The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Clean Power Plan will certainly be challenged in court, but states and power companies must expend enormous resources developing and complying with state plans regardless of the outcome, witnesses testified on March 17 at a House hearing on the proposal’s legal and cost issues.

The three-hour-long hearing at the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Subcommittee on Energy and Power comprised two panels: The first featured witnesses familiar with the legal implications of the June 2014–proposed rule, and the second, officials from state agencies in Florida, Maryland, Ohio, and North Carolina.

The Cost Chasm

Predictably, witnesses and lawmakers floated varying estimates on how much the proposed rule could cost if finalized. Rep. Ed Whitfield (R-Ky.), chairman of the Subcommittee on Energy and Power opened the hearing citing a NERA (National Economic Research Associates—an economic consulting firm) study that “put the total cost at $366 billion through 2031 and estimates increases in electricity prices of 12% or more.”

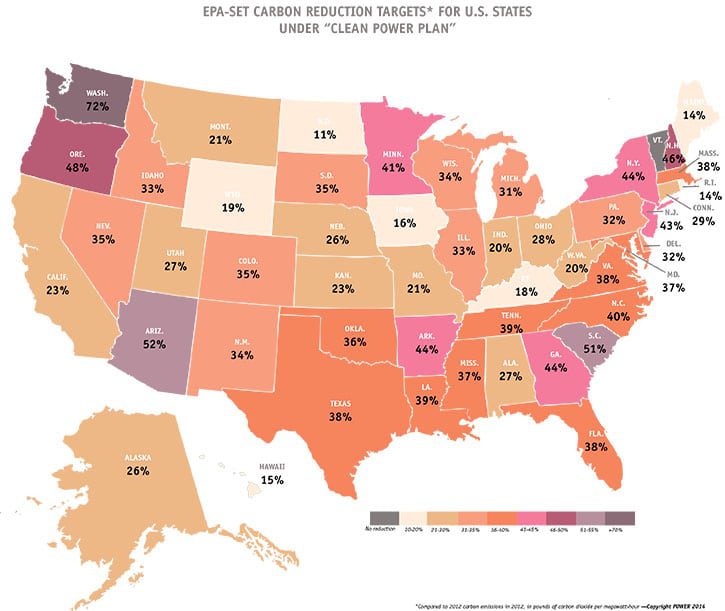

For Florida to achieve its designated 38% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions, average electric bills in the state would need to increase between 13% and 17% by 2030, said Florida Public Service Commission Chairman Art Graham. He also noted that the Florida Electric Power Coordinating Group Environmental Committee, which represents a number of utilities on environmental issues, had made clear that “existing electric system investments are not sufficient to comply with the Clean Power Plan regardless of how those resources are used.” Average utility rate increases may approach 25% to 50%, depending on size and generating mix reflected in current rates, the group said.

The Florida Office of Public Counsel, meanwhile, conservatively estimated that state efforts for building blocks 1, 3, and 4 could cost $1.15 billion, $16.8 billion, and $8.6 billion respectively, Graham said.

Participating in a regional cooperative is one proposed regional compliance mechanism that could allow states to pool staff resources and state budgets, and allow states to “achieve a lot more, for a lot less,” Commissioner Kelly Speakes-Backman of the Maryland Public Service Commission and chair of the nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) testified. Carbon pollution in the RGGI region has decreased by more than 40%, she said. While she did not provide cost estimates, she said that as a part of RGGI, Maryland has seen benefits, including that its low-carbon generation share has increased from 36% to 55%, while coal’s share has dropped from 54% to 44%.

In Ohio, on the other hand, where utilities, such as American Electric Power, FirstEnergy, and Duke Energy, have already decided to retire nearly 5 GW of coal-fired capacity, costs are expected to soar, said Craig Butler, director of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency. The Public Utilities of Ohio forecasts that wholesale market energy prices will be 39% higher in 2025, costing Ohioans about $2.5 billion—a figure that doesn’t include other significant costs such as increases in capacity pricing and significant investments in upgrading the transmission system, he said.

Legal Issues: The Little-Known Codicil That Could

More uncertain than costs, meanwhile, is the proposal’s legality, most witnesses testified.

The committee’s Republican leaders underscored the dispute involving the EPA’s authority. “[T]his proposed rule yanks the rug out from under states, with EPA dictating to states and effectively micromanaging intrastate electricity policy decisions to a degree even the agency admits is unprecedented. This raises a broad array of legal issues, not to mention that it is bad policy,” said Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Rep. Fred Upton (R-Mich.).

One witness—Harvard Law School professor of constitutional law Laurence H. Tribe—noted that states that did not comply with the 2016 deadline to develop the EPA-approved laws could face sanctions, “including the potential loss of federal highway funds, and the takeover of their energy sectors by an inflexible federal plan of uncertain scope that would inflict significant economic damage.” But, he said, the EPA lacks the statutory and constitutional authority to adopt its plan.

Tribe, who disclosed that he was retained by Peabody Corp. to provide his independent analysis of the EPA’s proposals, explained that the EPA relies on Section 111 of the Clean Air Act (CAA)—a provision about regulating “new sources” of emissions, not “existing sources,” he said.

“My study of the Clean Air Act convinces me, and would convince a reviewing court, that, because the source categories EPA seeks to regulate—coal-fired power plants—are already regulated under Section 112, the express statutory prohibition in Section 111(d) flatly bars EPA’s Clean Power Plan, making that plan, quite literally, a ‘power grab,'” Tribe testified.

“If ever there were an elephant in a mouse hole, the EPA’s plan is it—and it’s an unconstitutional elephant to boot,” Tribe said.

Tribe’s testimony was echoed by Allison Wood, a partner at law firm Hunton & Williams LLP. Wood noted that among the proposal’s “legal deficiencies … that will certainly be litigated” is its attempt to redefine the statutory term “system of emission reduction.” The proposal relies on a “dramatic redefinition of the word ‘system’ to broaden the program beyond the source by claiming that it may base a standard of performance on any ‘set of things’ that leads to reduced emissions from the source category overall.” This is misguided, she said. “A ‘system of emission reduction’ must begin and end at the source itself.”

In contrast, Richard Revesz, a professor of law at the New York University School of Law who served on the EPA’s Science Advisory Board, told lawmakers that the Clean Power Plan is well-justified under the Clean Air Act and the Constitution, and is consistent with regulatory practice under the administrations of both political parties. The EPA’s authority under Section 111(d) was also sound, he said.

“In other words, if EPA has already used Section 112 to regulate emissions of Pollutant A from Source Category X, it cannot also regulate emissions of Pollutant A under Section 111(d). It can, however, use Section 111(d) to regulate emissions of some other pollutant from Source Category X,” Revesz said. He also noted that Section 111(d) does not limit standards of performance to technological, end-to-pipe requirements, pointing out that Congress “specifically removed a requirement that performance standards be technologically based in its 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act.”

Certain Litigation with an Uncertain Outcome

Some lawmakers’ questions dwelled on concerns that the rule is complex—it will require a “complete overhaul” of each state’s energy portfolio—and that the deadline for state plans is looming. The EPA has said it will finalize the rule this summer, and states will then have a year, until the summer of 2016, to finalize state plans. The compliance period for the rule has been postponed to begin in summer 2020 (instead of on Jan. 1, 2020).

Other lawmakers, however, pressed witnesses to comment on what could happen if states and regulated entities were forced to comply with the rule before courts decide legal challenges.

Wood, who has represented power sector members before landmark Supreme Court cases involving climate change—including Massachusetts v. EPA—said that litigation will certainly occur, but its outcome is uncertain. Unless the rule is stayed by the court during litigation—”which is highly unusual and cannot be counted on,” she said—efforts to comply with the rule will have to proceed.

“Because of the complexity of the rule and the enormous ramifications it has for how energy is distributed in each state, the ability to wait and see what happens in court is not a realistic option,” Wood said. Yet, “If the rule is ultimately held to be unlawful, the states will have already expended enormous amounts of resources to develop the plan, and any laws or regulations that have been enacted cannot be easily reversed,” she said.

The legal uncertainty has also left power generators in a fog, Wood pointed out. Generating companies had stalled decisions to make improvements or install emission control equipment on certain power plants because it is uncertain whether those plants will remain operational after the rule goes into effect.

“Companies are also reluctant to enter into long-term contracts for power or fuel during the pendency of the rulemaking and the state planning process, which can add costs that are being passed on to consumers. If companies are going to need to increase their renewable generation in order to meet customer demand, then decisions need to be made now regarding the timing of that construction. Decisions will need to be made about plant closures, and once these decisions have been made, they are not easily reversed,” she told lawmakers.

—Sonal Patel, associate editor (@POWERmagazine, @sonalcpatel)