The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed two landmarks rules this past week: On Friday, it released regulations that seek to govern mercury emissions from some 200,000 industrial boiler process heaters and solid waste incinerators, and on Tuesday, it issued a long-awaited proposal to regulate coal ash—though it deferred a decision on whether to treat it as hazardous waste.

The Coal Ash Rule

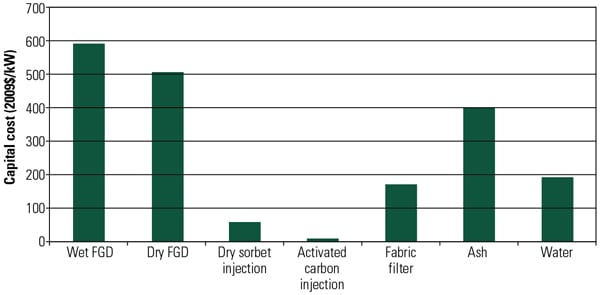

The agency on Tuesday released the first-ever national rules that regulate the disposal and management of coal ash from coal-fired power plants.

The proposal opens a “national dialogue” by calling for public comment on two approaches for addressing the risks of coal ash management under the nation’s primary law for regulating solid waste, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

Under the first proposal, the EPA would list these residuals as special wastes subject to regulation under subtitle C of RCRA, when destined for disposal in landfills or surface impoundments. Under the second proposal, the EPA would regulate coal ash under subtitle D of RCRA, the section for nonhazardous wastes. Both had their advantages and disadvantages, the EPA said, adding that it would choose between the options after the 90-day comment period.

“Today’s action will ensure for the first time that protective controls, such as liners and groundwater monitoring, are in place at new landfills to protect groundwater and human health,” the agency said. Under the rules, existing surface impoundments will also require liners, and there will be strong incentives to close the impoundments and transition to safer landfills, which store coal ash in dry form. The rule also seeks to promote forms of recycling coal ash—both approaches proposed would leave in place the Bevill exemption for beneficial uses of coal ash.

The rules were proposed to ensure stronger oversight of the structural integrity of impoundments in order to prevent accidents like the massive coal ash spill at Kingston, Tenn.

Reports suggest that the breach of the 50-year-old coal ash storage pond and subsequent ash spill at the Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA’s) Kingston Fossil Plant in Roane County, Tenn., in December 2008 was caused by a rare and complex combination of conditions. These included the existence of an unusual bottom layer of ash and silt, the high water content of the wet ash, the increasing height of ash, and the construction of sloping dikes over the wet ash.

An estimated 5.4 million cubic yards of material, mostly hydraulic-filled (wet) ash, were released onto some 300 acres following the sudden failure of the north and central portions of a dredge cell at the 1,700-MW plant’s ash disposal site. The disturbance triggered a floodwater response wave that ran upstream and downstream of surrounding waterways (the TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant is located on the Emory River close to the confluence of the Clinch and Tennessee Rivers). The combined mass of flowing ash and water pushed one single-family home off its foundation and damaged several other homes. No injuries were reported, but cleanup was estimated to cost $1.2 billion.

Coal combustion residuals, commonly known as coal ash, are byproducts of the combustion of coal at power plants and are disposed of in liquid form at large surface impoundments and in solid form at landfills. The EPA said that the residuals contain contaminants like mercury, cadmium and arsenic, which are associated with cancer and various other serious health effects.

The EPA’s stance on the coal ash regulations drew criticism from environmentalists. “We are disappointed that the rule brings forward two dramatically different regulatory options,” Scott Slesinger, legislative director for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said in a statement. “We expect EPA to choose the option that adequately protects the public, particularly our precious groundwater, and treats this hazardous waste as a hazardous waste.”

The agency is now seeking public comment on how to frame the continued exemption of beneficial uses from regulation and is focusing in particular on whether that exemption should exclude certain noncontained applications where contaminants in coal ash could pose risks to human health. The public comment period is 90 days from the date the rule is published in the Federal Register.

The Boiler Rule

The so-called boiler rule, which the EPA proposed at the end of a court-imposed deadline on April 29, could slash overall mercury emissions by more than 50%, the agency said. It also targets a number of air pollutants, including other metals, and organic air toxics, which include polycyclic organic matter (POM) and dioxins.

The rules follow a June 2007 decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit that vacated and remanded standards set by the Bush administration in 2004. The court held that the EPA incorrectly included boilers that combust solid waste in the development of the standards. The court stated that any unit that combusts solid waste may not be included in the development of standards for boilers.

Industrial boilers and process heaters typically burn oil, gas, coal, and biomass—such as those used by factories, universities, and municipal utilities—to make steam, which in turn is used to produce power or heat. These units are the second-largest source of mercury emissions after coal-fired power plants, the EPA said. Last week proposed actions also cover commercial and industrial solid waste incinerators, which burn solid waste.

Under the rules, large boilers and all incinerators would be required to meet emissions limits for mercury, dioxin, particulate matter, hydrogen chloride, and carbon monoxide.

For all new and existing natural gas- and refinery gas-fired units, the proposed rule would establish a work practice standard instead of emission limits. The operator would be required to perform an annual tune-up for each unit. For all existing units with a heat input capacity less than 10 million British thermal units per hour (MMBtu/hr), the proposed rule would establish a work practice standard instead of emission limits. The operator would be required to perform a tune-up for each unit once every two years.

Facilities with boilers would also be required to conduct energy audits to find cost-effective ways to reduce fuel use and emissions. Smaller facilities, such as schools, with some of the smallest boilers, would not be included in these requirements, but they would be required to perform tune-ups every two years.

The EPA has said it would allow 45 days for public reaction, including hearings, which would let U.S. companies object. It hopes the proposed regulations will go into effect by the end of the year.

Sources: POWERnews, EPA