Predicting the U.S. power industry’s 2008 performance requires understanding how utilities and other plant developers respond to risk and uncertainty. Three years ago, mercury controls had the undivided attention of every coal plant operator. Today, the imminent arrival of carbon controls has caused a tectonic shift in the industry. In years past, builders of new power plants focused on getting grandfathered out of new regulations. Today, developers are canceling plants before the climate change debate in Congress has ended, already assuming the results will be bad for them.

Even the mere anticipation of carbon controls, and the sea change they will bring to the U.S. economy, has created strange bedfellows and stranger enemies. Environmental groups are now embracing nuclear power because they perceive it to be the lesser of two evils—after coal. Proposed carbon cap-and-trade regulations have executives of nuclear and wind power utilities vilifying their counterparts at coal-based utilities, who are asking for “need” allowances to ease the transition.

Thirty years ago, America’s major utilities faced common challenges arm-in-arm. That time has passed.

PURPA’s legacy

For example, 30 years ago utilities uniformly opposed passage of the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) as part of the National Energy Act. The Iranian revolution of 1978 began a period during which world oil prices doubled and some industry wags predicted $100/bbl oil. PURPA forced utilities to diversify their generation resources and to purchase power from privately owned “qualified facilities.” The transition was difficult for industrial plant owners and utilities alike for several years, but market forces prevailed. Today, non-utility generation provides 35% of America’s supply, and more than 44 GW of nuclear capacity is owned by independent power producers (IPPs).

PURPA also was instrumental in creating the U.S. renewable generation market. For example, PURPA-inspired revisions to interconnection rules, long-term power purchase agreements, and tax credits made early solar thermal projects economic in the 1980s. Some credit PURPA with opening the door for 12,000 MW of nonhydro renewable capacity.

As the IPP market matured, natural gas–fired combined-cycle projects became the rage for their high efficiency, ease of permitting, small footprint, and short construction time. Gas-fired plants generating over 150 GW were built by 2006, when skyrocketing gas prices demoted so many plants designed for baseload operation to peaking service. Some were even mothballed.

Which way forward?

PURPA was no longer needed once the U.S. generation market had become more market-driven and interdependent. Its death was sealed by the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct), but PURPA’s raison d’être remains: to promote the use of renewable energy, eliminate monopolistic market practices, and improve America’s overall energy efficiency.

Although we all approve of those objectives, the path forward remains uncertain. At no time in U.S. history have the options for generating power been so plentiful and the opinions of what is environmentally acceptable so divergent. Never have regulators and utility executives disapproved new plants based on expected legislation, rather than laws on the books. Financial uncertainty slowed new projects after the gas bubble burst in 2001. Future projects now must deal with regulatory uncertainty and other threats (see sidebar, “Top 10 strategic business risks facing U.S. power generators”) just as reserve margins in some regions are declining to worrisome levels.

Uncertain prospects for “acceptable” generation haven’t reduced America’s seemingly insatiable appetite for all things electric. Two months ago, the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicted that consumption would grow 2.1% in 2007 but slow to a 0.5% increase in 2008 (Figure 1) as the effects of energy efficiency and other demand-side reduction programs kick in (see sidebar, “Utilities to invest more in energy efficiency”). However, demand continues to rise at double-digit rates in several regions that saw record peaks last summer. Although residential electricity prices are expected to stabilize at a 2% growth rate in 2008 after a two-year spurt (Figure 2), look for significant increases in subsequent years due to more use of costlier, cleaner fuels.

1. Demand growth often down, but never out. America’s electricity consumption continues its slow rise. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

2. Moderate price hikes. Residential electric bills are expected to be 2% higher this year than they were last year. Further out, they will certainly rise much faster if mandatory carbon caps force power producers to use costlier, greener fuels. Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Nuclear projects inch forward

Will 2008 see the kickoff of the much-anticipated U.S. nuclear power revival? The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) thinks so. According to the Associated Press, the agency has hired 400 new employees to handle what it believes could be a deluge this year of applications for combined construction and operating licenses (COLs) for new reactors. So many more paper-pushers will be needed because the COL process is new and has yet to have its efficacy and efficiency tested.

Bill Borchardt, head of the NRC’s new Office of New Reactors, told the wire service that the regulator expects to receive 29 COL applications over the next three years. “We have never had to do this many reviews at one time in parallel,” he said. The AP story said Borchardt’s office “is nearly as large as the NRC unit overseeing the country’s existing 104 commercial reactor fleet.”

The NRC decided it would need to hire an army of application reviewers after receiving numerous expressions of interest in building new reactors. EPAct contains a host of goodies for new nukes, including protections against cost overruns, a 1.8 cents/kWh production tax credit (previously limited to renewables), and federal loan guarantees for up to 80% of the cost of a new plant. By the way, the loan guarantees apply to virtually every type of generation under the sun, including clean coal plants, factories building fuel-efficient vehicles, cellulosic ethanol plants (including the country’s first commercial plant in Georgia, developed by Range Fuels with a total DOE investment of $76 million), and the full spectrum of renewable energy technologies.

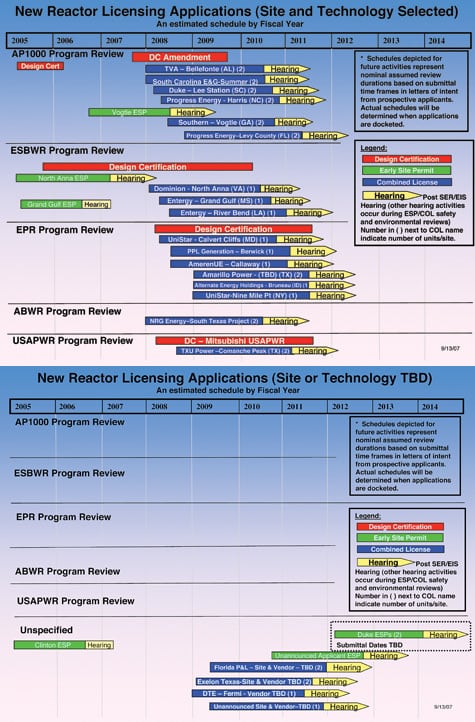

But we’ve been here before—recently. Many in the U.S. nuclear industry were touting 2007 (technically, the start of Fiscal Year 2008, which began October 1) as the start of their industry’s renaissance. It didn’t quite happen. As this story was being researched, in early December, the NRC had received three COL applications and was expecting seven more to be filed by the end of FY 2008 (Figure 3).

3. Get in line. This estimated schedule by fiscal year shows new reactor licencing applications by site and technology. Many applications have been submitted, but there’s been little real progress so far. Source: U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission

How many new reactors?

At the ELECTRIC POWER Conference & Exhibition in Chicago last spring, the moderator of one of the nuclear sessions, Dennis Demoss, of the contractor Sargent & Lundy, asked each of the panelists representing reactor vendors to predict how many COL applications would be under review by the NRC when the trade show opens its doors in Baltimore in May 2008. The forecasts ranged from eight to none.

The prediction of “none” came from savvy Tom O’Neill of General Electric. Is realism trumping marketing hype?

In September 2007, NRG Energy Inc. (notably, not a nuclear utility) filed a COL for two new units at the existing South Texas Project. The application specified use of GE’s ABWR (advanced boiling water reactor), a design that has already earned NRC approval. A month later, Tennessee Valley Authority applied for a two-unit COL to build two Westinghouse AP1000 reactors at its Bellefonte site in Alabama, where 14 years of construction left two Babcock & Wilcox reactors unfinished and deemed unneeded by a 1988 prediction of lower-than-expected demand growth (see POWER, December 2007, Global Monitor). Then, in November last year, Dominion applied for a COL for a 1,520-MW General Electric-Hitachi ESBWR (the ES stands for “economic simplified”) to join two units at its North Anna, Va., site.

Could 2008 be another bust for the nukes? One wise veteran of the nuclear industry predicts that most of the action in Washington and in the nuclear marketplace this year will involve applications for license extensions for existing plants, rather than for COLs for new nukes.

Entergy Corp., an aggressive supporter of new nukes, had been widely rumored to be readying a COL application for 2007. It didn’t apply. According to a well-placed source, the company will sit out 2008 as well. Recently, news surfaced in the trade press of a dispute between Entergy and GE over the choice of the ABWR for a future plant. That chatter may just be the cover for a strategic Entergy decision to put its new nuclear plans on hold.

Nor is the number of COL applications a reliable measure of the nuclear rebound. Though COL applications take millions of dollars to prepare, that tiny ante only gets you a seat at the nuclear regulatory poker table. The big expenditures are still to come, and companies that have submitted COLs may change their mind without much financial penalty.

Nuke market FUD

The market for new nukes in 2008 is beset by the tactic IBM marketers used in the company’s heyday to bewilder competitors: FUD. That stands for “fear, uncertainty, and doubt.” There’s a one-word explanation for the FUD in the nuclear plant market: politics.

Nuclear is the most intensely political of generation technologies (although coal is making a strong bid for the lead), and the politics tend to be partisan. Democrats generally are averse to the atom, while Republicans as a whole are fond of fission.

This year we’ll watch the quadrennial political Super Bowl as the nation elects a president and vice president, all 435 members of the House of Representatives, and one-third of the U.S. Senate. At this early stage of the game, most political pundits are predicting that a year from now, the Democratic Party will have power it hasn’t had since 1993: one of its own in the White House and control of both the Senate and the House.

That’s not a given; plenty can happen between now and this November. But prospects don’t look good for the GOP, and that means they don’t look good for new nukes. The U.S. nuclear industry decided—even before the 2006 elections, which produced a Democratic majority in both houses of Congress—to bet the radioactive ranch on the GOP. The nuclear industry lobby was, to use a waterskiing and snowboarding term, “goofy-footed” by the Democratic tsunami—caught with its right foot in the forward binding.

Eight years of Republican control of the White House, and 12 of Congress, haven’t delivered for nuclear power. As one nuclear lobbyist, speaking anonymously for fear of losing his job, told POWER, “We’ve had the most pro-nuclear administration in 20 years. During its reign, not a spade of dirt has turned on a new plant. The schedule for the nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain has slipped another 12 years. The Department of Energy has been unable to turn the promises of the 2005 Energy Policy Act into realities. It’s a failure of monumental proportions.” Put Yucca Mountain in that same category (see sidebar, “Clinton, Obama agree: Death to Yucca Mountain”).

When Republican President Gerald R. Ford faced a different kind of energy crisis in mid-1970s (the result of the Arab oil embargo), he and the Democratic Congress worked together to serve up an attractive plate of goodies for new nukes. When Democrat Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, the menu instantly changed to gall and boronated wormwood. According to the anonymous lobbyist, the U.S. nuclear industry began melting down in 1976 with Carter’s election, not in 1979 with Three Mile Island. “I was there,” he said. “As soon as Carter made his selections for the NRC, the industry crashed.”

Nukes face stiff political wind

A new Democratic administration isn’t likely to push licensing of new nuclear plants. Indeed, the nuclear industry’s worst regulatory nightmare is very much a political possibility: NRC Commissioner Gregory Jaczko becoming the agency’s chairman. Jaczko, a very bright and sharp-elbowed political player, is considered “Harry Reid’s guy” at the NRC.

A PhD physicist, Jaczko came to Congress as a science fellow working for Rep. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), one of the most anti-nuclear members of Congress over the past 30 years. Jaczko decided he liked Washington and became Reid’s chief advisor on nuclear waste issues. Reid has vowed to kill Yucca Mountain, and he may be able to keep his promise come January 2009. Jaczko professes, no doubt honestly, that he is not anti-nuclear power.

But Jaczko has every reason to be anti–nuclear industry. The Nuclear Energy Institute tried, and failed, to block his initial appointment to the NRC when he won a recess appointment—as did Republican Peter Lyons, a former advisor to former Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee Chairman Pete Domenici (R-N.M.). That was a deal the White House and Reid negotiated, over the objections of the nuclear lobby.

Then the nuke reps tried to derail Jaczko’s nomination to fill a full term last year. They failed. Recently, the nuclear lobby tried to abort a second term for Jaczko. They were unsuccessful. Said our lobbyist, “We’ve tried to screw this guy three different times and failed. How understanding and helpful is he going to be when he runs the NRC?” There’s little doubt that if the Democrats reclaim the White House, Jaczko, the only Democrat on the commission, will become its chairman.

The industry’s political support in Congress has diminished substantially recently. Domenici, the nuke lobby’s leader in the Senate, is a spent force. He’s ill and sometimes unfocused, and he’s announced he’s stepping down at the end of 2008. The second-most-ardent nuke supporter in the Senate is Idaho Republican Larry Craig. His political career is apparently in the toilet. In recent years, the number-three supporter was Wyoming Republican Sen. Craig Thomas, a buddy of vice president Dick Cheney. Thomas died last year. There are no important nuclear stalwarts on the Democratic side of the House or Senate.

The politics of nuclear power will manifest themselves directly in financial markets. It won’t matter how badly a utility wants to build new nuclear capacity if it can’t convince lenders their investment is a safe one. No one is going to risk $5 billion or more on a new plant without assurance of at least capital recovery plus a return. For most generators, it’s a bet-the-company gamble.

So while the politics of new nukes look bad, their short-term financing outlook isn’t very promising, either. An October study of the U.S. industry by Moody’s Financial Services concluded that “there can be no assurances that tomorrow’s regulatory, political or fuel environment will be as supportive to nuclear power as they are currently.” The NRC’s 42-month COL process, Moody’s noted, “remains untested.” Opponents of nukes are likely to litigate NRC decisions, adding time, money, and doubt to the process.

Most ominously, Moody’s suggests that the current estimate of the average cost to build a reactor and start it up by 2015—around $3,500/kW of capacity—is pie in the sky. A more realistic all-in cost for a new reactor, says the bond rating agency, is in the $5,000 to $6,000/kW range. That’s considerably more than conservative estimates for new integrated gasification combined-cycle (IGCC) coal plants. American Electric Power (AEP) estimates its planned 600-MW IGCC plant will cost $3,500/kW.

Coal’s progress slowed

If nuclear has another losing hand in 2008, will that make coal a winner? Maybe, maybe not. It’s another case of the political correctness of generation. Coal—and its link to CO2 emissions—has become at least as un-PC as nuclear power.

Last year opened with good prospects for coal for three reasons: its superior economics, more-efficient ways to burn it (such as supercritical boilers), and slowly improving prospects for CO2-capturing IGCC plants. TXU had an ambitious plan to build 11 conventional coal-fired plants to serve the booming Electric Reliability Council of Texas wholesale market (the same market NRG is targeting with its nukes). Tampa Electric, which already operates a DOE-subsidized 260-MW IGCC unit in Florida, was saying it would build another of 630 MW valued at $2 billion by 2013.

Other coal-fired projects popped up consistently during the early months of 2007. Then the pace slowed in response to stepped-up environmental opposition, concerns about future greenhouse gas regulation, and spotty support by state regulators.

By the end of the year, many of the early ambitions for coal had faded. As part of a leveraged buyout orchestrated by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. to take the company private, TXU agreed to scrap all but three of its planned coal plants. Local activists opposed to the utility’s coal-based strategy persuaded KKR that green protests and litigation would delay or derail the buyout unless the utility scaled back its plan.

The tactics used by environmentalists against coal projects around the country were clever. If a utility or IPP proposed a conventional coal-fired plant, they argued to local regulators that it shouldn’t be approved unless the developer promised to make it capable of capturing carbon. If the developer agreed, the plant’s opponents would demand that the project abandon pulverized coal in favor of the cleaner but untested IGCC technology.

IGCC reality strikes

Then, market realities took hold. A refinery-like process, IGCC is inherently much more expensive than conventional combustion of coal or gas. What’s more, the economics of capturing and storing carbon are as unknown as the technologies are unproven; no currently operating plant can do both.

Nor does anyone really know what to do with the CO2. The multisyllabic buzzword is “sequestration,” meaning “put it somewhere out of sight.” Where? There’s no shortage of suggestions: in salt caverns, in old coal mines, into oil and gas reservoirs to boost their output, under the seabed, under your mattress. How about shooting the CO2 into outer space? If the gas isn’t permanently stored, it will eventually find its way back into the atmosphere.

Veterans of prior decades’ energy debates are reminded of the long, fruitless discussion about what to do with spent nuclear fuel, aka high-level nuclear waste. Bury it in salt caverns? Dig a hole in Nevada? Bury it in seabeds? Shoot it into space? Yucca Mountain notwithstanding, there’s no real answer yet, other than to keep the waste at plant sites.

The question of CO2 disposal, at least in terms of volume and weight, is much bigger than that of what to do with spent nuclear fuel. There’s a heck of a lot more CO2 coming from fossil-fueled plants than fatigued fuel from nukes. The nuke waste is solid, making it easier to handle than gaseous CO2.

Like nuclear safety and spent-fuel storage, coal’s CO2 emissions have become intensely political, although not particularly partisan. Democrats (New York Governor Eliot Spitzer), Republicans (California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, Florida Gov. Charlie Christ, Arizona Sen. John McCain), and independents (Sen. Joe Lieberman of Connecticut) alike are telling gencos they can’t use coal if they can’t hide the CO2 somewhere.

In California, the state legislature, with the governor’s backing, passed a law that not only continues a decades-long ban on coal burning in the Golden State but also puts an end to utilities (including municipals) buying power generated by coal in other states, as they have done for generations. In Florida, Christ’s contempt for coal led Tampa Electric to scuttle its new IGCC project.

The New York Times reported in October that in the Rocky Mountain West, where energy development has long been a favored land use, “An increasingly vocal, potent and widespread anti-coal movement is developing” as ranchers and farmers join with traditional environmentalists to resist coal-fired projects. Also joining the no-coal coalition are ski resort operators, retired homeowners, and religious groups, the Times reported.

The Times article quoted Rick Sergel, CEO of the North American Electric Reliability Corp., the nation’s reliability watchdog. He said, “It’s clear new coal-fired generation is running into roadblocks. I don’t believe we can allow coal-fired generation to become an endangered species. We simply must use all the resources we have.”

That’s not how environmental groups see the constant battle to ensure that supply matches demand. According to the Sierra Club’s Bruce Niles, who runs the group’s national campaign again coal, his group and others have worked together to file 29 administrative actions and lawsuits against proposed coal plants.

Not all have succeeded, of course. Peabody Energy’s Prairie State Energy Campus, a proposed 1,500-MW mine-mouth project in southern Illinois, has survived a withering legal attack and now looks like it will indeed get built.

Coal projects sidelined

A DOE report (www.netl.doe.gov/coal/refshelf/ncp.pdf) released late last year contained mostly bad news for coal generation. Of 12,000 MW of new coal-fired capacity announced in 2002 for expected commissioning in 2005, only 329 MW actually got built. According to the report, during an average year between 1997 and 2006, only 293 MW of new coal-fired generation came on-line.

Still, the DOE says it believes a fair—but unspecified—share of the 23,000 MW of the coal plants it considers “progressing” (either permitted, near groundbreaking, or under construction) may get built. Said the report, somewhat ambiguously, “Progressing plants have a higher likelihood of advancing toward commercial operation, however there is still a degree of uncertainty in these projects.”

Last year’s trade press was full of reports of such coal projects getting delayed and cancelled:

- In South Dakota, two of the seven major partners in the 630-MW Big Stone II project, representing 28% of its ownership, have pulled out, while a major muni, Rochester (Minn.) Public Utilities, has said it will not be an equity partner. Rochester may buy some of the plant’s output.

- In 2004, Duke Energy proposed building two 800-MW supercritical coal units to help meet growing regional demand. Last February, the North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC), not known as a patsy for green groups, approved only one, citing excessive costs. Duke is considering abandoning the entire project, according to trade press reports.

- In September, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission rejected a coal project proposed by AEP and OGE Energy. The utilities had proposed capturing its CO2 and using it to enhance oil and gas recovery from the state’s elderly fields. The rejection caused Southern States Energy Board chief Kenneth Nemeth to note a “groundswell of movement away from fossil energy,” according to the Foster Electric Report.

- In Florida, a month before Tampa Electric pulled the plug on its $2 billion IGCC plant, the state public service commission gave a thumbs-down to a Florida Power & Light Co. plan for a coal-fired plant in Glades County. That led a municipal joint action agency in the Sunshine State to mothball plans for an 800-MW coal-fired plant in north Florida.

- In November, Idaho Power shelved the portion of its integrated resource plan that called for 250 MW of new coal capacity. The utility cited rising costs and uncertainty about greenhouse gas regulations as the reasons.

Perhaps most disturbing to developers of coal plants was an October rejection by the Kansas Department of Health and Environment of an air permit for a $3.6 billion, two-unit, 1,400-MW plant proposed by Sunflower Electric Power, a rural electric generation and transmission cooperative. The sole reason for the rejection, said Roderick Bremby, head of the state agency, was CO2. He said it would be “irresponsible to ignore emerging information about the contribution of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to climate change and the potential harm to our environment and health if we do nothing.”

The Kansas decision is ripe for litigation, according to experienced Washington energy lawyers. While the Supreme Court last year ruled that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has the authority to regulate CO2 emissions under the Clean Air Act, the EPA has not issued regulations. So, according to industry environmental lawyers, Kansas will have a hard time arguing that it has authority to regulate in the absence of an EPA regulatory regime.

Nonetheless, the Kansas ruling troubles the generating industry, suggesting that the assault on coal will continue and the ferocity will increase. Washington energy consultant Roger Gale told the Baltimore Sun recently, “Coal is a tough sell, and clean coal is getting comparable to a nuclear plant” in capital costs.

The real growth in coal-fired generation in 2008 will take the form of plant upgrades and efficiency improvements to extend plant life and increase capacity factors.

If not coal, then what?

Gas-fired plants regain the advantage

For the past five years or so, the big story in U.S. power generation has been the retreat from natural gas, which was the fuel of choice in the 1980s and 1990s. Gas, long in surplus (remember the “gas bubble?”) and featuring steady and declining prices, was the ideal generating fuel for the end of the 20th century. Generators could build low-capital-cost units and arbitrage the different market prices for gas and electricity—the “spark spread”—at will. So build they did, because the economics continued to favor gas.

With low plant upfront costs and short construction times, natural gas dominated. Though gas is costlier than coal on a $/Btu basis, the low heat rates of combined-cycle combustion turbine plants minimize the premium as they operate. The emissions profile of gas plants looked good, particularly compared to coal. Through the ’90s, environmentalists gave gas a pass, seeing it as the transition fuel to a renewables future.

That changed around the end of 2001 (about the same time as the fall of the House of Enron). Gas inventories plummeted, in part due to the collective demand of all those new combined-cycle plants. Prices became volatile. Generators that had dashed to gas now fled from it. Scores of gas-fired projects announced late in the gas boom never made it off the drawing board.

Today, gas has regained some of its glitter. As crude oil prices surged above $90/bbl, the alleged linkage between the prices of oil and gas proved to be a myth. Gas prices have stabilized. They appear to have leveled off at around $7 per thousand cubic feet—well below the prices seen earlier this decade.

As a result, gencos are again considering natural gas plants their least-risky option, in light of gas plants’ low capital and construction costs and the political incorrectness of the nuclear and coal alternatives. Randy Zwirn, CEO of Siemens Power Generation, told an industry meeting last year, “By default, the only technology that’s going to be available is gas-fired generation.”

Although attention recently has focused on new nukes and cancelled coal, gas has been showing stealth strength. A recent EIA report noted that natural gas–fired generation “showed the highest rate of growth from 2005 to 2006 of the traditional energy sources,” accounting for 20% of all new generation in 2006. Compared to 2005 figures, said the EIA, gas-fired generation in 2006 grew by 7.3%, while nuclear grew by 0.7% (due to upratings and better plant performance) and coal fell by 1.1%.

Increasing gas reserves fuel optimism

Is enough gas available to supply new power plants as well as residential and industrial furnaces? Last October, the DOE’s Potential Gas Committee, a group of volunteer energy experts, issued a new estimate of recoverable domestic gas reserves that is 17% higher than one made in 2004. The committee said the U.S. has some 1,525 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas, compared to its 2004 estimate of 1,308 tcf.

That’s the largest increase since the committee started estimating reserves in 1964, according to The Energy Daily (like POWER, an Access Intelligence publication). The committee said new reserve estimates exceed the 36 tcf of gas that U.S. producers extracted between 2004 and 2006.

Meanwhile, the 2007–2008 winter assessment by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) found, “For the second year, the prospects for natural gas markets as we head into this winter are very good.” FERC staffers said gas storage is “robust,” winter temperatures are forecast to be mild, new pipelines and liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals are coming on-line, and gas in storage should exceed record levels as winter kicks in.

The FERC staff report concluded, “Basically, we expect to see full storage this year. Effectively full storage goes a long way toward protecting the country from the disruptions and price spikes associated with tight supply/demand balances in the winter.” If the forecasts for a warmer-than-normal winter are accurate, said the report, “gas prices could remain stable or even see some downward pressure.”

Last November, the EIA reported that proved U.S. natural gas reserves grew by 3% in 2006 to 211 tcf. That’s the highest reserve level since 1976, the agency added. The driver of that growth was the use of new drilling techniques that have given explorers access to unconventional gas, such as the Barnett Shale in Texas. According to the EIA, additions to gas reserves in 2006 replaced 136% of the gas produced that year. It was the eighth straight year that proved gas reserves have grown.

Concrete evidence that utilities are not shying away from natural gas comes from Duke Energy, which last summer asked the NCUC to approve up to 1,600 MW of new combined-cycle gas-fired capacity after having its proposal to build the same amount of coal-fired capacity turned down. Florida utilities are also looking seriously at new gas units, likewise following rejection of coal-fired plants.

A most unusual gas-fired plant has been proposed by Basin Electric Power Cooperative, a large generation and transmission co-op based in Bismarck, N.D. In late October 2007, Basin said it would like to build and commission a 300-MW unit in the eastern part of the state by 2012. At the heart of Deer Creek Station would be a simple-cycle combustion turbine generator and a heat-recovery steam turbine generator. Both would run about 12 to 16 hours a day in intermediate service, following load on the systems of the distribution cooperatives that Basin supplies.

What’s unusual about that? Nothing. However, Deer Creek would burn synthetic gas (syngas), rather than natural gas. The supply would come from Basin’s Dakota gasification project, which uses Lurgi technology to turn lignite into syngas that then can be transported by the Northern Border Pipeline. Developed in the 1980s, the Dakota project is America’s only large-scale converter of coal to gas. The fact that it has never been replicated in the U.S. suggests that there are cheaper ways to go.

LNG lags behind

Early last year, there was buzz about liquefied natural gas. By the beginning of 2008, it had quieted to a murmur. Ambitious LNG projects became stalled as a result of intense local opposition and stabilization of the conventional U.S. natural gas market.

According to FERC, five LNG receiving terminals with a total capacity of about 6 billion cubic feet (bcf) per day operate in the U.S. today. The agency has approved another 21 projects but acknowledges that most of them will never be built.

For example, California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in May last year rejected a plan for an $800 million LNG terminal off the Southern California coast proposed by an Anglo-Australian company. Earlier, the California Coastal Commission had unanimously rejected the project.

Nor does there appear to be a crying need for LNG in today’s market. A Reuters story last October noted that LNG imports to the U.S. were expected to continue a slide begun several months earlier, “as steady demand from the Far East and early buying from Europe soak up more spot supplies.”

According to the Houston-based consultancy Waterborne Energy, U.S. LNG imports in September 2007 were about 45 bcf, or about half the 89 bcf imported in August 2007. The firm’s estimate for October was less than 45 bcf. Weather was partially responsible, said Waterborne. While unseasonably cool weather in the UK raised natural gas prices to about $9/mmBtu, a mild autumn in the U.S. Northeast saw gas prices drop to about $6/mmBtu at the Henry Hub market. The LNG flowed to the UK.

In their forecast of natural gas markets for 2007 and 2008, FERC staff portrayed LNG as a swing resource. According to FERC’s director of gas market oversight, Steve Harvey, LNG acts as insurance. “Depending on international gas prices,” he said, “supply may or may not be available to U.S. markets.” So much for the LNG boom.

Renewables ahead by a nose

Wind power has been soaring for several years, driven by state mandates (renewable portfolio standards) and federal subsidies (the production tax credit). But the boom represents a start from a tiny base; wind power remains a miniscule contributor to the national electric supply. Considering its inherent dispatchability problems (wind is intermittent) and the need for backup generation if the resource is to be a major contributor to total U.S. supply, wind’s future could be summed up as positive but limited.

In November, the American Wind Energy Association (AWEA) upped to 4,000 MW its earlier prediction that 3,000 MW of wind power would be added to U.S. grids in 2007. Either number would top the 2006 record of 2,454 MW. In its second-quarter report on the state of the generation niche, America’s biggest wind power promoter said 935 MW of capacity were commissioned during the quarter, bringing first-half 2007 capacity additions to 1,059 MW. In the third quarter alone, 1,251 MW of wind power were added, including 600 MW in Texas alone.

But there is a supply-chain cloud on wind energy’s horizon, according to AWEA. The news release announcing the Q2 report warned, “Wind power developers report that turbine availability is a limiting factor—in other words, there is demand for even more wind energy but companies can’t build more projects because there aren’t enough manufacturing facilities for turbines and turbine parts in the country because the U.S. government’s intermittent policy toward renewables has discouraged companies from investing in manufacturing facilities.”

If conventional economics holds, the shortfall in the supply of wind turbines will raise the cost of wind farm construction. However, unmet demand for ingredients common to all power projects—concrete, rebar, steel, labor, and other commodities—are bidding up their costs, too. It’s a sellers’ market, which further undermines the economics of wind power.

That highlights a policy problem for wind. Congress refuses to make a long-term commitment to the 1.8 cents/kWh production tax credit for renewable energy plants. The view of many legislators is that the credit should be a short-term subsidy to help the industry reach commercial viability, as opposed to a permanent entitlement.

The wind industry sees the sop differently. Said Randall Swisher, AWEA executive director, “What is critical at this juncture is for the U.S. government to put in place a full-value, long-term extension of the production tax credit and a national renewable energy portfolio standard requiring that utilities generate more electricity from renewable sources. These policies will give the clear, big-picture signal of support for renewable energy that this country urgently needs.”

Renewable resources technologies as a whole aren’t proliferating nearly as quickly as wind power. According to the EIA, wind generation grew from 3,684 MW in 2001 to 8,706 MW in 2005. But the entire category of renewable energy generation grew only from 95,096 MW in 2001 to 98,791 MW.

The vast majority of American renewable-fueled power production (using the EIA’s definition) comprises conventional hydro plants, the bane of most mainstream environmentalists. Hydro’s heyday here seems to have passed; no one is proposing new projects and old ones are fading away. In 2001, big hydro generated 78,916 MW; in 2005, the figure was 77,541 MW.

Other renewable generation technologies—photovoltaic arrays, biomass combustion, and geothermal energy extraction—remain trivial and slow-growing. Nationwide, solar electric generation accounted for 392 MW in 2001 and 411 MW in 2005, and just a handful of larger projects are on the horizon. Biomass generation—from plants burning wood, wood waste, and municipal solid waste (including landfill gas)—made the slimmest of gains: from 9,708 MW in 2001 to 9,848 MW in 2005. There is little evidence to suggest that any of these proven renewable fuel technologies will grow substantially in 2008. However, some of their less-conventional brethren are enjoying major development funding (see “Google this: ‘Clean and cheap power’ ”).

Your turn

There you have it—our thoughts about what to expect in 2008. We’ve given you the best information and data available, and we encourage you to use them to form your own opinions about U.S. generation options. We haven’t been shy about telling you what we think, and we hope you’ll repay the favor. Send your comments to editor@powermag.com and we’ll publish the most interesting letters.