuel,” she explained. “Coal generators are more exposed to spot prices now because they have been reducing forward-contracting in anticipation of continued increases in renewable generation. That’s how the transformation was supposed to work.”

The price spike, however, hit Australia at the same time as “a fierce June cold snap, following two months of low wind generation, reduced coal stockpiles, and heavy rains slowing coal mine output,” she said. “Solar output is below average due to the shorter days.” Unscheduled outages in some coal generation units have made the crisis worse. An estimated 25% of the market’s 23 GW of coal-fired capacity is currently out of service. “The disruption to global supply chains is causing delays in getting essential parts to fix these units,” she noted.

The combination of these factors resulted in more than a week of very high wholesale power prices, which triggered the NEM automatic price cap at A$300/MWh. “This price cap mechanism was designed when the NEM was created in 1998 to manage short-term events like summer heat waves,” McNamara said. “Longer-term global energy shortages like now were not anticipated. Sustained higher wholesale prices are the market solving for the combination of problems it faces: high demand, some units unavailable, and the need to ration scarce coal at some power stations.”

The Price Cap: Unworkable Under Current Conditions

A key issue is that the price cap has not been updated in more than 20 years, McNamara noted. “It was originally designed to reflect the maximum price a gas peaker would need to recover its costs. But with gas prices currently at A$40/GJ (which is also an artificial cap, so we know that’s as high as it can go), this ceiling would need to be around A$500/MWh to ensure all generators can cover their costs,” she said.

Coal generators, meanwhile, are rationing their fuel supplies to ensure power plants will have enough coal to meet morning and evening peaks. “So they deliberately bid in higher prices at other times to bid themselves out of the market,” said McNamara. “This lets them save more coal for when it is needed and lets generators with more coal take up the slack. It’s an oddly elegant way the market solves for the third-dimensional problem of coal scarcity.”

The trouble is that when a price cap is introduced, “this coal rationing regime doesn’t work,” McNamara explained. Under current NERs, a generator that has bid into the NEM “must be fully utilized” before AEMO can direct other generators to turn on. “This inadvertently discourages generators with low coal reserves from bidding in at all. Once directed on by AEMO they can work together to manage limited coal stockpiles to optimize output,” she said.

That’s why the “problem here isn’t the generators withdrawing units. The problem is that the automatic price cap is interfering with the market doing its job and complicating the way generators are paid for doing the same thing,” she explained. “This response to the price cap has not increased the risk of outages or impacted on prices paid by consumers. If anything, it has helped reduce reliability risk.”

Ultimately, AEMO will need to either remove the automatic price cap and “let the market solve (as it was doing), or at least increase its value, or agree on conditions that trigger AEMO dispatching all generation, so that it can co-ordinate market dispatch under extreme conditions,” she said.

“We need to do everything we can to resolve this crisis as quickly as possible. Australia’s energy industry will continue to work with governments, agencies, and other stakeholders to achieve this,” McNamara added.

—Sonal Patel is a POWER senior associate editor (@sonalcpatel, @POWERmagazine).