Nigeria’s government joined with Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corp. (Rosatom) last year with a goal to develop the country’s first nuclear power plant, a plan that both sides confirmed and talked about in May at the 2018 AtomExpo in Sochi, Russia. The agreement is designed to start Nigeria on a path for nuclear power within the next few months. It’s something discussed by Nigerian governmental leaders for years though denounced by environmental and human rights groups. Those groups say the country cannot afford the costs associated with building a nuclear plant, and they also have concerns about radioactive waste. The groups instead support the government’s investments in renewable energy, including solar and hydropower.

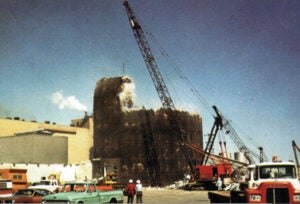

Nigeria and Russia signed an inter-governmental agreement on nuclear science at the 2016 AtomExpo, which paved the way for the October 2017 agreement between Rosatom and Nigeria to build and operate a nuclear power plant and research center in Nigeria (Figure 1). The latter agreement was finally confirmed by Viktor Polikarpov, Rosatom’s vice president for sub-Saharan Africa, and Simon Pesco Mallam, the chairman and CEO of the Nigeria Atomic Energy Commission, at the Sochi conference in May. Mallam told Britain’s The Guardian newspaper: “We have a [nuclear] roadmap and that is by the mid 2020s. We hope we can get a commercial plant and add three more in five to 10 years.” Mallam has said government studies showed nuclear plants could be built in Geregu in the Ajaokuta area of Kogi state, and Itu in Akwa Ibom state. He also told the newspaper, “We have a good agreement with Russia, but we have not signed any contractual agreements yet. We have signed operational agreements, project development agreements, but not any commercial contractual agreements.”

Polikarpov, discussing the economics of nuclear plants at the conference, said the cost of uranium as nuclear fuel is comparatively low compared to coal and natural gas, and while the cost to build a nuclear plant is high, operational costs are low, particularly considering the 60-to-80-year lifespan of a nuclear facility. Whether that would sway nuclear opponents remains to be seen; two plants proposed in 2015 by the administration of then-President Goodluck Jonathan, in the locations noted by Mallam, met with strong opposition, due to financial and environmental concerns. Tommy E. Okon, president of Akwa Ibom, has repeatedly said, “We reject anything that is not in the interest of our state and our people.” In 2015, the Nigeria Atomic Energy Commission disclosed that five Nigerian universities were hosting centers for the study, research, and development of nuclear projects.

The push for developing more energy sources comes as Nigerian officials acknowledge about half the country’s 198 million people have no access to electricity, and the country’s population is expected to more than double in the next 30 years. Babatunde Fashola, the country’s power minister, in May told Reuters the country needs more than 10 times its current generation output to guarantee an adequate supply of power for its population. There also is an ongoing effort for more renewable power in Nigeria, which has a goal of increasing access to electricity to 75% of its people in the next two years, and to 90% of its population by 2030. Fashola earlier this year told a London audience that the country wants to produce 30% of its power from renewable sources by 2030.

Though the country is often cited as among the world’s poorest, with about a third of the population living in “extreme” poverty according to the World Bank, it also has a growing economy, rebounding from a downturn in 2016. FocusEconomics, a group of the world’s leading economists, forecasts a 2.6% increase in gross domestic product (GDP) this year, and a 3% rise in GDP in 2019. The country’s economy is mostly dependent on the wealth generated from its production of crude oil. Nigeria leads Africa in oil production with about 2 million barrels per day, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, and ranks among the top 15 nations globally in oil output.

It has money to invest in energy projects; government data shows more than $20 billion was invested in solar power projects in the past year. In addition, a $350 million World Bank loan will be used to build 10,000 solar-powered mini-grids by 2023 in rural areas, bringing power to hospitals, schools, and households, according to Damilola Ogunbiyi, managing director of the Rural Electrification Agency. Investments in hydropower include the $5.79 billion Mambilla Power Station. Most of that 3,050-MW project in central Nigeria, scheduled to be online in 2024, has been financed by China-backed lenders.

Fashola said Nigeria has about 7,000 MW of power generation capacity, but only about 4,000 MW actually enters the grid, due to infrastructure and other problems, including water shortages that have curtailed its generation of hydropower. Officials have said there is abundant natural gas available in the country for power projects, but more pipeline infrastructure is needed to get the gas where it needs to go (see “Pipeline Project Prompts Plan for Nigeria Power Plants” in the February 2018 issue of POWER).

—Darrell Proctor is a POWER associate editor.