Everywhere you turn these days people are talking about data centers and the enormous amount of electrical power they are expected to demand as artificial intelligence (AI) platforms scale up and become more widely used. According to research conducted by Goldman Sachs, a ChatGPT query requires nearly 10 times as much electricity to process as a Google search. The firm estimates that data center power demand will grow 160% by 2030 as the AI revolution continues to gain momentum in coming years.

Nuclear Power to the Rescue

Tech companies recognize the dilemma, and several have acted to begin sourcing power for their data centers. For several, nuclear energy has been the resource of choice for its baseload and reliable power attributes. In September, Microsoft struck a deal with Constellation that could restart the Three Mile Island (TMI) nuclear plant in Pennsylvania. The 20-year power purchase agreement (PPA), if approved by regulators, will allow Microsoft to buy all the power from TMI’s 835-MW Unit 1. The plant was officially closed in 2019, but Constellation said it could be returned to service by 2028, if plans move forward as expected.

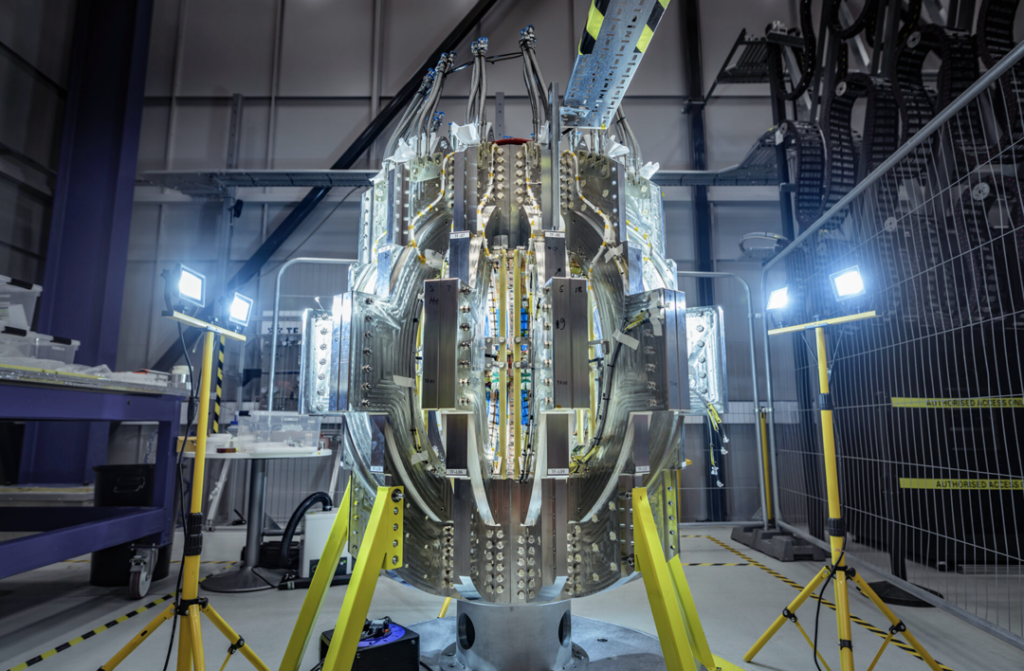

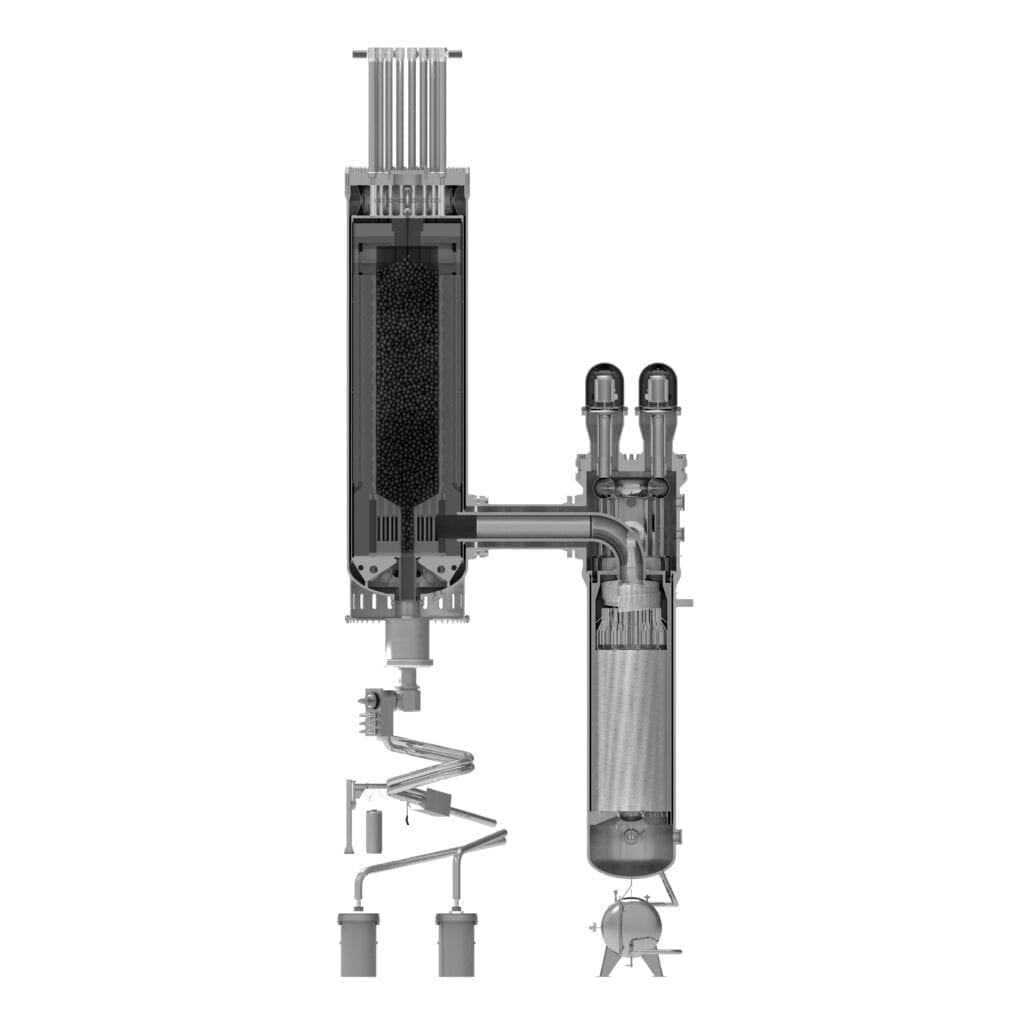

Meanwhile, Google and Amazon are pursuing new nuclear units of the small modular reactor (SMR) ilk. In a deal Google signed with Kairos Power in October, a 500-MW fleet of fluoride salt-cooled high-temperature reactors will be developed, constructed, and operated by Kairos Power, with the plants’ energy, ancillary services, and environmental attributes sold to Google under PPAs. The plants will reportedly be sited “in relevant service territories to supply clean electricity to Google data centers,” with the first deployment by 2030. Additional units are expected to be brought online through 2035.

Amazon and X-energy are also collaborating, in their case, to bring more than 5 GW of new power projects online by 2039. Called “the largest commercial deployment target of SMRs to date,” the companies will initially support a four-unit 320-MW project with regional utility Energy Northwest in central Washington. The reactors will be constructed, owned, and operated by Energy Northwest, and are expected to help meet the forecasted energy needs in the region beginning in the early 2030s.

In a separate deal announced the same day, Amazon said it signed a memorandum of understanding with Dominion Energy to explore the development of a 300-MW SMR project near Dominion Energy’s existing 1,892-MW North Anna nuclear power station in Virginia. The area is ripe with data centers; Virginia hosts “the largest data center market in the world,” according to the Virginia Economic Development Partnership. It is reportedly home to 35% of all known “hyperscale data centers.” The agreement is expected to help Dominion Energy meet future power demand, which is expected to increase by 85% over the next 15 years.

Data centers powered by these projects won’t be the first in Amazon’s portfolio to use nuclear power. In March, Amazon Web Services (AWS) bought the Cumulus data center campus in northeast Pennsylvania from Talen Energy. That site is powered by Talen Energy’s Susquehanna nuclear power plant, and AWS has long-term agreements with the company to continue powering the campus directly from the plant.

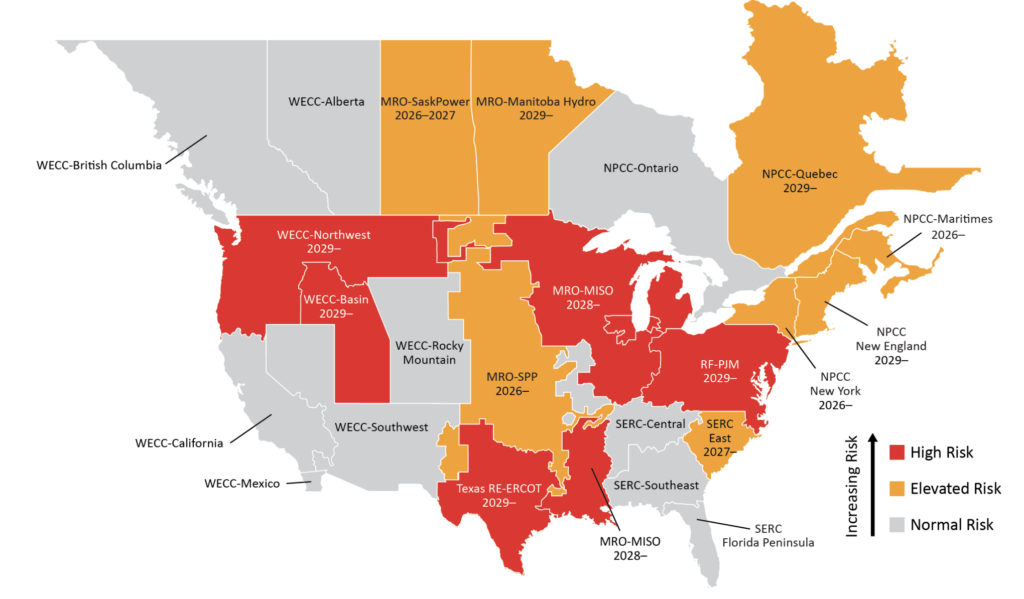

Siting in Areas with Available Capacity

Sheldon Kimber, founder and CEO of Intersect Power, suggests the concept of “power first” when he talks to data center developers. In other words, they should start with the availability of power as the first criteria when siting a new data center, and screen out sites that don’t have the required power. Kimber said placing a data center near an existing wind and solar project in the panhandle of Texas, for example, could be much easier and cost-effective in the long run than trying to site a renewable or nuclear project near a data center hub, such as in Virginia.

“The realization that the grid just isn’t going to be able to provide power in most of the places that people want it is now causing a lot of data center customers to re-evaluate the need to move from where they are, and when they’re making those moves, obviously, the first thing that’s coming to mind is: ‘Well, if I’m going to have to move anyway, I might as well move to where the binding constraint, which is power, is no longer a constraint,’ ” Kimber explained.

Efficiency Improvements a Wildcard

Yet, not everyone believes data centers are going to require the vast amounts of energy often touted. Amory Lovins, adjunct professor and adjunct lecturer in Civil and Environmental Engineering at Stanford University, and co-founder and chairman emeritus of RMI (founded as Rocky Mountain Institute), claims data centers have two to three orders of magnitude efficiency opportunities, combining hardware and software solutions.

“I think help is on the way, and there’s history behind this,” Lovins said during a press briefing hosted by Hastings Group Media in early October. “[From] 2010 to 2018, the amount of data center computing done—in, I believe it’s the world—rose by 550%, and the electricity they used to do that rose by 6.5%. In other words, the efficiency gains almost completely offset the growth in activities.”

Lovins said the last data center design he worked on was able to triple the efficiency at normal construction cost. Notably, his partner, EDS, said, had the client followed all of the team’s advice, it would have saved 95% of the energy and half the capital cost.

“If you look at the NVIDIA website, you will be startled [to find] about two to four orders of magnitude gains in system efficiency in each generation of their chips and firmware—that’s already happened and a lot more like that on the way.”

—Aaron Larson is POWER’s executive editor.