When you hear “drone,” do you think, toy, military craft, dangerous device, or useful tool? Depending on the type of unmanned aircraft system (aka, drone) we’re talking about, any of those descriptors (or multiple ones) could be appropriate. Drones were a hit under Christmas trees last December, they’re a now-common weapon delivery system, and they also—as you’ll see in this issue’s cover stories—are beginning to play useful roles in industry.

Technology’s Role in Energy Transitions

We usually think of novel technologies as introducing “solutions,” but many also introduce fresh challenges, like new privacy and safety issues raised by the increasing recreational and commercial use of drones.

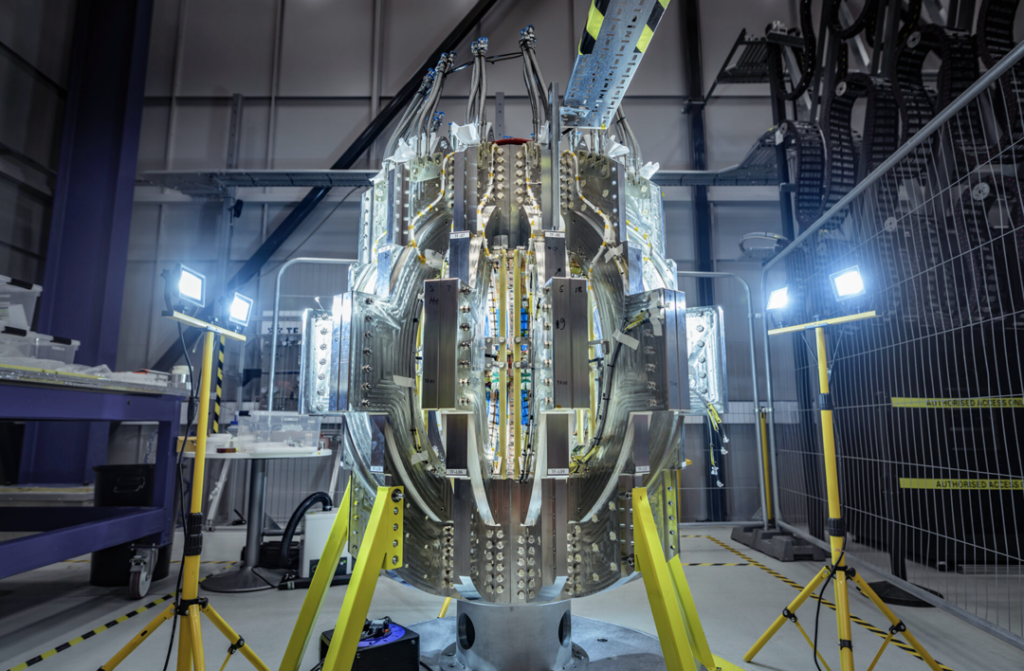

At IHS CERAWeek in late February, when Exelon CEO Chris Crane was asked what energy industry leaders would be talking about at CERAWeek 2020, he responded that discussions would be about the surprising technology that has transformed the industry. Of course, technology has already transformed the energy industry a few times. Nuclear power, with which Crane is very familiar, was the biggest new technology transformation for the power industry in the last century. We’re currently in the midst of another transformation, this one involving wind and solar power plus new forms of energy storage. And then there’s hydraulic fracturing, which has transformed global oil and gas markets—an issue that was the pervasive theme of this year’s CERAWeek.

The conference’s official theme was “Energy Transitions,” but a more apt one would have been “How Fracking Flipped Winners and Losers.”

CERAWeek attracts headliners from around the world, and this year, regardless of which continent the speakers hailed from, it was clear that the balance of power in the energy sector has shifted. Though shale resources have been a topic of conversation for the past few years at “the Davos of energy,” in 2016 it was clear that we’re actually beyond the transition stage; the dynamics have changed. Though still important, OPEC no longer holds all the cards. Fracked natural gas and oil have upended global commodity prices and supply chains, as was demonstrated—with serendipitous timing—when the first tanker carrying liquefied natural gas left a U.S. port, headed for Brazil, on “gas day” at the event.

Fracking technology has been a boon for the U.S. economy and consumers, but, as several speakers pointed out, there are negative consequences of unanticipated supply shifts. Among them is the fact that global oversupply of oil and gas has led to reductions of as much as a third in research and development (R&D) as well as in developing new plays. Sooner or later, the multimillionaire experts agreed, the cycle will turn, prices will spike, and the resources may not be there as quickly as required.

Of Climate Change and Fossil Fuels

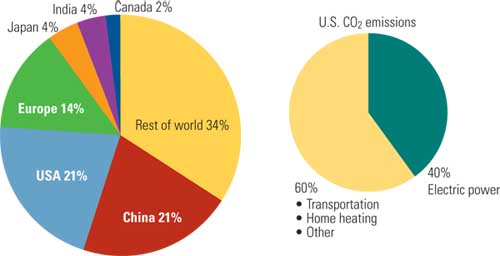

Another discussion thread at CERAWeek concerned responses to climate change in light of what most participants saw as a positive outcome from the Paris talks in December. Natural gas, thanks to fracking, is seen as the near-term “transition path” to a lower-carbon energy system. Whether in reference to oil, natural gas, or coal, every speaker who addressed the issue explicitly or implicitly said that leaving remaining fossil fuels in the ground (as some Paris participants had suggested) is not an option—no surprise, as CERAWeek focuses almost exclusively on fossil fuels.

At the same time, there were no climate change deniers at the event. So if there’s agreement that the world needs fossil fuels but also needs to counteract their greenhouse gas (GHG) effects, is carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) the technology we’ve all been waiting for?

CCS: Magic Bullet or Blank?

In contrast to virtual consensus about the effects of fracking on global markets, opinions about the viability of CCS varied substantially. Here’s a sampling of the energy experts’ comments:

■ International Energy Agency (IEA) Executive Director Fatih Birol: CCS “can be a very important asset-protection strategy,” yet the “appetite” for CCS is not as strong as it should be.

■ General Electric Chairman and CEO Jeffrey Immelt: “It’s going to be a struggle.”

■ Minister of Petroleum & Mineral Resources (for Saudi Arabia) Ali Al-Naimi: “For the record, we recognize the threat posed by climate change” and are investing in CCS and renewables.

■ Centrica (UK) CEO Iain Conn: “I’m quite sure that clean coal is a miss.”

From where I sit (in the cheap seats), CCS has been a case of the tail wagging the dog. The only time post-combustion carbon capture from power plants is even being looked at (outside of government-sponsored pilots) is when there’s a plan to partially offset capture costs through sales of compressed carbon dioxide (CO2) for enhanced oil recovery (EOR). Not surprisingly, the oil and gas industry is a much bigger fan of CCS than power generators are. Until more economic and varied uses can be found for CO2 captured from power plants (see this month’s Commentary for one effort to encourage such development), CCS increases hydrocarbon extraction efficiency at the cost of power generation efficiency.

Faith Must Lead to Action

So, can technology—a better type of CCS and/or new forms of energy conversion and storage—save the world from unmanagable climate change while ensuring energy access and economic prosperity for all? By 2020?

The IEA’s Birol said he has “faith in the power of technology” to solve the fossil fuel/climate change conundrum. I’d like to believe we can develop technology solutions to our energy and climate challenges, but today it seems that certain end users (fossil power generators) are paying a higher price for participating in the fossil fuel economy than market participants further upstream.

While commodity prices are low, oil and gas and coal mining companies could be diversifying through R&D of carbon-mitigation technologies. It’s long past time for upstream energy companies to demonstrate substantive commitment to climate change solutions—other than CCS-to-EOR—that reduce the carbon footprint across the energy sector. ■

—Gail Reitenbach, PhD is editor of POWER.