With the advance of natural gas, increasing regulatory challenges, and anti-coal politics, U.S. coal-fired power plants are facing unprecedented retirements. A key question is what to do with them once they have shut down.

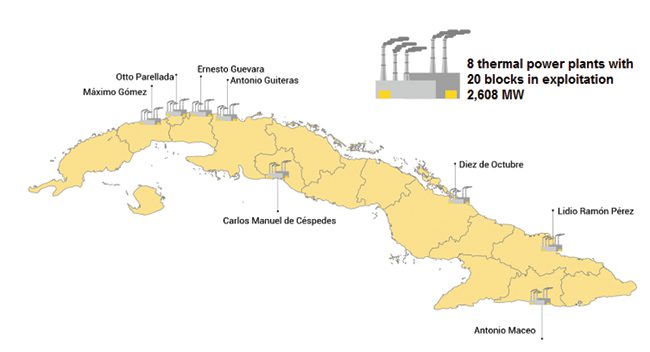

Austin, Texas, is one of the hottest real-estate markets in the U.S. One of the prime new properties in the Texas capital is Seaholm, a $130 million project on some eight acres of prime downtown land, featuring residential, office, and retail space on the southwestern edge of the city (Figure 1). Next door will be a new public library. The development’s website notes that the site is an “architectural gem built in the 1950s.”

|

| 1. Urban gem. Austin Energy’s former Seaholm Power Plant, which once burned coal, is being repurposed as the centerpiece of a redevelopment plan. Courtesy: Austin Energy |

What may be more significant is that this gem is the site of a former coal-fired power plant, with a handsome Art Deco–Art Moderne building, once a key generating plant for Austin’s municipal electric utility. The plant was designed in two phases in 1948 and 1955, under the direction of the noted Kansas City engineering firm of Burns & McDonnell, and named for Walter Seaholm, long-time Austin city manager.

The plant ran on coal for many years, then switched to fuel oil and natural gas, and went into standby service in 1989. It finally shut down for good in 1996. The Austin muni started thinking about demolishing the plant in 2006, but many in the community wanted to save the plant’s distinctive shell and its unusual and attractive design. A grassroots movement saved the structure, which is now part of a major urban redevelopment project.

Austin’s Seaholm story is a positive example in what has become a major new trend in energy: dealing with old, uneconomic coal plants.

Big Business

Demolishing and decommissioning coal-fired power plants, once a small part of the energy landscape, has become a big deal in recent years, driven by the economics of cheap natural gas and the march of environmental regulation across the generating landscape. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the congressional watchdog agency, since 2012 generators have retired or announced retirements of some 42 GW of coal-fired capacity—roughly 13% of the nation’s coal-fired fleet. Two years ago, the GAO predicted between 2% and 12% for coal plant retirements by 2025.

The GAO said between January 2012 and May 2014, 15 GW of summer coal-fired capacity had been retired. The Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration has even higher estimates of coal plant closings, some 50 GW—or 16% of capacity—from 2012 through 2020. About three-quarters of the retirements will occur by the end of 2015.

An analysis a year ago by Navigant Research found, “While retirements will occur in many countries, the majority will take place in North America and Western Europe, as countries in Asia Pacific, for example, continue on a path of major coal generation additions in the next two decades. Navigant Research forecasts that the market for coal plant decommissioning in North America and Europe will grow from $455 million in 2013 to $1.3 billion by 2016, declining rapidly thereafter. Cumulative revenue from 2013 to 2020 will total $5.3 billion.”

Chris Dowdell, a business development manager at the eastern office of Brandenburg, a veteran demolition firm, told POWER that his company views retired coal-fired power plants as a major business opportunity. “It started in 2009–2010,” he said, “and we are hitting a peak right now, looking at the 2015–2016 period.” He said his company is actively bidding on some 20 coal decommissioning projects. Brandenburg has been in the demolition business for 40 years and has been working with power plant projects for the last 30 years.

Brandenburg’s eastern office, located in Bethlehem, Pa., is well positioned to play in the market for coal plant demolition and decommissioning. Ironically, the company is located quite close to the headquarters of the PJM Interconnection, a few miles south of Bethlehem in the historic town of Valley Forge. PJM’s market players in the East and Midwest have announced a large number of coal plant closings. But Brandenburg isn’t making a big play for those jobs.

PJM’s deregulated, competitive wholesale market is an economic hurdle for plant owners, as they have to cover the full costs of the job themselves. Instead, explains Dowdell, Brandenburg is focusing on the southeast, where conventional regulation still prevails. “That region presents better opportunities,” he said, “because utilities can go to their public utility commissions and have the costs of the demolition project built into customer rates, so the consumer helps pay the costs.” Last May, for example, Duke Energy announced it would retire five coal-fired units in Florida, on top of earlier announcements of coal retirements in the Carolinas.

Duke’s website notes, “By the end of 2013, Duke Energy retired units at nine coal-fired generation sites in the Carolinas. The long-term vision for sites with retired coal units across our system is to return them to ground level. During the early stages of the decommissioning and demolition project, we will remove chemicals and other materials, salvage what equipment we can recycle and repurpose at other sites and sell any scrap material. In the demolition and restoration phases, we will safely remove the powerhouse, chimneys and any auxiliary structures no longer needed and then fill, grade and seed the land.”

Lots to Consider

Once a company makes a decision to retire a plant, says Jeff Pope of Burns & McDonnell, the company faces a series of choices. “First you need to address what decommissioning means,” he says. “Do you really want to tear it down? Take more of an ‘abandon in place’ approach and keep additional units running at a given site? Or simply leave the abandoned asset in place, depending on the market for scrap metal?”

Taking a coal plant down is fairly straightforward—and no radiation complicates the job, as with nuclear decommissioning. The list of hazardous materials is generally predictable. Burns & McDonnell notes, “Asbestos abatement must occur before any demolition. Remediation also involves lead abatement and PCB and mercury contamination removal where necessary.”

But there can be surprises of a sort that don’t show up in nuclear work, notes Rick Scadden at INTERA, a Texas-based engineering firm. As he explained to POWER, toxics can show up in unexpected places, and engineers involved in decommissioning often have to rely on memories of former plant workers to help locate problems. Over the years, noted Scadden, many plants have been renovated, and renovated again. During that work, asbestos was routinely and freely used around areas that might face the risk of fire.

“You can find strange things,” Scadden said. “Old transformer oil, loaded with PCBs, was used to lubricate moving equipment such as rotating screens. So you get PCBs in places you would never think of. Sometimes, PCBs were used in paint, to extend the paint. So you get paint that has got to be remediated on walls of the turbine room 40 feet off the ground.”

Says Scadden, “A lot is dependent on the original design and how well the plant was maintained, and the documentation for that.” Quality assurance and quality control programs 50 years ago weren’t the priority they are today. “Some plants are in great shape, with little contamination,” notes Scadden. “Others, not so. One of the things we have done is go back to former employees, get some of them in the same room together. They know a lot of stuff about those old plants, and they like talking about it.”

More Than One Option

Often, repowering a retired plant can be the best option. “Repowering a plant with gas-fired elements can make sense because so much of the infrastructure is already in place, including transmission lines, substations, and water,” says Burns & McDonnell’s Jeff Kopp. “Can you retrofit existing equipment, either by converting the boilers to burn gas or installing a combustion turbine in combined cycle with existing steam turbine? Can you rescue the site by using all-new equipment and take advantage of existing infrastructure? Or do you abandon the site altogether and build elsewhere?”

Calculating the economics can be tricky, which has caused some trepidation among plant owners contemplating the costs of retiring coal-fired units. As the industry gains experience, the economics are likely to become clearer. Brandenburg’s Dowdell says, “Over time, companies are becoming more educated. They were really afraid that the process would cost a lot of money. But with the credit for scrap, projects aren’t as costly as feared.”

That matches the experience of Burns & McDonnell. Kopp said a study that a demolition contractor did for a plant decommissioning a few years ago overlooked the scrap value. “This dramatically changed the net demolition costs for that facility because we were able to uncover several million dollars in credit.”

Regulatory Thicket

In addition to engineering challenges, decommissioning an old coal plant also presents legal and regulatory hurdles, writes Nixon Peabody lawyer Bruce Baker in a company blog. “Options are limited. Risks are high. Money is scarce. Between the [Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)] air toxic emissions regulations and the millions of dollars needed to modernize equipment to meet standards, a wave of power plants are being forced to shut down. And when that happens, a cascade of legal consequences follows.” The firm says its experience has ranged from “construction contracts to meeting stringent environmental requirements, finding strategies for maximizing salvage credit, evaluating redevelopment options and tax incentives, and minimizing and resolving litigation threats and construction disputes.”

Some outstanding regulatory issues complicate many coal-plant decommissioning plans. The one that causes the most head scratching is coal ash disposal, where new EPA rules have been pending for years. The EPA is due to issue new rules for handling ash under the terms of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act this month, which may provide some clarity (see “Be Prepared for Coal Ash Regulations” in the March 2014 issue and “Construction Considerations Are Key in Closure Planning for Coal Ash Ponds” in this issue).

For its part, Duke has faced particularly difficult problems with ash ponds at retired coal-fired plants. Last February, a major leak from an ash pond sent tens of thousands of tons of ash into the Dan River in North Carolina. Inspectors later discovered a crack in the dam holding back an ash pond at another retired coal plant.

Duke says it “is committed to effectively closing ash basins once they are no longer needed, with approval from state regulators. We have been evaluating multiple closure options to ensure we select a method that protects groundwater long term and is prudent for our customers and plant neighbors. In light of the Dan River ash release event, we are taking another look at all of our ash basins across the fleet. Before this event, our focus was on closing ash basins at the recently retired coal plants in North Carolina. This remains a high priority, and we will work through those steps with regulatory and legislative input to ensure our decisions protect the environment and our communities.”

It’s clear that coal decommissioning has become a major topic among generating companies. Burns & McDonnell’s Pope said, “Most of the owners in the power industry have been building all these years, or repowering or modifying their facilities. This is the first time they’re actually looking at having to take these units down.” ■

— Kennedy Maize is a POWER contributing editor.