The federal government’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) on Oct. 7 issued a proposed rulemaking to rescind several Trump-era regulatory amendments that limit the scope of environmental reviews completed by federal agencies under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). If finalized, the proposed rule would restore agencies’ discretion to broaden the scope of NEPA reviews.

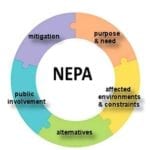

NEPA is a procedural law that requires federal agencies to consider the environmental, cultural, aesthetic, and other impacts of their proposed actions, including permit approvals for energy and related infrastructure projects. These requirements are intended to ensure that both federal agencies and the public are adequately informed about the anticipated impacts of a proposed agency action before the action occurs.

COMMENTARY

CEQ, which is within the executive office of the president, “coordinates the federal government’s efforts to improve, preserve, and protect America’s public health and environment.” In this role, CEQ has adopted NEPA regulations to guide federal agencies’ implementation of NEPA. As a supplement to CEQ’s regulations, many federal agencies have adopted their own NEPA regulations based on their unique roles, responsibilities, and organizational structures.

During the Trump administration, CEQ finalized a comprehensive set of regulatory changes to its 1978 NEPA regulations (the 2020 NEPA Rule). Under the Biden administration, CEQ has been reviewing the 2020 NEPA Rule to determine which of its parts will be rescinded or otherwise amended.

The Proposal

The new proposal, which is the first of two anticipated NEPA rulemakings by CEQ, would make only a handful of regulatory amendments. With that said, these narrow amendments would have considerable impacts on environmental reviews when compared to the 2020 NEPA Rule, and these impacts would have meaningful implications for energy projects.

Purpose and Need. First, the proposal seeks to restore CEQ’s past regulatory language governing the “purpose and need” for proposed agency action found in 40 C.F.R. §1502.13. Defining the “purpose and need” for a proposed action is, in large part, the crux of NEPA reviews because it cabins the range of reasonable alternatives and the scope of environmental impacts an agency will consider. The 2020 NEPA Rule modified the originally broad regulation by requiring agencies to “base the purpose and need on the goals of the applicant and the agency’s authority.”

According to CEQ, the 2020 NEPA Rule’s language improperly limits the statement of purpose and need to the applicant’s goals and thereby excludes other important factors, including the public interest, regulatory requirements, desired conditions on landscape or other environmental outcomes, and local economic needs. The proposal therefore would restore the preexisting regulatory language, providing that “[t]he statement shall briefly specify the underlying purpose and need to which the agency is responding in proposing the alternatives including the proposed action.” Based on this change, the proposal would make corresponding revisions to the regulatory definition of “reasonable alternatives.”

“Effects” Definition. Second, the proposal substantively would restore CEQ’s past regulatory definition of “effects,” which addresses direct, indirect, and cumulative effects. The 2020 NEPA Rule made numerous changes to the definition of “effects” intended to limit the scope of environmental impacts agencies consider when completing environmental reviews, and presumably to accelerate the NEPA-review process as well as protect agency decisions against frequent NEPA challenges in this area.

To do this, the 2020 NEPA Rule defined “effects or impacts” as “changes to the human environment from the proposed action or alternatives that are reasonably foreseeable and have a reasonably close causal relationship to the proposed action or alternatives ….” Further, the definition states that “[e]ffects should generally not be considered if they are remote in time, geographically remote, or the product of a lengthy causal chain,” and that “[e]ffects do not include those effects that the agency has no ability to prevent due to its limited statutory authority or would occur regardless of the proposed action.” In addition to these changes, the 2020 NEPA Rule also eliminated the definition of “cumulative impacts,” which refers to incremental environmental impacts from an action combined with the impacts of past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions.

If finalized, the proposal would eliminate the 2020 NEPA Rule’s definitional provisions that limit the scope of impacts an agency can consider and reinstate the definition for “cumulative effects.” According to CEQ, restoring these provisions would “ensure that the NEPA process fully and fairly considers the appropriate universe of effects, such as air and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change, and effects on communities with environmental justice concerns.” As to “cumulative effects,” CEQ observes that “aggregate air and water pollution and habitat impacts affect long-term environmental conditions, wildlife, and communities—including in regions already overburdened by pollution.”

In the proposal, CEQ also indicates what restoring the “effects” definitional provisions means for energy projects. For example, CEQ acknowledges that restoring these provisions will allow agencies to consider the indirect, long-term beneficial effects of renewable energy projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by displacing “greenhouse gas-intensive energy sources (such as coal or natural gas) as an electricity source for years or decades into the future.” Consideration of these remote, long-term benefits could be very beneficial for renewable energy developers. For example, agencies could rely on such benefits as a basis for adopting new categorical exclusions or taking other actions that could accelerate NEPA reviews for renewable energy projects.

Separately, the proposal indicates what CEQ is thinking about the analyses of effects related to fossil fuel activities. For example, the proposal provides that “pollution, including greenhouse gas emissions, released by fossil fuel combustion is often a reasonably foreseeable indirect effect of proposed fossil fuel extraction that agencies should evaluate in the NEPA process.” The proposal also indicates that such analyses may be appropriate even where an agency does not exercise control or regulatory authority over all aspects of a project. According to CEQ, “consideration of such effects can provide important information on the selection of a preferred alternative.” As an example, CEQ states that “an agency decision maker might select the no action alternative, as opposed to a fossil fuel leasing alternative, on the basis that it best aligns with the agency’s statutory authorities and policies with respect to greenhouse gas emission mitigation.”

Ceiling Provisions. Finally, the proposal would eliminate the 2020 NEPA Rule’s ceiling provisions, which generally prohibit federal agencies from adopting their own NEPA regulations that impose procedures beyond CEQ’s requirements. Under the proposal, agencies would have the discretion and flexibility to develop procedures beyond what CEQ has established to, among other things, “address their specific programs and the contexts in which they operate.” CEQ states that this has been the council’s longstanding understanding and practice.

Conclusion

Besides restoring impactful regulatory provisions that existed before the 2020 NEPA Rule, the proposal gives industry and the public a good insight into how the Biden administration plans on implementing NEPA. The proposal, for example, is laden with statements hinting at robust analyses of impacts related to climate change and environmental justice. Relatedly, it highlights an example where a federal agency could select the “no action alternative” instead of a proposed action related to fossil-fuel leasing (the Bureau of Land Management is currently undergoing a review of its coal-leasing program.). In short, the writing is on the wall when it comes to NEPA reviews, and power companies will need to plan and adapt accordingly.

—Jared Wigginton is an experienced environmental, natural resources, and energy attorney committed to advancing renewable energy and related infrastructure projects by assisting businesses with permitting, regulatory advocacy, litigation, and enforcement matters. To help fulfill this commitment, Wigginton founded Good Steward Legal, a principles-based business law office dedicated to protecting and advancing its clients’ interests by providing them with cost-effective, high-quality legal service.