The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) proposed changes to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations to promote “efficient, effective, and timely” NEPA review by federal agencies (85 Fed. Reg. 1684 / Jan. 10, 2020). The changes would radically alter what federal agencies consider when assessing the environmental impact of agency actions. A necessary improvement, the proposed changes would streamline energy development projects mired by the drawn-out, costly, and unworkable NEPA procedure. But given remarkable opposition to the reform, whether the changes will provide much-needed business certainty or create additional ambiguity in the NEPA review process remains to be seen.

COMMENTARY

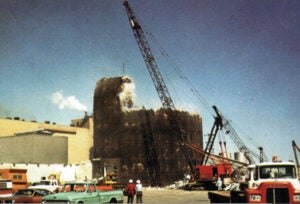

Congress enacted NEPA to be a bare-bones procedural statute designed to ensure that agencies “look before they leap.” Without dictating a substantive result, the statute requires federal agencies to consider significant environmental consequences of “major federal actions” (including an agency’s decision to permit an energy project and alternatives to that project) while both informing and providing the public with an opportunity to comment on the agency’s environmental analysis. Overly prescriptive regulations written more than four decades ago have led to unnecessary complexity, a plethora of litigation, and prolonged delays in both the permitting process and project construction.

A Red-Tape Weapon

Project antagonists, and agencies opposed to energy and other infrastructure projects, have abused the regulations as a red-tape weapon against project developments. CEQ’s sweeping changes would significantly reduce the time it takes to publish an Environmental Assessment (EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), reducing the significant delays that have historically strangled commercial, energy, and transportation-related development. The welcome changes attempt to reign in agencies conducting far-reaching NEPA review beyond their “limited jurisdiction” and refocus agencies on analysis that informs site-specific decisions.

The most important proposed change would modify the definition of “effect.” The scope of NEPA review depends on the “effects” of agency action. The modification would eliminate the requirement to consider indirect and cumulative effects of agency action, and instead limit consideration to effects temporally and geographically related to the action. The proposed rule would ensure that agencies focus their attention on effects that are “reasonably foreseeable” and have a “reasonably close causal relationship” to the proposed action.

Modifying the definition of “effect” is a significant change. Although silent on greenhouse gases, the change would arguably preclude agencies from considering a proposed action’s effect on climate change, including upstream and downstream effects. The proposed rule targets judicial decisions blocking energy infrastructure development by requiring permitting agencies to consider the cradle-to-grave effects of a project on climate change.

Page and Time Limits

The proposed changes would also place page and time limits on NEPA review documents. The average length of an EIS with appendixes is more than 1,000 pages. The proposed rule would presumptively establish a 75-page limit for EAs and clarifies that an agency does not need to include a detailed discussion of each alternative in an EA, nor does it need to include a detailed discussion of alternatives it eliminated from study. In contrast, an EIS requires a detailed analysis of all significant environmental effects, which the proposed changes would limit in most cases to 300 pages. The proposed rule would address the average waiting period of more than four years by establishing one year as the presumptive timeframe for issuance of an EA, and two years as the presumptive timeframe for an EIS.

Other notable changes would allow applicants a greater role in preparing NEPA documents, allow agencies to determine that compliance with the environmental review requirements of other statutes serves as the functional equivalent of NEPA compliance, require agencies to prepare joint NEPA documents when practicable, and expand the use of categorical exclusions by considering mitigating circumstances.

Opposition to the dramatic shift in both the process and substance of NEPA review proposed by the rulemaking will inevitably invite litigation from climate activists and green states where proposed fossil fuel development projects are currently undergoing contested permitting processes. Paradoxically, these rules, if finalized, could spur investment in and permitting of renewable wind, solar, hydroelectric, and other alternative energy projects, which individually and collectively help combat the effects of climate change.

A prolonged legal battle in multiple venues could end up in the hands of the nation’s highest court. Democrats have pledged a swift legislative response to the proposal, perhaps invoking the dormant Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to overrule a regulation by joint resolution.

CEQ has invited public comments to be submitted by March 10, 2020, although members of Congress and environmental activists are currently lobbying for additional time in light of the vast number of comments expected and the sweeping changes proposed. Given that this is an election year, stay tuned, as the Trump administration is racing against the clock to finalize the rule before the November election. ■

—Beth Ginsberg is a partner at Stoel Rives LLP where she litigates natural resource, wildlife, and environmental cases, and counsels clients on the complexities of regulatory compliance and permitting issues. Max Yoklic is an associate in Stoel Rives’ Environment, Land Use & Natural Resources group.