On January 30, as part of a flurry of new policies, President Donald Trump signed the “Presidential Executive Order on Reducing Regulation and Controlling Regulatory Costs.” The stated purpose of this order is to reduce the federal regulatory burden on the U.S. economy. The outcome, at least in the short term, is likely to be the exact opposite.

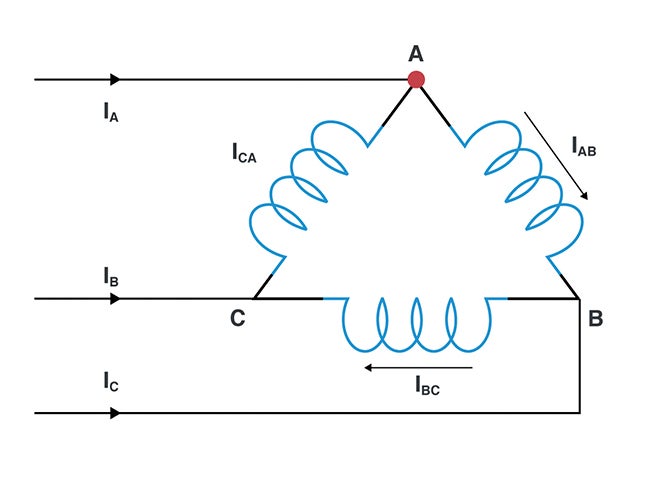

The order states, “Unless prohibited by law, whenever an executive department or agency… publicly proposes for notice and comment or otherwise promulgates a new regulation, it shall identify at least two existing regulations to be repealed.” In other words, to issue any new rule, no matter what it may address, the federal agency proposing it must eliminate two others. The net incremental cost of new regulations must also be zero, offset by eliminating “at least” two existing regulations.

To anyone with any familiarity with the federal rulemaking process, Trump’s order is an astonishingly ham-fisted approach more suited to an internet comment section than the serious business of running the federal government. Let’s accept for the purpose of this column that the U.S. economy is overregulated and that reducing that burden is a worthy goal. But the burden of those regulations is not necessarily correlated with their number.

Most federal regulations are actually narrow in scope and have limited to negligible economic impact. A few, like the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards (MATS)—to name just one with an impact on the power sector—are very broad in scope and have very large economic impacts. Eliminating a few trivial regulations to enact a broad one isn’t going to do anything to reduce regulatory burdens.

It’s unclear what, exactly, qualifies as “repeal” of an existing regulation. Suppose an agency wants to scale back a current regulation but not repeal it because it has burdensome elements but also beneficial ones. Under the law, this requires a new rulemaking process. But is this less burdensome rule a “new” regulation, a “repealed” regulation, or neither?

Impact Arguments

The next problem is that calculating the economic impact of a proposed regulation is far from an exact science, and there is a great deal of disagreement on methodologies and assumptions. Congress usually provides guidance on what factors may and may not be considered, but there is always some agency discretion and often a great deal of it.

Typically when a new regulation is proposed, estimated costs are entirely offset by projected benefits. Consider the debate in the run-up to the Obama administration’s update to the National Ambient Air Quality Standards in 2015. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated $40 billion in health benefits against $15 billion in compliance costs. By the EPA’s math, this regulation had a net positive impact on the economy. The National Association of Manufacturers, however, argued that it would have $46 billion in annual costs and negligible health benefits, making it a net negative.

Then there’s the issue that benefits and impacts don’t fall equally. Costs often fall most heavily on businesses while benefits accrue to consumers, and such benefits are often difficult to quantify when it comes to issues like public safety.

It’s not at all clear how the two-for-one cost calculus would work, and the order just punts the issue to the Office of Management and Budget for “guidance.” Estimates of economic impacts are made when regulations are promulgated, but those estimates are not updated. If an agency proposes eliminating a pair of regulations that have been in force for 20 or 30 years, how is the net cost to be calculated?

Then we come to the fact that the executive branch cannot necessarily just eliminate regulations on its own initiative. The executive, after all, doesn’t make the law, Congress does. The authority to issue federal regulations stems from some enabling legislation, which often does not give federal agencies a lot of discretion about issuing them or sometimes any discretion at all.

One lament I’ve heard from lawyers who work for the EPA is that people don’t realize the EPA very often does not have the option to refrain from issuing a regulation. The Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, for example, mandate that the EPA regulate various pollutants, and these mandates have been given extra force by decades of legal precedent. Executive order or not, Trump’s EPA can’t simply throw out these regulations.

Litigation Bonanza

Add all this up, and what you get is one of the most common complaints about federal regulation: uncertainty. The order creates enormous uncertainty about the future regulatory environment and its impacts, and one thing uncertainty guarantees is litigation. The federal regulatory process is already an enormous source of litigation, and the order ensures the situation is about to get a whole lot worse.

Changes to published regulations, including repeal, require a rulemaking process. This means that instead of one such process, any new rules will apparently now require three of them. Rest assured that special interest groups will be suing not just over the new regulation but also over the two (or more) being eliminated. Finally, leaving aside all these problems, there’s a fair argument that the order itself may be illegal, because it injects an additional balancing factor into the federal rulemaking process over and above what Congress has already specified.

President Trump could have taken a more rational approach and ordered a top-to-bottom review of the federal regulatory regime to identify the most burdensome regulations and those most ripe for rollback. That would not, however, have fit into the broad-brush, 140-character limitation of Twitter through which he appears to prefer promulgating his policy initiatives. ■