Domestic competition is coming to the U.S. market for enriched uranium reactor fuel, with one competitor to what had been the only American firm making separative work units (SWUs) expanding its capacity and two new projects waiting in the wings.

In the most recent development, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has given a General Electric-Hitachi subsidiary, Global Laser Enrichment (GLE), a license to roll out an advanced enrichment technology at a plant planned for an existing GE nuclear fuel fabrication plant in North Carolina. The SILEX (Separation of Isotopes by Laser Excitation) technology uses lasers to knock out the needed uranium-235 atoms from a gaseous stream of natural uranium, consisting mostly of U-238. It is based on work done by the U.S. Department of Energy in the 1980s when the U.S. government owned the enrichment enterprise, later spun off to USEC.

The NRC license allows the GE venture to enrich uranium to no higher than 8%. Some groups concerned about proliferation of atomic weapons have opposed development of the laser technology as an easier path to bomb-grade uranium, which requires enrichment to at least 90% U-235 by weight.

Former European competitors have been slowed in the U.S. market, the largest in the world for enriched uranium fuel, by U.S. government trade policies, including a Commerce Department ruling that European competitors Urenco and Areva were “dumping” SWUs (a measure of the work required for an enrichment process) on the U.S. market at below cost. So competitors for the Maryland-based monopoly USEC have brought their game to this country and are positioned to make a big impression on the market. The result is likely to mean sustained low fuel prices for owners and operators of atomic generating plants.

USEC, the dominant U.S. producer, has been trying for years to replace its elderly, inefficient gaseous diffusion plant in Paducah, Ky., which began operating in 1952 as part of the U.S. atomic weapons program, with a new centrifuge plant in Portsmouth, Ohio—though one based on failed DOE centrifuge technology from the 1980s. The project, which depends on U.S. government financing, has moved in fits and starts. Most recently, Congress agreed to keep $350 million in DOE funds flowing to the program, under the rubric of research and development, after the government declined to award a $2 billion loan to the project.

Much of the enriched fuel coming to the U.S. in the past decade has been the output from a U.S.-Russian program to turn excess weapons-grade uranium to reactor fuel as Russia has scrapped much of it its atomic bomb arsenal in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union. Since 1993, USEC has dowgraded (“impoverished” according to some wags) some 450 metric tons of Russian uranium into reactor fuel, meeting about 10% of U.S. demand for SWUs. That “megatons to megawatts” program ends in 2013.

The U.S. market for enriched reactor fuel is about 12.7 million SWU annually, according to the World Nuclear Association, with USEC currently supplying about 8 million SWU, while piling up big losses. USEC reported that its 2011 losses totaled some $541 million ($4.80/share) on revenues of $1.7 billion.

Today, USEC’s chief domestic competitor is Urenco’s gas centrifuge plant in Eunice, N.M., with a current capacity of 2 million SWU. In August, Urenco announced that it has begun supplying a second production line of upgraded centrifuges with uranium hexafluoride feed. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has licensed the plant for up to about 6 million SWU annually.

Waiting in the wings is Areva, which is looking for additional investors in its planned Eagle Rock centrifuge enrichment project in the eastern Idaho desert near DOE’s Idaho National Engineering Laboratory. Areva has a $2 billion conditional loan for Eagle Rock from DOE, but put the project on hold in December 2011 as the French government-owned company faced serious economic obstacles in Europe. Areva hopes to start construction of the plant, with a planned capacity of 3 million SWU, in 2013 or 2014, and says it has commitments from customers for 70% of the plant’s output.

Areva, which is facing multiple marketplace difficulties including two nuclear plant construction projects that are going badly in addition to a soft nuclear fuel market, has been scaling back major portions of its fuel business. The company announced in October that it will delay start of a billion-dollar uranium mine in Namibia until business conditions have improved. The plant, using a new heap leaching chemical extraction technology, was about 80% complete, but Areva said uranium prices have to be at least $74/pound for the mine to make a profit. Recent uranium spot market prices have been in the $45/pound range, down from $70/pound just before the March 2011 Fukushima disaster.

If USEC can get its Portsmouth enrichment project off the ground, the company is likely to shut down its loss-generating gaseous diffusion plant and move production to the new plant. But if it is unable to pull off the Ohio project, USEC may die, according to an analysis by Stanford University economist Geoffrey Rothwell. “The U.S. government has been subsidizing the USEC since its privatization,” he wrote. “It is unlikely that USEC will survive without a continuous infusion of federal capital until the [advanced centrifuge project] is finished.”

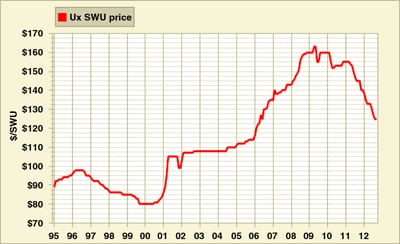

Given the slowdown in both U.S. and world nuclear markets, SWU prices have been falling steadily since the Great Recession began biting in 2009; the descent accelerated following the Fukushima disaster in Japan. Figure 1 from UxC shows the price trend:

1. SWU prices are dropping. Source: UxC

Given current market conditions, it doesn’t look like that picture is going to be much different in the next few years.

—Kennedy Maize is MANAGING POWER’s executive editor. Sonal Patel, senior writer at POWER magazine, contributed to this article.