Six draft policy statements unveiled by the UK’s Energy and Climate Change Secretary Ed Miliband on Monday map out an energy future that focuses on a “trinity” of fuels: nuclear, renewables, and “clean” fossil fuels. Miliband also identified 10 suitable sites for the nation’s next generation of nuclear plants and a new policy for the transition to clean coal.

“New infrastructure is being provided for the coming years, with 20 GW under construction or consented, more than that which will close by 2018,” Miliband told members of parliament (MPs).

“But to meet our low carbon energy challenge, and due to the intermittency of wind, we will need significantly more generating capacity in the longer term. Over the next 15 years to 2025, one third of that larger future generating capacity must be consented and built,” he warned.

The six National Policy Statements (NPS) include an overarching one, and one each for fossil fuels, nuclear, renewables, transmission networks, and oil and gas pipelines. Miliband said that “reforms” outlined in the statements would be “faster and fairer for everyone involved.” For example, it moved to speed up decisions on power generation proposals of larger than 50 MW (100 MW for offshore wind) from two years to as little as one year.

New Nuclear Is Necessary

Miliband said nuclear power was essential to combat climate change and ensure energy security in the decades ahead, calling it a “proven, reliable source of low carbon energy.” He identified 10 of 11 sites nominated by industry in March as potentially suitable for new nuclear deployment by the end of 2025: Bradwell, Braystones, Hartlepool, Heysham, Hinkley Point, Kirksanton, Oldbury, Sellafield, Sizewell, and Wylfa.

Dungeness was nominated but not listed, because the government did not consider that potential environmental impacts at this site could be mitigated, the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) said in a statement. “The Government also has concerns about coastal erosion and associated flood risk at that nominated site.”

Miliband told MPs that the first new power plant should be operational by 2018, and by 2025, at a cost of £5 billion each, new plants could generate a quarter of the country’s energy—compared to 13% now.

He also said that the government was “satisfied on the basis of the science and international experience” about its plans to store radioactive waste from the new nuclear power plants in a deep underground facility that could cost up to £18 billion to build. Additionally, he signaled that the government had opened consultation on the proposed regulatory justification for the two different reactor designs under consideration: Westinghouse’s AP1000 and AREVA’s EPR.

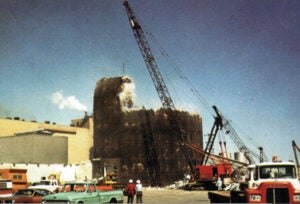

Counting on Clean Coal

Along with the NPS, the UK government on Monday unveiled a framework for the development of clean coal. That document establishes with immediate effect that new coal plants would not be permitted in the UK—unless they could demonstrate the full carbon capture and storage (CCS) chain (capture, transport, and storage) from the outset on at least 300 MW net of their total output.

The government has been looking to fund development of CCS in the nation, launching a competition in 2007 with the final goal to demonstrate a full CCS chain by 2014. All contenders must agree to use postcombustion technology to capture 90% of greenhouse gases from a coal plant. It has been widely reported, though not formally disclosed, that the winning bidder could gain £1 billion in public funding.

But the deadline for the competition—which was supposed to take a year—has been repeatedly pushed back. On Monday, the competition suffered yet another setback as a consortium of Denmark’s DONG Energy, Germany’s RWE, and UK company Peel Energy confirmed it was no longer participating in the contest.

“The consortium made its decision to withdraw from the competition for funding for a 400-megawatt CCS demonstration project because the competition timetable is not compatible with the partner companies’ respective coal development plans,” it said in a statement.

This consortium isn’t the first to withdraw: BP PLC pulled out of the competition in 2007 because of timeline uncertainties. Last month, Germany’s E.ON delayed plans to build a new facility at Kingsnorth because of economic concerns. That company remains in the competition, however, as does ScottishPower, an Iberdrola company, which is contending for funding of its Longannet coal-fired power plant in Scotland.

The DECC confirmed on Monday that it expects demonstration plants could retrofit CCS to their full capacity by 2025, with the CCS incentive able to provide financial support for their retrofit.

“A rolling review process, which is planned to report by 2018, will consider the case for new regulatory and financial measures to further drive the move to clean coal,” it said. “In the event that CCS is evidently not going to become a viable technology option, an appropriate regulatory approach for managing emissions from coal power stations will be needed.”

E.ON and ScottishPower were expected to remain contenders for the next stage of the competition—and all contracts for the detailed design stage would be concluded early next year, it said.

Sources: DECC, POWERnews