If the Clean Power Plan is scrapped or weakened, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) may be forced to regulate greenhouse gases (GHGs) emitted by existing power plant with wider repercussions under its National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) program, experts have warned.

While President-Elect Donald Trump promised to “scrap” the Clean Power Plan during his presidential campaign, the power sector has grappled with regulatory uncertainty since the Supreme Court issued a stay of the rule that establishes the first federal GHG limits for existing fossil fuel–fired power plants in February 2016. The rule, finalized in 2015 under Section 111 (d) of the Clean Air Act, has deeply divided the nation and U.S. power sector.

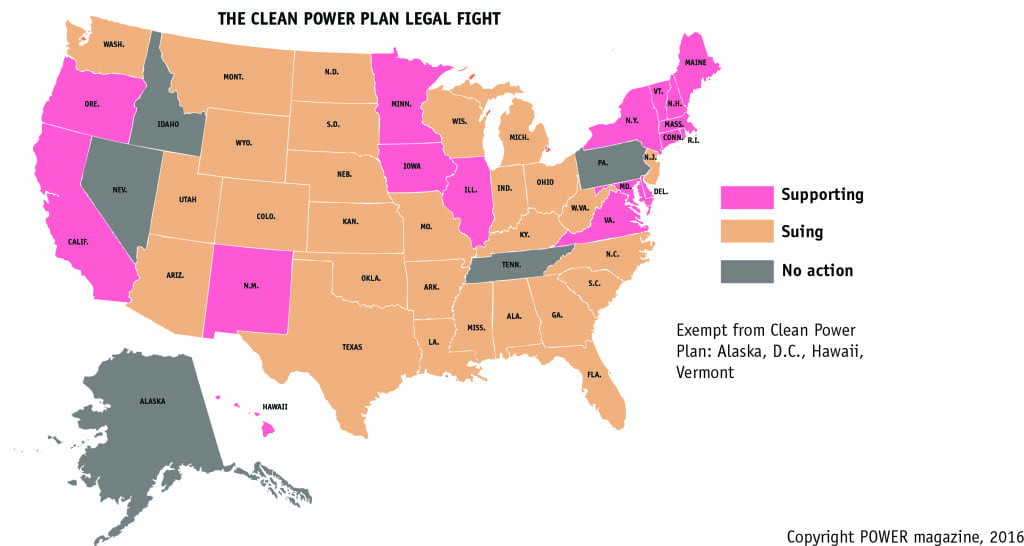

Eighteen states (plus the District of Columbia) supported the rule in the merits litigation: California, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia, Vermont, and Washington. A number of power companies are also participating as intervenors, including Calpine, Pacific Gas & Electric, NextEra, and Southern California Edison Co.

Meanwhile, 27 are suing the EPA: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Oral arguments on the merits of the rule were recently concluded before an en banc panel at the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Litigation on the rule could result in a number of possible outcomes, note authors of a new working paper by Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions and the University of North Carolina’s Center for Climate, Energy, Environment & Economics. If the D.C. Circuit upholds the rule in whole, the Trump administration may choose to create a new rule that repeals or weaken GHG limits for existing power plants.

But, “If the ultimate decision is that the EPA either cannot regulate existing fossil fuel-fired power plants under Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act or cannot include generation shifting when setting the rule’s stringency, then stakeholders may seek to use NAAQS,” the paper’s authors said in a briefing issued to the press. “Further, President-Elect Donald Trump has stated he would ‘scrap’ the Clean Power Plan. If he does, then stakeholders would likely sue, seeking to force the EPA to use the NAAQS program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The working paper, which the authors released on January 5 to “inform debate on emerging issues,” notes that the Supreme Court’s landmark decisions in

Massachusetts v. EPA and American Electric Power v. Connecticut give the EPA the authority to regulate GHGs under the Clean Air Act. “Given legal precedent outlining this authority and the existing endangerment finding, stakeholders may litigate to force the EPA to regulate these emissions under other Clean Air Act authorities, such as the NAAQS program,” the paper says.

Various options were detailed by the EPA in an advance notice of proposed rulemaking issued during the George W. Bush administration on how it could regulate GHGs under the Clean Air Act discuss Section 111, Sections 108–110 (the NAAQS program), and Section 115, it notes. “Stakeholder groups have petitioned the EPA to regulate greenhouse gases under the NAAQS program, and that petition still sits undecided within the EPA.”

Moreover, the triggering tests for regulating under this program require that a pollutant “endanger public health and welfare” and come from “numerous or diverse” sources. Greenhouse gases satisfy these two tests, the paper’s authors noted.

If the EPA were to take the NAAQS route to issue a new rule regulating GHGs from the existing fleet, it could look a lot like the Clean Power Plan. “The language of the Clean Air Act gives states and the EPA a lot of flexibility to implement the NAAQS program for specific pollutants meaning that states and the EPA could take many of the same mechanisms from the Clean Power Plan and apply them to the power sector in a NAAQS implementation plan,” they said. “In fact, Section 111(d) of the Clean Air Act relies on NAAQS-like state plans that are sector specific.”

A NAAQS route would also allow for states to create “trading ready” plans. Meanwhile, a NAAQS program could build on the trading options of the Clean Power Plan “because it applies economy wide, and thus could include multi-sector trading rather than a narrowly confined category of sources, like those of Section 111,” they said.

However, the EPA could run into a number of challenges, the paper notes. The EPA likely opted not to develop NAAQS for GHGs because the NAAQS program is “highly detailed,” and it was written with localized pollutants in mind. To fit GHGs into the structure of NAAQS could require the EPA to address a “number of thorny issues,” the authors said.

“For example, even small sources emit large levels of greenhouses gases that may require them to obtain permits under the program. Thus, the program will be challenging without effective streamlining for these small sources that’s legally acceptable.”

Additionally, most greenhouse gases are “well-mixed,” meaning their concentration is similar around the world regardless of where the emissions arise. “Given this characteristic, the level where the EPA sets the NAAQS standard matters a lot because all states would be either in or out of compliance with the standard. Moreover, because international emissions affect the global concentration level, states have limited control over their state’s specific greenhouse gas concentration level,” they added.

—Sonal Patel, associate editor (@POWERmagazine, @sonalcpatel)