Courtesy: PetroChina

China has a lot of shale gas. To the tune of 1,275 Tcf of technically recoverable shale reserves, by some estimates. But today it is all still sitting in the ground. If that potential is tapped in any significant way, it will have a huge impact on global gas balances, with implications for liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets, economic competitiveness, and geopolitical clout. But a lot of obstacles must be removed before the promise of Chinese shale gas can be realized. A couple of weeks ago I spoke at the Global Unconventional Gas Summit, held in Beijing. After listening to two days of presentations on the issues, I came away with the view that while some of these barriers are inherent in the Chinese system, probably the biggest barrier is a general misunderstanding of why shale gas developed the way it did in the U.S. in the first place.

The 3rd Annual Unconventional Gas Summit was hosted by Gas Technology Institute and China Energy Research Society (CERS). It is an outgrowth of initiatives between the U.S. and China for the transfer of shale technologies, and so there were a lot of speakers from government agencies like China’s National Energy Agency, Ministry of Land and Resources, and Ministry of Science and Technology. And there were also many presentations from China’s “Big 3” national oil companies (PetroChina, Sinopec, and CNOOC) and more service providers than you could count.

These folks have some ambitious objectives. The Chinese have plans to get from a standing stop—a few demonstration wells today—to 630 MMcf/d by 2015. It is hard to argue that the Chinese can’t make it happen. Give the Chinese a five-year plan, and the resources are going to be there. And some highly qualified experts from the U.S. side are working hard to get the technology transfer process up to speed.

But there are some big obstacles ahead, and most are not directly tied to the resource allocation and technology transfer processes that were discussed at the conference. I split the obstacles into two groups: those that stem from the Chinese ways of doing business, and misunderstandings about how and why shale happened in the U.S.

The Chinese Way of Doing Business in the Oil and Gas Sector

The Chinese economy may be vastly more open than it was 25 years ago, but in sectors of the economy like oil and gas, it is still a very top-down structure. The industry is made up of the Big 3: PetroChina (a subsidiary of China National Petroleum Corp.), Sinopec (China Petroleum & Chemical Group), and China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). PetroChina and Sinopec are two of the 10 largest oil companies in the world. All three of these companies are majority owned by the Chinese government.

Overarching goals for these companies, and the rest of the economy for that matter, are set in five-year plans. China is in the middle of its 12th five-year plan (2011–2015) with goals set by China’s National Energy Administration, Ministry of Land and Resources, etc. Those are the organizations that decided that China should be doing 630 Mcf/d of shale gas by 2015.

Theoretically, the shale gas goal can be met either by one or more of the three state companies, or by foreign companies doing business in China. In practice, it will most likely be the Big 3. That is because the procedures for foreign companies are ill-defined at best and do little to assure companies that they will actually be able to monetize their successes.

Here’s one example to make the point. What we would call a minerals lease (the right to explore for and then capture hydrocarbons) is instead in China structured as a license to explore. And then if hydrocarbons are found, it can be converted to a license to produce. But no guarantees. We are not talking property rights here. You’ve got to be a trusting soul to lay out the money up front with no certainty of being able to monetize your success. Similar murky rules (if any) exist for all aspects of the shale development process, from the availability of water to access to pipelines. Not to mention that the Big 3 already hold licenses for most of the good shale prospects. So until the legal framework and rules of the road get shorn up, that makes the Big 3 the only viable candidates for shale development.

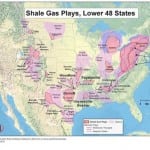

That gets us to the big company problem. We all know that it was not the U.S. multinational majors that launched the shale revolution. It was the independents who went to school on George Mitchell’s years of trial-and-error in the Barnett, and adapted those technologies in other basins. This point was not lost on several of the Chinese speakers, with many referring to the entrepreneurial spirit and risk-taking culture of independents as the reason for their dominance of early shale development.

But was that really the reason why the independents led the charge? It is not like the majors don’t take big risks. They put billions of dollars on the line for offshore platforms, and in third-world countries, where there is no guarantee of success. And they pour billions into research to develop the next exploration and production technologies, with no guarantee that the research dollars will pay off. Why then did these organizations not see the potential for shale and then make it happen?

Since there will apparently be no independent sector to launch Chinese shale, we need to look deep into this question to understand the implications for Chinese shale development.

Why Did U.S. Shale Happen the Way It Did?

What was the advantage that the independents had over the majors? It certainly was not resources. Or access to technologies. After all, hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling have been around for decades. And it was not the discovery of a cheap way of drilling for hydrocarbons. Horizontal wells with multi-stage fracs are expensive wells—not cheap. Here’s my three-part theory for why it happened the way it did.

First, development of a new shale play is as much art as it is science. What works for one shale does not work in the next one. And there is no Book of Shale to consult. The independents were willing to hack around with different processes, formulas, and techniques until they came up with things that worked. If you don’t like the word hack, then call it “crack the code.” Regardless of what you call it, it is a trial-and-error process where there are far more errors than successes. You hear a lot about the successes. You don’t hear so much about those who were not successful. But failures happened. It’s that thing we call risk.

In those early days, minerals leases could be had at attractive rates, which meant that there was a whole lot of money on the table if the code could be cracked. That kind of motivation works really well for scrappy independents going for the big score.

Second, the independents discovered (quite possibly by accident) that horizontal drilling and fracking had a huge benefit beyond simply being able to produce from previously uneconomic formations. Breaking open the rock and getting those fissures connected to a very long lateral meant that the wells were big—really big. Three to 10 times the initial production rate of conventional wells. Yes, they had a dramatic first-year decline rate, but they started off so big that the wells would pay out very quickly (at least back in the good ole days of $4.00 prices)—before the production rate dropped too much. You could then use the up-front cash return from that well to go drill another. This way of producing gas is quite different from the “drill now and produce for years” model that was used in the past by the majors. This is what has been called the “factory model” because the producer is always drilling the next well to make up for the production declines in previous wells.

And this is the key. The steady addition of new, big-volume wells drives the per unit cost of shale gas down. That’s the big driver of shale economics—low per unit cost of production due to an initial surge of volume in the first couple of years of a well’s life.

Third, the independents gravitated to plays where the factory model worked best—and that is where the geology was relatively consistent and understandable. For the factory model to work, the producer needs repeatability. Drilling wells in several of the big shale basins turned out to be repeatable simply because the geology was compatible with horizontal drilling. And again, enough independents were willing to take a trial-and-error approach until they figured out the good ones.

All of this trial-and-error, hacking around stuff is not a good fit with the processes inside most big companies. There the modus operandi is about careful planning and predictable outcomes. Yes big E&P companies deal with huge risks and astronomical investments where a dry hole is always a real possibility. But you plan for that possibility. You risk-adjust your returns. You don’t go hacking around well-after-well trying to figure out something that will work with a particular rock. That’s just not in the culture. It is much safer to have the independents go do all the hacking around, and then go buy one or two that have broken the code in one of the big plays.

That gets us back to China. I have no personal familiarity with the cultures of the Big 3 Chinese oil and gas companies. But I do have some experience with a big producer here in the U.S.—thanks to a 20-year career with Texaco. And based on that experience, I’ll submit to you that the early shale development process is a poor fit for a big company culture. In any company, whether it is American or Chinese, success in early stage shale is not about process. It is about a willingness to fail over and over again until you get it right. It is not about producing gas from shale. It is about making money. The know-how to produce shale is the means to that end, not the end in itself.

I am anything but a Chinese oil and gas expert, so I could be wrong about all of the implications for Chinese shale. But I’ll bet that the odds of a Chinese shale success story in a meaningful timeframe would be much more likely if they could figure out a way to get the Chinese version of an independent oil and gas sector working in their country.

Surprise, Surprise, Surprise

One final random thought. There were a lot of speakers at the conference who talked about how much of a surprise it was to the U.S. when the shale phenomenon happened. Some of their evidence included the huge changes in reserve estimates between 2007 and 2010, the fact that LNG import terminals were still being built late in the decade, and how EIA projections of shale production jumped dramatically over the past few years. I’ll submit to you that the people who were drilling for shales back in the 2007–09 timeframe were not surprised at all. And they were not keeping their successes a secret. It is just that most of the world was not listening, or just could not believe that the business of producing oil and gas was undergoing a fundamental shift. But it was. Let that be a lesson. Sometimes hype is hype. Sometimes hype is the real thing.

—Rusty Braziel is president & principal energy markets consultant for RBN Energy. A version of this article was originally published on the RBN Energy Blog.