Even though it may dominate forecasts, natural gas–fired generation faces a troubled expansion in the U.S., according to experts from a variety of stake-holding entities—including an industry group, a utility, a generator, and a pipeline company.

Challenges that have few solutions—from price volatility, to gas transport concerns, to rule uncertainty—may upend the nation’s dependence on natural gas, they cautioned.

Gas Price Volatility

The ultimate driver for the nation’s much-talked-about shift to natural gas generation has been low natural gas prices, as Lola Infante, director of generation fuels for industry group Edison Electric Institute, told attendees at the Gas Power 2016 conference in Houston, Texas, on June 8.

If standard heat rates were used to convert natural gas and coal prices to prices for electricity generation, this May marked the seventh consecutive month that natural gas prices at Henry Hub, averaging $15.87/MWh, were less than Appalachian coal prices, which remained relatively stable at $18.40/MWh. Meanwhile, record amounts of natural gas are being used for electricity generation. But looming over the power generation sector that is leaning on natural gas to fuel its future is price volatility, she warned. “If natural gas prices go up, the fuel switching will stop, and if gas prices continue to stay low, then it will continue to go really fast,” she said.

The nation’s build-out of natural gas is also being prompted by grid flexibility needs created by the integration of variable renewables, Infante said. In 2015, she noted, of the 14.5 GW of new capacity added in the U.S., 47% was wind, 35% natural gas, and 14% was solar.

She also noted that power plant retirements—not just coal retirements—were driving new gas plant additions (see POWER‘s June 2016 BIG PICTURE infographic for an analysis of retirements by fuel over the last decade). While environmental rules and economics have forced or will force mass retirements of coal plants, a large swathe of mostly natural gas steam turbine plants are also more than 65 years old—and many are due to retire.

The Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) and PJM Interconnection areas have been hardest hit by coal retirements, yet the retirement trend is still “fluid,” she said, adding, “At any point, things could change, or they could move in a different direction.”

At the same time, a number of “transformation drivers” pose more uncertainties, including public policies (such as for climate change mitigation), financial incentives like tax credits, customer demand, such as for rooftop solar, and new technologies, models, and uses. For example, “[distributed generation] is the hottest topic in D.C. right now,” she said.

Energy storage, too, has come out of the “wishful thinking category” and into the real world, and its growth is projected to be exponential. Additionally, microgrids are multiplying, and utility-ownership models are in flux, she said.

Grave Market Concerns

From the utility perspective, too, the rapid shift to natural gas within an already morphing power landscape has been dizzying. The shale gas fracking revolution that changed the scene only got started in 2008, noted John Kosub, director of CPS Energy’s supply side analytics division. Just five years ago, the San Antonio, Texas–based municipal utility—the nation’s largest—used natural gas to fire 17% of its fleet. Today 43% of its markedly more diverse fleet is gas-fired.

But the transition hasn’t been all rosy, Kosub said, pointing to market concerns that are evolving within the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) region covering most of Texas. ERCOT, which is facing retirements of up to 4.7 GW of coal capacity owing to the Clean Power Plan and regional haze requirements, wants to add 6.2 GW of new gas-fired generation by summer 2018. Adapting to the changing landscape, it is also looking at ancillary services and a future distributed energy resources (DER) framework, he said.

Between 2010 and 2015, the reliability gatekeeper that was confronting a negative reserve margin just three years ago added 2 GW of natural gas, 1.6 GW of coal, 7.1 GW of new wind, and 740 MW of new solar capacity. But adding new capacity has had the effect of lowering market prices on average while “most generators are already challenged in this current market.” Kosub said.

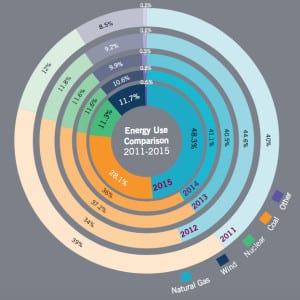

ERCOT’s changing fuel mix. Compared to 2011, when natural gas fueled 40% of power plants on the grid overseen by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, in 2015, nearly half of ERCOT’s grid was fueled by gas. Courtesy: ERCOT

“You wonder about some of the capacity that has been added,” he said. “If it were a rational economic market, you wouldn’t build that until there was indication that supply was tightening and you could return your investment.”

An Insidious Gas Transport Problem

Meanwhile, and perhaps more worryingly, market woes faced by generators are significantly complicating gas transport issues, noted Richard Kruse, vice president for regulatory affairs at Spectra Energy, the company that owns and operates the Algonquin Gas Transmission pipeline. For the last four years, the 1,129-mile pipeline that traverses New England, New York, and New Jersey has run at 100% capacity, Kruse said, and that has meant seasonal supply issues for generators in New England, which is increasingly relying on natural gas for power owing to its market structure.

“Change is coming fast,” he said. Ten years ago, the region banked on natural gas for 12% to 14% of its generation, but now it’s 60%, he noted, attributing it to the rapid phase-out of coal and nuclear capacity. Up to 30% of New England’s generating capacity could be retired by 2020, replaced largely with natural gas–fired power plants.

“That’s great news for the gas industry,” but now, the region crippled by market volatility is suffering supply constraints. These stem from a stark lack of firm pipeline capacity commitments from generators that are struggling to keep plants profitable. “The end result is the markets in New England–and this is our experience pretty much across the nation—are relying on capacity rules and secondary transportation to get the gas to them,” he said. Without firm contracts for pipeline capacity, generators can be left with no means to receive gas on days when there is high demand.

This has resulted in sudden scarcity and price surges, Kruse said. For example, compared to the MISO, which sees winter peak wholesale power prices of $29.31/MWh, generators within the ISO New England region see skyrocketing prices of about $76.64/MWh owing to system constraints as local distribution companies pull back capacity.

To mitigate these issues, Spectra is developing Access Northeast, a project that is designed to upgrade the existing Algonquin Gas Transmission system and add regional liquefied natural gas assets in New England. The approach seeks to avoid overbuilding new pipeline infrastructure while still delivering up to 925,000 dekatherms per day beginning in late 2018.

Kruse also outlined a number of optimal services that could benefit the power sector, including a “no-notice” gas transportation service with a quick-start option, and reserved firm capacity that can be used on a “no-notice” basis any time during a gas day.

The Pains of Building New Gas Generation

Finally, building new gas power plants isn’t easy, stressed Peter Furniss, CEO of Footprint Power, a company that is putting up a 674-MW gas plant on the site of the former coal- and oil–fired power plant in Salem, Mass. The $1 billion plant, the first built in Massachusetts in more than 13 years, is slated to come online in June 2017—nearly a year later than planned, largely due to permitting hurdles and opposition.

To keep the process going, New Jersey–based Footprint Power ultimately struck a deal in 2014 with environmental group Conservation Law Foundation—an organization with which it had been in dialogue since the project was conceived, Furniss revealed—to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the new Salem Harbor facility annually over its 40-year lifespan to meet state climate change mandates.

“The development process is an unending process,” Furniss said. “It is something that requires a great deal of discipline and requires that you keep going back to your repository of data to keep the process going.”

One way that his team minimized delays was to share Footprint’s goals early in the process with its broader stakeholder group. Communication was integral in reducing risks because it minimized local opposition and it eliminated barriers to assistance from interested parties, he said. It also served well to crystallize project elements early in the process to avoid costly changes later. “Projects with reduced risks are easier to finance at all stages of development,” he noted.

But larger, more under-addressed issues plague the industry, many arising from system complications, Furniss cautioned. “As an industry, we have legitimate gripes about the way our system is run. As a developer and an independent power producer [IPP], I’ve been battling three aspects of the rules: That they are unclear, inconsistent, and unpredictable,” he said. “It doesn’t matter which [regional transmission operator] you are in, I think we all struggle with this.”

At the heart of the issue, he said, is that the industry views itself in “silos”—IPPs versus utilities, for example—and that makes it hard to “attack the rules with any legitimacy.”

“It makes absolutely no sense for everyone to be living under uncertainty,” he said.

—Sonal Patel, associate editor (@POWERmagazine, @sonalcpatel)