This story is being written as world leaders gather in Paris for the COP-21 climate summit. Much of the reason they are meeting is because of the widespread burning of coal and the resulting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions that are altering the planet’s biosphere. Though the burning of coal is not the only reason the world’s atmosphere is heating, it is one of the leading causes. Curtailing the use of coal to generate electricity is widely seen as key to the reduction of the worst aspects of climate change. Though coal production and dependence is decreasing in many developed nations, more of it is actually being mined and burned worldwide overall.

Since 2000, coal consumption has declined slightly within the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), a club of industrialized countries. But it has risen by 123% in non-OECD countries. Most of this increase has been in China, which accounts for half of the worldwide consumption. Russia as well remains both a large miner and producer of coal, exporting to most of the western European nations that are today pledging to reduce their burns.

In its most recent World Energy Report, the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) stated that “world demand for coal will be reaching a plateau around 2020.” But there are differing trends across OECD and non-OECD regions, with the former declining and the latter continuing to increase. Though, according to the IEA, coal use peaked eight years ago among the OECD, worldwide, over 30% of the total energy demand and over 40% of the total electricity generated comes from coal. The truth is that coal remains the fastest growing source of fossil fuel, adding more to the absolute world energy supply in the last decade than almost all other forms of energy combined.

Overall, global energy-related CO2 emissions stayed flat in 2014 (at an estimated 32.2 Gt) despite an increase of around 3% in global economic output. This is the first time in at least 40 years that a halt or reduction in emissions has not been tied to an economic crisis. Across the OECD, emissions continued to decouple from economic growth last year. But since 2000, the share of coal has increased from 38% to 44% of energy-related CO2 emissions, and over the past two-and-a-half decades, global CO2 emissions increased by more than 50%. While emissions increased by 1.2% per year in the last decade of the 20th century, the average annual rate of increase between 2000 and 2014 accelerated to 2.3%, particularly driven by a rapid rise in CO2 emissions in power generation in countries outside the OECD. But in the same period, total CO2 emissions from the industrial sector in OECD countries fell by a quarter.

The German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources estimates the world’s remaining coal reserves at 968 gigatonnes (968 billion metric tons, mt). In 2013 alone, we globally mined and burned over 8 gigatonnes every second. Of course, not all coal is equal. Anthracite and bituminous coals are comparatively cleaner-burning than subbituminous and lignite coal, the latter of which is much lower in energy content and higher in ash and other impurities. This requires more lignite to be mined and burned to create the same power generating levels. Worldwide, some 37 countries exploit lignite, but only 11 account for 82% of worldwide production. The biggest producer in 2013 was Germany, with 183 million mt, followed by China and Russia.

A New Curtain Between Eastern and Western Europe

But as coal burning declines throughout the comparatively richer OECD, many developing countries continue to embrace it. Ironically enough, perhaps nowhere is this split more evident than in the supposedly united Europe, which many people assume is becoming greener by the day. In fact, as Western Europe reduces its coal usage, the former Soviet bloc nations are moving in the opposite direction. Bloomberg Business calls it a new “Coal Curtain,” as there is a stark divide between the two regions. In the east, Poland and the Czech Republic have both announced an expansion of production of their domestic hard and lignite coal reserves, the dirtiest of all coals. Other European nations like cash-strapped Greece are also investing in new coal production and generation capacity too.

Last month the UK’s energy minister announced a decision by the otherwise conservative David Cameron–led government to phase out all coal burning over the next decade. While Germany has also decided to shut down its hard coal mines even as it slowly phases out nuclear generation, it has actually committed to expand domestic lignite production and the construction of new coal fired plants that will depend on imported as well as domestic supplies.

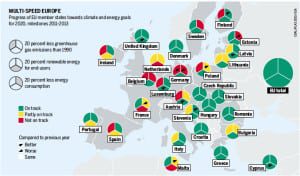

According to the Coal Atlas 2015, jointly published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Berlin and Friends of the Earth International in London, when scientists measured greenhouse gas emissions in 2013, they tallied a roughly 19% decline from 1990 figures. This “success” was mainly due to a series of abrupt mine and power plant closures made within the new eastern European Union (EU) member states at former Soviet-built facilities, combined with the 2008 economic crisis that led to lower energy consumption. Overall, the EU has pledged to reduce emissions by 20% from 1990 levels by 2020; to rely on 20% renewable energy by 2020; and a 20% reduction in overall energy usage (or one-fifth more energy efficiency) by 2020 as well. At the moment the EU is still on track in terms of energy efficiency, and it is making good progress in developing renewable energy. With a 15% share of renewable energy consumption by end users in 2013, the EU has nearly reached its 20% target rate. CO2 emissions actually fell in 2014 despite slight growth in the whole EU economy, proving that it can be done.

But according to the Coal Atlas 2015, only nine of the 28 member states are on course for all their goals (see figure). One reason why their report card is so poor is because several new coal-fired power stations have come on stream over the last few years. That particular trend has now ended, but coal remains an important fuel for Europe. In 2014, one in four kilo- watt-hours in the EU came from coal; 68% of the lignite and 79% of the hard coal came from Germany, Poland, or the Czech Republic. These three countries generate more than half of the EU’s coal power, even though they have only one-quarter of its population.

Great Britain Announces the End of Its Coal Age

Across the English Channel, coal accounted for almost 30% of the UK’s overall power mix in 2014. Though nearly as high as coal’s percentage in the U.S., this figure is actually a 7% year-over-year reduction from 2013. Furthermore, in 2015 renewables overtook coal in the UK’s power mix for the first time.

Domestic coal mining has fallen even more rapidly, but this gap has been filled with imported coal, mainly from Russia, Poland, and the U.S. There are currently only 10 coal-fired power plants operating in the UK. By mid-2016 two more are scheduled to close.

But coal is cheap, and this summer it became apparent that the largest six power producers—including British Gas and SSE—that together account for 40% of the UK energy market, depend more on coal-fired energy today than a decade ago, according to reports published in the Independent. Though over the past 10 years the percentage of electricity generated from renewable sources has grown by 400%, total carbon emissions from generation have only fallen by around 8%. This is because the Big Six energy companies now dispatch more than a third of their energy from coal-fired power stations, while cutting back on buying power from more expensive but greener gas-fired ones. Though bad for the environment, that shift certainly helps with corporate bottom lines.

“In the absence of rules to cut pollution from the dirtiest coal stations it has been very profitable for the big energy companies to burn more coal,” said Joss Garman, associate director for energy and climate change at IPPR in the Independent. “This has been hugely damaging to Britain’s efforts to build a cleaner economy because it has cancelled out some of the carbon savings brought about by the growth in green energy,” said Garman. But, if the Cameron government follows through on recent pledges, this is coal’s last major dance in the UK.

In mid-November, Amber Rudd, the Cameron Government’s energy minister, gave a major speech outlining the government’s new policy around coal. Calling for the curtailment of most coal-fired generation by 2023, the remaining plants are now scheduled go on stand-by through 2025 and close afterwards. The irony, however, is that even as the nation has enjoyed a huge growth in renewables, “our dependence on coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel, hasn’t been reduced. Indeed a higher proportion of our electricity came from coal in 2014 than in 1999,” said Rudd. Now, “after 20 years of action on climate change, 30% of our electricity still comes from unabated coal.” But within a short eight years, that will change drastically.

“I am pleased to announce that we will be launching a consultation in the spring on when to close all unabated coal-fired power stations [those without carbon capture and sequestration]. ” she continued. After announcing these plans, a proud Rudd then told the audience that, “If we take this step, we will be one of the first developed countries to deliver on a commitment to take coal off the system. . . . The policy confirms the move away from coal, which now accounts for only 20.5 percent of total electricity production in the U.K., down from over 28 percent a year ago.”

While acknowledging that coal will remain a necessity for developing countries for a long time, Rudd stated that “there is no reason why developed nations can’t wean themselves off it,” perhaps a nod to Germany, which continues to struggle with a similar coal conundrum.

Going forward, as the UK shutters coal plants and converts others to burning natural gas instead, billions of pounds will be invested in nuclear energy. In the future, combined gas and nuclear fleets will be the backbone of the UK’s baseload electricity. Though environmentalists were excited to see the back of coal, the lack of investments in renewables remains a concern. The Cameron-led government, never mistaken for a green supporter, is still quite committed to fossil energy, fracking, and off-shore oil drilling.

The one small bone thrown out to the industry was that “Any coal-powered plants that are able to install carbon capture and storage, or CCS, before 2025 would get a reprieve.” But at the end of November, Cameron’s government quietly pulled all funding for CCS projects as well, dealing a potentially lethal blow to the industry. Jim Watson, director of the UK Energy Research Centre, said the decision would make Britain’s plan to cut carbon emissions by switching from coal to gas power plants less effective. “Without CCS available, the government’s plans to use gas as a ‘bridge’ to a low carbon future will have much more limited mileage in the medium term,” Watson said. The carbon capture competition had two bidders: the White Rose project to capture 90% of emissions from a coal power plant in Yorkshire in northern England and store it under the North Sea, and a scheme to capture carbon from gas power in Scotland.

More ambitiously, Scotland has pledged to be powered 100% by renewables by 2020. Its once-large coal mines are mostly shuttered, and the remaining coal-fired power plant at Longannet in Fife is currently more dependent on imported fuels than locally sourced coals. But Longannet is scheduled to close at the end of the first quarter of 2016. At the moment, however, the nation still produces several million tons of coal per year from several open pit mines. But mining will most certainly fall from 2 million tons per year today to less than a half a million tons as coal is phased out throughout both Scotland and the UK over the next decade.

Germany Announces the End of Hard Coal While Building More Coal Plants and Approving More Mines

As Germany phases out nuclear power following the disaster at Fukishima, it has come to rely even more on coal for its electricity. Despite a steep rise in renewable energy, its increasing use of coal is now endangering Germany’s ambitious target to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. And while it has decided to shutter its few remaining deep hard coal mines, it is actually increasing its dependence on foreign coal while also expanding its dependence on dirty lignite—the only significant fossil fuel that the country has.

National reserves are estimated at 40 billion mt and are split among three major regions: the Rhineland, eastern and central Germany. Those regions are, for the most part, the poorest in the country. The Rhineland has yet to recover from its transition away from heavy industry and, in the former Communist east, a large financial chasm still exists (despite billions of euros being invested there to bring it to parity) with the former West Germany. Many thousands of jobs still depend on coal mining and burning in those areas. And, to a very large extent, those miners and coal workers vote for the conservative parties that form the bulwark of the current centrist government. German Chancellor Angela Merkel herself was born in the former East Germany, and few know better than she does how important heavy industry is to the region.

In 2014, more than one-quarter of the electricity produced came from lignite, and its output of 178 million mt a year makes Germany the world’s biggest producer. The industry has benefited from 95 billion euros in subsidies (in real terms) since 1970, and open-cast mines have gobbled up 176,000 hectares of land. Current mines cover 60,000 hectares. The federal states that host lignite reserves plan to continue mining well into the 2040s, and plans exist to develop five new mines in eastern Germany (two of which were recently approved). According to the Coal Atlas, if Germany really intends to stick to its target of cutting its greenhouse gas emissions 80% to 95% by 2050, then two-thirds of the lignite reserves already approved for mining must stay in the ground unless emissions will be cut drastically throughout other sectors.

In contrast, Germany’s extraction of hard coal will end in 2018. The three remaining deep mines still produced 7.6 million mt of coal in 2014, and the country continues to generate about 18% of its power from hard coal. Since domestic supply is shrinking, Germany imported more than 42 million mt in 2014 for power stations. Most of this coal comes from Russia, followed by the U.S. Long unprofitable, the nation’s deep mines have been dependent on generous government subsidies since the middle of the 20th century. As those subsidies are phased out in 2018, the mines will finally close.

While the nation has trumpeted the fact that renewables, as part of the “Energiewende,” regularly generate over one-quarter of the nation’s energy (and often much more), on average, lignite and hard coal together generate 44%. Unless things change, Germany is likely to miss its climate goal of 2020 (a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to 1990), mainly because of the increase in coal generation.

With Chancellor Merkel already rapidly losing regional support because of her stance on refugees, her enthusiasm to further alienate her base is certainly waning. Her pledge to close the last of Germany’s eight nuclear reactors by 2022 will also likely require a longer commitment to coal.

Across the Great Coal Divide

In Eastern Europe, across the old fault lines of the Cold War, and in much of the former Communist bloc, coal is the only domestic alternative to oil and gas imported from Russia. Bulgaria still gets almost half of its electricity from coal, and in Serbia it’s about two-thirds. All together, in six former Soviet-bloc countries now in the EU, coal accounted for roughly 39% of the energy consumed last year, according to the BP Statistical Review. By contrast in Western Europe, it accounted for only 12.5%.

As Poland continues to find ways to privatize state-owned mines and open new pits, closing existing mines is particularly contentious. The coal industry there still employs some 100,000 people and helps generate over 80% of the country’s electricity. According to the BBC, over 70% of Polish households also still use coal to heat their homes. Combined, the aging power plants and millions of home coal stoves render Poland’s air some of the worst within the EU. But rock-bottom global coal prices are driving many of the inefficient often antiquated Polish mines into bankruptcy, threatening those heavily subsidized—and politicized—mining jobs.

Following agreements made allowing Poland into the EU, the nation must boost its overall use of renewable energy to at least 15% by 2020 under EU deals on emissions curbs. But it is not at all clear now how Warsaw intends to meet those targets. In fact, Prime Minister Beata Szydlo’s newly elected Law & Justice Party has vowed to negotiate exemptions from a pledge to cut CO2 emissions by 40% by 2030 that the 28 members of the EU—including Poland’s previous government—agreed to a year ago. It’s quite likely they will exploit a carve-out or threaten to distance themselves from other EU commitments. “We obviously want to protect the climate, but only to the point that it won’t hurt the Polish economy,” Szydlo said before traveling to Paris for the big COP-21 climate meeting.

Similarly, in heavily coal-dependent Czech Republic, this past October the government granted the giant Bilina lignite mine permission to exceed limits imposed by a 1991 law that had sought to mitigate the environmental devastation wrought by decades of Communist rule. “This is a responsible decision that takes into account the energy security of our country,” Czech Industry and Trade Minister Jan Mladek said after the government extended Bilina’s lifespan. Despite a push from Western Europe to limit coal consumption, “electricity will have to be produced somehow,” he said.

With some of the deepest mines in the world, eastern Czech hard coal is still prized by steelmakers worldwide and is central to the heavy industry located within the Silesian region straddling the Czech-Polish border. Though used as well to produce electricity, the majority of the Czech Republic’s thermal coal is brown, lignite coal mined in the northern center of the country. That’s where the Bilina mine is being expanded. In a nod to the Communist era, it’s likely that several communities will have to be relocated as giant excavators dig through Earth’s surface to unlock the coal buried beneath.

Long before World War II, both nations were heavily coal dependent, as mainly German- or Austrian-owned companies exploited rich reserves throughout the region. Prized by the Nazis and then the Russians, Czech and Polish heavy industry were central to both regimes. Even today, millions of people and hundreds of millions of euros of investments depend on the cheap energy the heavily subsidized mines provide.

Moreover, during the Soviet era and, to a large extent continuing to the present, regional mines are seen also as job centers (see photo). Through the 1990s, even though many mines are located adjacent to each other, each might employ up to 10,000 people operating redundant transport and outmoded mining systems. Run as local fiefdoms, profitability is only a recent concept in the now-privatized Czech hard rock mines, and it’s still largely an unrealized goal on both sides of the shared Czech/Polish border.

As pressure builds out of Brussels and other EU offices for the nations to return to the green fold, both Poland and the Czech Republic have continued to move further to the right. With Russia openly wooing both back to its orbit and drawing a bright line against further EU and NATO advancement, Western European powers are scared to further provoke their new eastern partners.

Germany Leads Struggling Greece Back to Coal

Just days before the Paris climate summit began, a German NDR public television report on exports of German coal-power technologies, coupled with billions of euros of German state bank funding, once again showed how contradictory Germany’s position on coal remains. Since 2006, Germany’s credit “injections” abroad for coal-fired power amounted to three-and-half billion euros, the NDR investigative television show Panorama reported. Indeed, included in the bailouts and loans Germany has offered to many other EU nations, especially Greece, are dictated terms demanding reinvestment in coal and backing away from renewables.

Though Germany’s coal technology export drive ran counter to the German public’s belief that the federal government was a climate protection trendsetter in promoting wind and solar power generation, said Panorama, nonetheless, lenders have been backing new “clean coal” burning power stations. These power plants, often constructed instead of less-polluting gas-fired plants, will likely produce twice as much CO2 as an off-the-shelf combined cycle plant. And, in Greece at least, the loans to build these plants are choking out any opportunity to construct new solar facilities or renewable plants at all.

Panorama cited the new Ptolermaida coal-fired power station as a case in point. Due for completion in 2019 and being built in northern Greece by Hitachi Europe, a company based in the German city of Duisburg, the project is funded almost entirely via a 730 million euro ($776 million) loan from Germany’s taxpayer-funded KFW development bank. But without the German loan contribution, “the project would not have come about,” said Vasilis Kikis, a professor at the technical university in the northern Greek city of Kozani. “It binds us for decades to the use of coal-fired electricity,” said his mine engineering colleague, Professor Lazaros Tsikritzis. “We are in position one or two in Europe for potential solar energy.”

In fact, since the financial collapse in Greece, Germany has bound that country not only to new tax schemes, but also to outmoded German coal-based technologies. The technology being more or less forced upon Greece isn’t even cutting edge. In the meantime, Greece’s once ballooning solar industry has entirely crashed. “The most important raw resource for Greece is not the brown coal but the sun and the wind,” added Kikis. Germany’s insistence that the nation accept redevelopment loans for new coal-fired plants forces the nation to remain dependent on central generation, instead of distributed energy, and tied to a paradigm that many now see as both outmoded and inefficient, particularly in an ever-less-stable world.

In the East, the Black Russian Bear Still Looms

The Russian Federation has the world’s second-largest coal reserves, and coal is produced in 25 of its constituent territories. According to statistics reported in the Coal Atlas, over half (52%) comes from the storied Kuznetskiy basin, or Kuzbass, in the Kemerovo Region of Western Siberia. Russia’s rising production over the past 10 years has been due to a major buildout there. Prized for both its metallurgical and thermal properties, new mines in the Elga region of the Kuzbass have required billions of dollars in investments in new infrastructure, railroads, ports, electrical power, and steelmaking. One of the investors is none other than Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has taken a keen personal interest in the project.

Nationwide, over 70% of Russia’s coal is currently produced from open-cast mines. The industry, which consists entirely of privately owned companies (that receive various amounts of official and unofficial government support), employs more than 150,000 people directly. For each mining job, there are up to 10 or more other dependent positions. Russia simply doesn’t have another industry to absorb those jobs.

Throughout the vast Russian expanse, more than 170 power plants run on coal. More than 80% of these plants are over 20 years old, and some of the oldest, a few of which date from the Stalinist era, have an electrical generating efficiency of only 23%. New coal-fired plants in Western Europe and elsewhere can achieve 46% efficiency.

Though much of its coal is burned internally, in 2013, Russia was the world’s third-largest coal exporter, after Indonesia and Australia. It ships coal to nearly 50 countries. Ironically, Germany and the UK are its biggest customers in Europe.

Nationwide, renewables are next to invisible. They are regarded as suitable only for places not already connected to the grid. In tightly controlled Russia, there is virtually no political debate on the future of the coal industry. The government sees the sector not only as an important exporter of fossil fuels and as a big employer but also as a key way of generating new capital from abroad, second only to exported Russian oil and gas. Both of the latter have often been used as key tools of foreign “diplomacy” as well. And though many are quick to point out the importance of the Ukraine as a gas transit route, the Ukraine is also a major coal producer.

However, speaking at the COP-21 meeting, Putin shocked many attendees when he began speaking about the reality of climate change’s effects worldwide, including in Russia, where the Siberian permafrost is looking less permanent by the day. Just over a decade ago, he had joked that climate change would actually benefit Russians because they would have to wear less fur coats, as he mocked the very notion that the planet was really warming. For years Putin and other Russian leaders have suggested that climate change was not only a hoax but was also another way to hobble the fossil fuel–rich nation. But as the hottest year ever recorded ends, the realities of physics may force Putin and the Russian Federation to review their practices.

King Coal Still Holds Power

Currently, as COP-21 continues, much of the media is touting the world’s green shift. Indeed, led by Bill Gates, Google, and other investors, billions of dollars have been pledged to build out a renewable future even as trillions of dollars has been divested away from fossil fuel holdings. But coal remains the biggest source of energy worldwide. For those nations that rely upon it, King Coal is fiercely clasping onto power. The further east you travel into Europe’s heartland, the more power he still wields.

—Lee Buchsbaum (www.lmbphotography.com), a former editor and contributor to Coal Age, Mining, and EnergyBiz, has covered coal and other industrial subjects for nearly 20 years and is a seasoned industrial photographer.