This is indeed an extraordinary time to be in nuclear energy. Case in point: Over the past few months, we have seen an announcement between Microsoft and Constellation Energy to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, a $1.5 billion loan guarantee from the Department of Energy (DOE) to restart another reactor in Michigan, and a new DOE liftoff report on how to build new nuclear facilities.

We are witnessing much more demand from data centers and industrial facilities for the reliable, carbon-free power that nuclear plants produce and unprecedented federal government support. In addition, the U.S. government recognizes that we cannot achieve 2050 net-zero decarbonization goals without including new nuclear builds as a significant part of the mix.

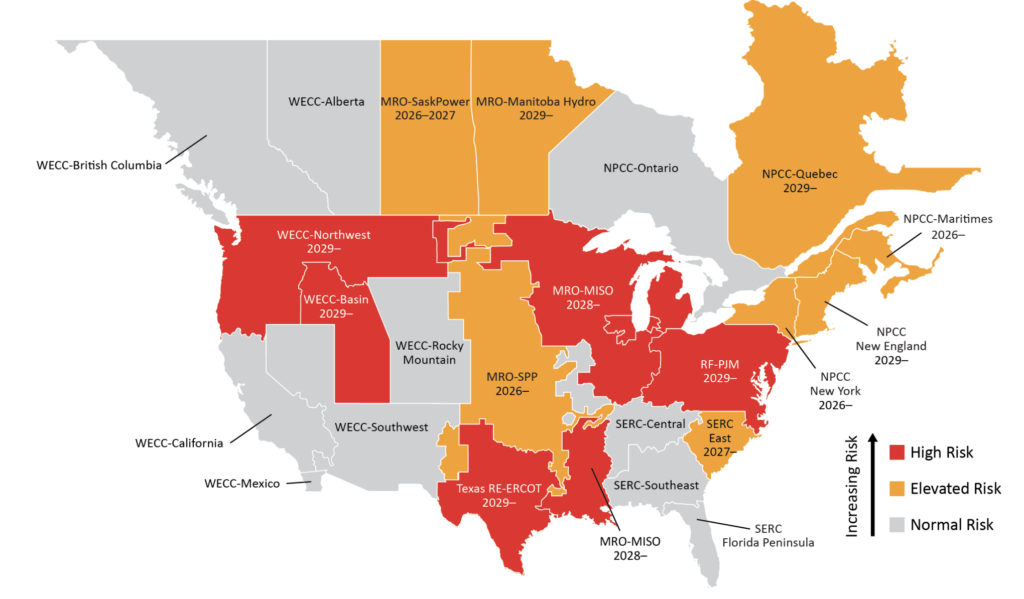

But the real action is at the state level, where state governments are looking to encourage nuclear projects—first, to ensure businesses have the clean, reliable power they need at competitive prices, and second, to ensure that the state secures the high-quality jobs that nuclear plants bring.

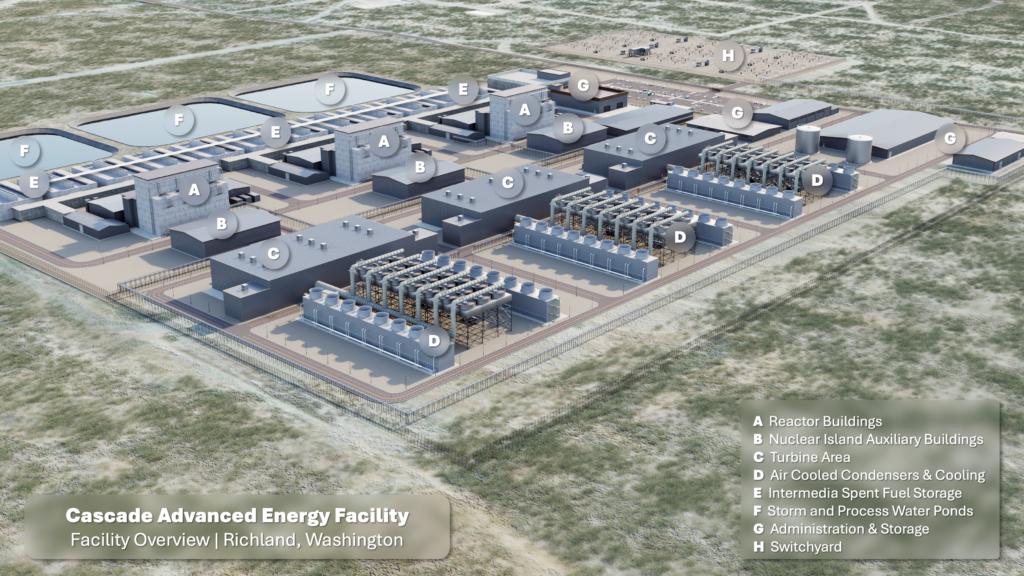

Several U.S. states have begun to offer incentives or have set aside placeholders in their budgets for the industry. For example, the governor of Virginia recently signed a bill to accelerate the development of small modular reactors (SMRs) in the state, with plans to have at least one built by 2030. There are also plans for new SMRs next to an existing plant in Washington state, with some support from the state legislature.

Meanwhile, officials in Texas are working hard to attract new nuclear projects to the state, with plans under consideration at universities in the state and on other sites. In Tennessee, regulators have issued exemptions that will aid the progress of two high-temperature reactors planned for the Oak Ridge National Laboratory site, which has also been earmarked as the location of a new uranium enrichment facility.

The recent activity at the state level is on top of the strong support from the Federal government, which, through the DOE, is supporting several demonstration projects across the country. These include the TerraPower project in Wyoming, X-energy’s project with Dow Chemical in Texas, and several others.

Only a few years ago, in the U.S., we were working just to keep existing reactors on the grid. Today, that danger has passed. Reactors previously under threat of closure are staying open. We are seeing a complete about face with reactors already closed, with some, like Three Mile Island—now slated to reopen. Administration officials acknowledge there are several others under consideration for restart. And there are a growing number of plans to build new nuclear facilities.

As tech companies build new data centers to power AI and other power-hungry activities, there is new demand for reliable, carbon-free power, which nuclear plants are best at providing. We can all see that the demand from such centers is set to increase further in the future. Meanwhile, major industrial end-users like steel, oil, gas, and chemical companies have begun considering nuclear and have launched demand aggregation to build order books for new nuclear power plants.

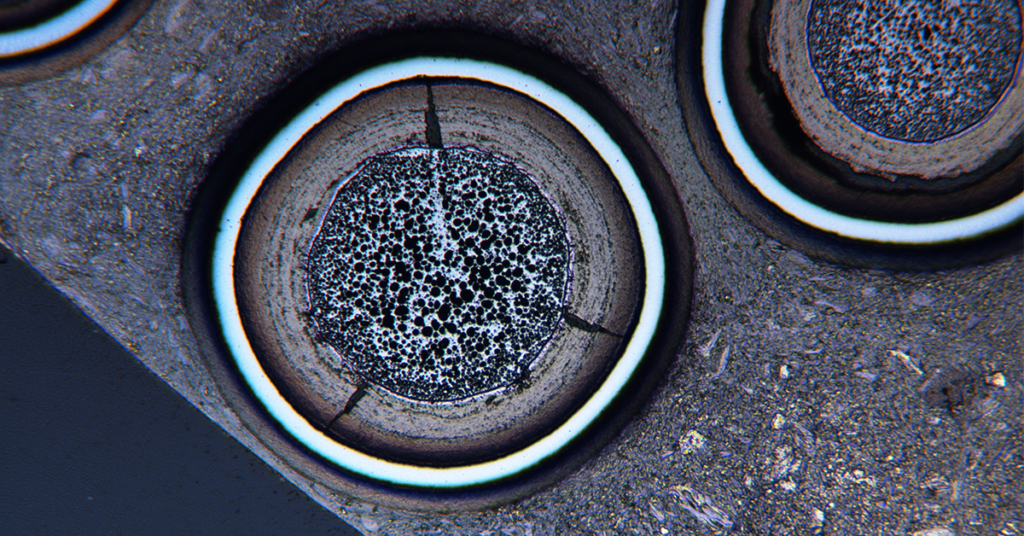

Some advanced nuclear technologies operate at high temperatures, making them very good at servicing industrial applications such as producing hydrogen or ammonia. Their high-temperature operation makes them excellent choices to replace coal plants, because they can sometimes use the same turbines as well as other infrastructure such as grid connections.

Of course, new nuclear designs must prove themselves cost-competitive with other energy sources. The U.S. has gained hard-won experience building Vogtle 3 and 4, and estimates are that the next AP1000 could achieve a 25% cost reduction. Evidence from around the world shows us that substantial cost reductions are achievable once we get to an “nth-of-a-kind reactor,” and once local workforce supply chains are built out and secure.

DOE’s updated version of its liftoff report provides practical advice on how to reduce the cost of building nuclear plants. “Delivering the first projects reasonably on-time and on-budget will be essential for achieving liftoff of the next wave of nuclear in the U.S.; Vogtle provides essential lessons for project delivery,” the report notes.

In addition, U.S. nuclear companies are seeing new international opportunities and are looking to complete their first project domestically before pursuing the new projects abroad. While many potential customers are interested in U.S. technology, coupled with the trust they have in the long-established U.S. nuclear sector, they all want to see a project completed before signing on.

Meeting the anticipated demand for new nuclear will require more than construction experience. This growth will also require specialized training and overall workforce development. We need to do more—globally—to ensure we have a suitably skilled extensive workforce to keep up with the demand.

We know that when we build nuclear plants, we don’t just build reactors. We build the engines of a cleaner economy. We build supply chains. We build capability. We build sustainable futures.

There is a beautiful irony that the recent news from Three Mile Island—a site once seen as casting a shadow over the nuclear sector in the U.S. and beyond—could, in fact, mark a major turning point in the sector’s resurgence.

—Todd Abrajano is president and CEO of the U.S. Nuclear Industry Council.