The number of companies pulling out of the nuclear business continues to grow. Just weeks after Louisiana-based engineering firm The Shaw Group announced it would sell its 20% stake in the nuclear company Westinghouse back to partner Toshiba, German engineering conglomerate Siemens said that, prompted by the German government’s decision to phase out nuclear power by 2022, it would quit the nuclear business. And in late September, UK company Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE) also said it may pull out of a joint venture with France’s GDF Suez and Spain’s Iberdrola to build a new nuclear power plant in West Cumbria, in northwest England, citing extended cost and development issues relating to new nuclear reactors.

Siemens built all of Germany’s 17 nuclear power plants. CEO Peter Löscher told German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel that, compelled by the Fukushima nuclear accident and its effect on German politics, the company would shut down all nuclear operations—including building any new power plants—and focus on the rapidly growing renewables sector. Alfons Benzinger, spokesman for Siemens Energy, however, told POWER in October that the company will continue to make conventional steam turbines to be used for nuclear plants and other conventional plants.

|

| 3. End of an era. Siemens, the German conglomerate that spearheaded nuclear technology development through the 1970s and 80s, is quitting its nuclear businesses, a decision shaped by the Fukushima crisis, which in turn prompted the German government‘s decision to phase out nuclear power by 2022. The company built all 17 nuclear plants in Germany. A Siemens worker is shown here fitting the blades of a low-pressure turbine. Courtesy: Siemens |

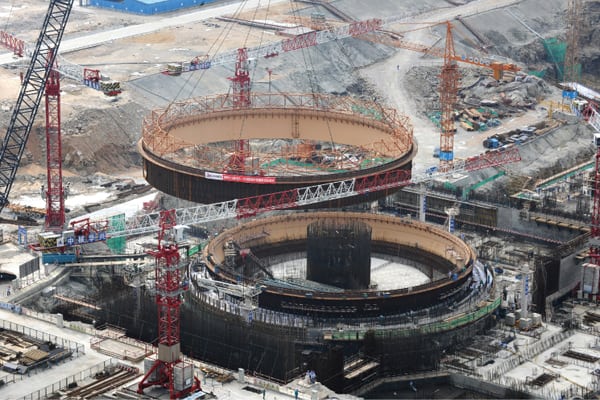

The German powerhouse’s decision to shed its nuclear businesses isn’t abrupt. Siemens spearheaded nuclear technology development through the 1970s and 1980s, but it began restructuring its reactor-making arm in 2001, when it merged that division, taking a minority 34% share, with French company Framatome—now known as AREVA NP. Framatome and Siemens developed the EPR in the 1990s before forming a joint entity (Figure 4). But that partnership ended in early 2009 when Siemens sold its share to AREVA, citing a “lack of exercising entrepreneurial influence within the joint venture” as the reason behind the move.

|

| 4. A product of past efforts. Siemens and Framatome, a company now known as AREVA, developed the third-generation EPR reactor that is currently under construction in Finland, France, and China. The two EPRs under construction at Taishan in China are on schedule. Unit 1 is expected to be operational in December 2013 and Unit 2, in October 2014. This image shows a crane lifting the reactor building liner. Courtesy: Sofinel |

Later in 2009, Siemens signed a memorandum of understanding with Russian state atomic energy utility Rosatom for the creation of a new nuclear joint venture that planned to push forward with development, marketing, and construction of Russia’s pressurized water reactor (VVER) technology—an agreement that was all but fruitless. This September, Rosatom inked an agreement with the UK’s Rolls-Royce (as part of a UK-Russia civil nuclear cooperation pact) to make use of that company’s large nuclear supply chain, including consultant activities, and manufacturing and technical engineering support. Rolls-Royce will also likely provide safety-critical instrumentation and control systems—as it has to all 58 operating nuclear facilities in France.

Providing safety-critical instrumentation and control systems for new reactors was part of Siemens’ specialist business unit, and the firm was also a specialist provider of the “conventional island” of new nuclear power plants. But, as World Nuclear News noted, most reactor vendors typically work with a regular partner or supply themselves for conventional island work: AREVA pairs with Alstom, for example; GE-Hitachi and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries supply themselves; Westinghouse works with several suppliers, including its owner Toshiba; and state-owned companies like Rosatom and South Korea’s KEPCO offer contracts to domestic firms. This has left the conglomerate with no defined partner for new nuclear builds—another factor that may have played into the firm’s decision to withdraw from nuclear activities altogether.

SSE—which has over 11 GW of coal, gas, and hydropower plants, as well as wind farms, across the UK and Ireland—had in October 2009 announced plans with GDF and Iberdrola to build a 3.6-GW nuclear plant near Sellafield, West Cumbria via a 25% stake in the NuGeneration joint venture. Those plans were buoyed by the UK government’s pending approval of eight sites for new nuclear builds—a strategy to ensure reliability because about a quarter of the country’s generation capacity is set to expire in the next decade as older reactors reach the end of their lives and coal plants are closed to meet European Union pollution standards. The company spent £19.5 million ($30.5 million) to secure the option to buy land for the development.

But SSE has since invested billions of pounds over the past two years in renewable projects, including the massive 350-MW land-based Clyde wind farm and the 500-MW Greater Gabbard offshore wind farm. SSE said in a statement in September that its decision to pull out of the nuclear joint venture was based on concerns relating to the “the cost, development issues, timetable and operational efficacy of nuclear power stations [that] all require the greatest possible scrutiny before a commitment to invest in new nuclear power stations can be made.” For the time being, the utility’s resources “are better deployed on business activities and technologies where it has the greatest knowledge and experience,” it said.

The Shaw Group’s decision to sell its stake in Westinghouse to Toshiba was prompted by a surge in its yen-dominated debt by almost $600 million to a total of $1.7 billion since its acquisition of Westinghouse in 2006. Paying off that debt increase would wipe out the expected gain from the stake sale—estimated at $545 million at the end of August—but it would leave the company with virtually no debt, the company said. The firm is expected to continue working with Westinghouse in the deployment and commercialization of the third-generation AP1000 reactors currently under construction in China and the state of Georgia, however.

—Sonal Patel is POWER’s senior writer.