NextEra Energy consists of a traditional, vertically integrated electric utility with a heavy reliance on nuclear and natural gas—Florida Power & Light—and an aggressive foray into renewable energy outside of Florida—NextEra Energy Resources. Given its recent bid for Hawaii’s electric utility, which has a legacy of oil-fired generation and a state commission pushing renewables, NextEra is clearly a company facing a generation transition.

The story of NextEra Energy is a tale of two companies, housed under the same corporate roof in Juno Beach, Fla., and about to add a third. One is a large, conventional, vertically integrated electric utility monopoly, Florida Power & Light (FPL), existing in the comfort of state regulation and reliant on nuclear and fossil generation. The other is NextEra Energy Resources, a nationwide competitive generation company focused on wind, solar, and nuclear generation—for many, an exemplar of the future of generation. On the far opposite side of the country lies Hawaii’s investor-owned electric system, which is poised to become the third company under the NextEra umbrella.

Though the first two companies have a solid track record, the third may prove to be a risky deal.

A Foundation of Traditional Generation

FPL’s regulated fleet consists of two nuclear units at St. Lucie, with 1,821 MW net capacity, two nuclear units and two gas units at Turkey Point with 3,186 MW net capacity, and 20,513 MW of mostly gas generation in operation elsewhere in the state. FPL has 3,800 MW of gas-fired capacity under construction. In 2014, according to the company’s earnings statement, FPL had $1.5 billion in net income, on $11.4 billion in sales, earning the company $3.45 per share.

FPL is the foundation and “cash cow” for NextEra Energy Resources, the company’s play in wholesale, unregulated markets. Energy Resources brought in $5.2 billion in revenue in 2014, with net income of $985 million ($1.89 per share) flowing to the parent’s bottom line. The resources company has about 19 GW of nameplate capacity in natural gas, wind, solar, and merchant nuclear in competitive wholesale markets. During 2014, it added 1,364 MW of wind and 265 MW of solar.

Talking to investment analysts late last year, NextEra Chief Financial Officer Moray Dewhurst said the company continues to invest in its regulated utility as Florida’s economy improves and the labor force grows, bringing steady load growth. Similarly, at Energy Resources, Dewhurst said, “Our development and construction programs remains on track and our backlog of contracted renewables projects continues to develop, with a [power purchase agreement] for another roughly 100 MW of U.S. wind signed since the last [earnings report]. Earnings growth was driven by new contracted renewables projects, as well as strong results in our customer supply and trading business.”

Energy Resources has inked about 980 MW in U.S. wind deals expected to enter service this year: the 249-MW Golden West and 150-MW Carousel projects in Colorado, a 99-MW project in Oklahoma, and another 482 MW in projects the company says it will announce later this year. The company brought over 1 GW of U.S. wind into service in 2014, and 340 MW in Canada.

Energy Resources is the largest U.S. generator of wind and solar power and growing rapidly.

Stretching to Embrace Hawaiian Utility

Last December, NextEra Energy announced a new direction, one that could turn out to be chancy. Joining the growing utility mergers and acquisitions trend (see “The Urge to Merge, or Vice Versa?” in the January 2015 issue), NextEra cut a $6 billion deal (including assumption of $1.7 billion in debt) to buy Hawaiian Electric Industries, which owns Hawaiian Electric Co. (HECO), which in turn owns Maui Electric and Hawaii Electric Light. The Hawaiian system is dominated by oil-fired generation (along with a 180-MW AES non-utility coal-fired plant) while seeing a boom in rooftop solar in its service territory. The company is under increasing pressure from state regulators to move more aggressively to renewables while reducing the cost of power to its customers.

In making the announcement that NextEra will buy Hawaiian Electric Industries, NextEra CEO Jim Robo said, “We are proud that Hawaiian Electric has agreed to join our company in large part because of our shared vision to bring cleaner, renewable energy to Hawaii, while at the same time helping to reduce energy costs to Hawaii Electric customers. Today, Hawaiian Electric is addressing a vast array of complex and interrelated issues associated with the company’s clean energy transformation.”

Connie Lau, Hawaiian Electric Industries CEO, said, “In NextEra Energy, Hawaiian Electric is gaining a trusted partner that can help the company accelerate its plans to achieve the clean energy future we all want for Hawaii. NextEra Energy and Hawaiian Electric share a common vision [of] a more affordable clean energy future for Hawaii.”

The announcement of the Hawaiian deal led Adam Browning, executive director of the grassroots advocacy group Vote Solar, to express skepticism about NextEra’s shining green image. Writing for Greentech Media, Browning noted the contrast between NextEra Energy Resources—“a renewable energy powerhouse and a credit to the nation”—and FPL, which he termed “a renewable desert.”

FPL, Browning said, is “a utility with 4.7 million customers—and only about 1,500 of them with solar on their roofs. While the utility’s TV ads prominently feature shiny solar energy projects, just 0.6 percent of FP&L’s energy mix comes from solar (leading U.S. utilities are on track to meet 10 percent of their power needs with solar).” Most of FPL’s renewable generation comes from landfill gas and wood waste.

Browning adds that Florida has no renewable portfolio generation standard. FPL, he says, “has crushed every effort to establish one. Third-party power purchase agreements, the most popular way of financing rooftop solar in the country, are not allowed in Florida—and every effort to change that has been fought tooth and nail by FP&L.”

On the basis of that record, said Browning, “it is fair to conclude that NextEra is a renewable leader—but only when it is developing projects in other utility service territories…. When it comes to FP&L, the company hasn’t delivered significant renewables itself and has worked to quash customers’ ability to do so on their own.”

Fuel Fights in Hawaii

HECO’s own record of developing renewable energy in a state with a warm climate, lots of sun, and solid hydro and geothermal potential has also come under fire, both from state regulators and from renewable energy interest groups (see sidebar). The Hawaiian utilities have seen substantial growth in solar photovoltaic (PV) technology, but that remains a small component in the state’s generation mix.

| Has HECO Stifled Geothermal Energy?Hawaiian energy consultant and political activist Mililani Trask, who has advised bidders into Hawaiian Electric Co.’s (HECO’s) request for proposals (RFP) for geothermal projects, takes a dim view of the company’s professed commitment to renewable energy. “I have witnessed firsthand how, for the last two years, HECO has sent geothermal bidders on a very expensive ride in one direction while it was quietly pursuing a journey in a different direction,” she says.

HECO laid out a plan in 2011 to get bids for up to 50 MW in geothermal projects, with bids due in mid-2013. Six bidders applied, according to the Associated Press. But the utility, Trask said, adopted a “slow drip” schedule that slipped from 2013 to 2014. “We ended 2014 with no award made for the development of additional geothermal energy to relieve Hawaii residents of the burden of the highest electric rates in the nation. More recently, the company has abandoned the RFP process for a Best and Final Offer and promises a decision by mid-February 2015. Lucy was kinder to Charlie Brown than HECO has been to its bidders.” Hawaii’s only geothermal generating station is Ormat’s Puna Geothermal Venture on the Big Island, with 38 MW of firm capacity. HECO’s Hawaii Electric Light Co. has picked Ormat for an additional 25 MW of geothermal for the Big Island (Hawai’i). The next step, according to a utility press release, is “contract negotiations with Ormat, with an agreement to be submitted to the Public Utilities Commission for approval.” Trask says that Hawaii should end HECO’s monopoly status, subject the NextEra merger to detailed scrutiny, and develop a timeline for terminating HECO’s fossil-fueled generation. |

Hawaii is unique. Its utilities constitute a form of distributed generation, although one that HECO hopes to change. HECO serves Oahu (the biggest load, with about 150,000 customers) and owns Hawaii Electric Light Co. (with 80,000 customers on Hawaii Island) and Maui Electric Co. (with 70,000 customers on Maui, Molokai, and Lanai). These grids on separate islands are not interconnected, meaning they can’t call on each other—or on utilities elsewhere—to realize efficiencies and balance load.

Hawaii’s only other electric utility is the Kauai Electric Cooperative, with 32,000 customers, which also is dependent on oil-fired generation (Figure 1). The cooperative has been aggressively installing hydro and solar generation and plans to reduce its fossil fuel dependency to 40% this year.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) notes that “Hawaii imports almost all of its energy fuels, and a disproportionate share of Hawaii’s electricity comes from oil-fired generators, which is a large part of why Hawaii’s electricity prices are the highest in the United States.”

The high electricity prices, notes the EIA, make solar and wind attractive, particularly as the cost of renewables declines (Figure 2). “These factors have led to growing wind and solar generation on both the utility scale and in smaller distributed applications—particularly customer-sited rooftop solar PV,” says the Department of Energy’s statistical arm. EIA data show that “9,200 net-metered PV systems were added in 2014 through October, bringing the total number of customers with net-metered PV to around 48,000. On Oahu, where most of the state’s population resides, roughly 12% of customers have rooftop solar, compared to an estimated U.S. average of 0.5%, according to the Solar Electric Power Association.”

There’s the problem. HECO has slowed approvals of new net-metering interconnections, as rooftop PV capacity is reaching 120% of the circuit’s daytime minimum load. Says EIA, “once that threshold is passed, an interconnection study may be required before the new PV system can be approved, which has resulted in a backlog of PV applications.”

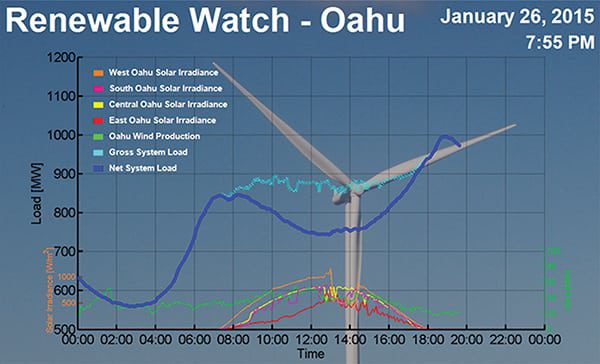

Green technology reporter Jeff St. John observes that Oahu is experiencing the same duck-shaped supply and demand curve seen in California. In Hawaii, HECO calls it the “Nessie curve—caused when midday solar exceeds demand, then drops off to leave the utility with steep ramps in demand to match with limited resources” (Figure 3).

|

| 3. Nessie. This chart shows the blue “Nessie” curve of net system load, as bent by mid-day solar generation on the island of Oahu. Source: Hawaiian Electric/EIA |

HECO’s delay in approving new PV interconnections prompted the Hawaii Public Utilities Commission (PUC), which has a long and contentious relationship with HECO, to demand changes in how the company deals with distributed energy generation. In response, HECO in late January filed a plan with the regulators to increase the allowable PV penetration threshold to 250% of the circuit’s daytime minimum load. EIA notes that “this change would also be accompanied by a decrease in the amount received by new net-metered customers for the excess electricity they send back to the grid. Instead of receiving the full retail rate (about $.30/kWh for Oahu residential customers in January 2015), customers would receive something closer to Hawaiian Electric’s cost of avoided generation, which largely reflects the cost of purchased fuel.”

Distributed Renewables or Transmission?

Winning that change HECO has proposed for its solar PV program may be the key to the economics of the NextEra deal, according to Forbes magazine contributor William Pentland. “The return (or lack thereof) on this $6 billion investment will likely depend on future development trends of distributed generation in Hawaii,” he says.

Pentland explains that HECO wants to invest heavily in transmission to interconnect the three island systems, starting with a $600 million undersea cable between Oahu and Maui, capable of 200 MW of bidirectional transmission. He points out that a key to the transmission project is that it is not subject to the jurisdiction of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, because it is entirely within the isolated state of Hawaii, greatly simplifying the regulatory path for the project.

Pentland says, “The only way to pay for that undersea cable is to use it. The project becomes far more cost effective as the amount of energy it transmits increases. In other words, the interconnection only pencils for investors (and customers) if it moves a whole lot of electricity for years and years.” He adds, “Every dollar customers spend on rooftop solar panels is a dollar they don’t spend buying power from the centralized grid.” In the merger agreement with NextEra, Pentland notes, “NextEra has significant influence on HECO’s regulatory agenda. Indeed, the agreement states that HECO must receive written consent from NextEra prior to settling ‘any rate case or other material proceeding that would impact the ratemaking mechanisms currently in effect.’”

HECO’s proposal is likely to upset consumers and renewable energy advocates. That could translate into opposition from state politicians and regulators. In his “state-of-the-state” address in late January, new Democratic Gov. David Ige noted the NextEra deal and said he has charged Randy Iwase, his nominee to chair the state utilities commission, “to be actively involved” in the merger negotiations. Iwase has said public input will play a big role in the review of the buyout. Even before the NextEra bid, Iwase said that the commission has been skeptical of HECO’s commitment to renewables. Ige also said he “will be restructuring and staffing the PUC to give it the expertise and resources needed to deal with its due diligence. I will also be assigning a special counsel to protect the public’s interest for the short and long term.”

Hawaiian Rep. Chris Lee, chairman of Hawaii’s House Energy and Environmental Protection Committee, wants conditions and benchmarks for cost reduction and renewable goals in exchange for the merger. He also wants the state to study a takeover of the investor-owned utility, turning it into a public power agency, with the Kauai cooperative as a model.

In many respects, Hawaii is a microcosm of the tensions between traditional fossil-fueled generation and transmission systems and more distributed renewable types of generation. For its part, NextEra Energy has heretofore largely dealt with distributed renewables and utility-scale generation on different terms. Whether it can resolve the tension between the two models in Hawaii remains to be seen. ■

— Kennedy Maize is a POWER contributing editor.