TransAlta Corp., a large, multinational investor-owned electric generating company sitting in the middle of Canada’s fossil fuel riches in Alberta, is offering to move away from coal. What’s behind the Calgary company’s “Dial down coal. Dial up renewables” strategy?

When it comes to a transition away from coal, TransAlta Corp. is playing political defense.

The Canadian province of Alberta contains among the richest fossil energy resources in the world, including oil (and oil sands), natural gas, and coal. For decades, Calgary-based TransAlta Corp. was a conventional utility, founded on hydropower and grounded in coal. In the 1990s, when the province deregulated its electricity market, the company became a generating company selling power through power purchase agreements with distribution utilities and into the Alberta wholesale market.

In recent decades, TransAlta has relied on coal as its primary fuel. Then last October, TransAlta made a bold proposal to the province’s Climate Change Advisory Panel, which it called “Dial Down Coal. Dial Up Renewables.” The company said it is willing to “dial down” coal-fired generation by 20%, starting in 2016 and put a hard cap on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. At the same time, the company said it is prepared to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in new renewables, including wind, solar, and hydro.

Don Wharton, TransAlta’s managing director of coal transition, acknowledged that the company’s proposal is reactive. “It’s a defense against a preemptive closure of coal units,” he told POWER. “We are taking our cues from the statement of intent of the government, and our proposal does that.” Wharton said, “It’s not like we are fighting against the government, but we are looking for a sensible approach.”

In a November op-ed in the Calgary Herald, TransAlta CEO Dawn Farrell said, “So we extend an open invitation—which I first offered at the Pembina Climate Change Summit in Edmonton last September—to environmental groups, our employees, communities and the province to sit down and reach an agreement that shows the world what Alberta can do.”

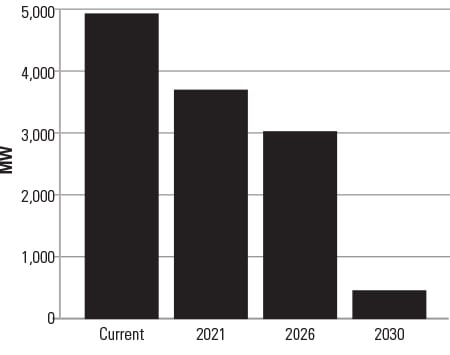

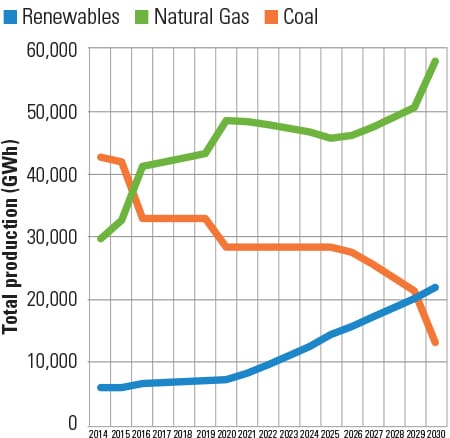

TransAlta’s generation transition plan is a “let’s-make-a-deal” offer to the Alberta government, which is advancing a GHG plan that could rule out coal generation by 2030 (see sidebar “Alberta’s GHG Plan”). The company is offering a less-extreme approach with its proposal to cut back on coal generation (Figure 1), cap its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, and go forward with ambitious renewable generation (Figure 2), including 350 MW to 400 MW of new hydro on the North Saskatchewan River.

|

|

1. TransAlta’s policy proposal imposes a hard cap on coal-fired power. Source: TransAlta |

|

|

2. TransAlta’s plan for fuel changes. Source: TransAlta |

Alberta’s GHG PlanAlberta Premier Rachel Notley’s platform to reduce greenhouse gases (GHGs) from Alberta’s energy economy, unveiled (with many details missing) late last November (http://bit.ly/1MLifPz), focuses on electric power generation. The plan would phase out “all pollution created by burning coal” by 2030 with a move to gas and renewables through a hybrid carbon tax and cap-and-trade regime. Renewables, mostly wind, would replace “two-thirds of coal-generated electricity,” with gas providing baseload capacity. Renewables would constitute “up to” 30% of the province’s “electricity production,” which presumably means energy rather than capacity, by 2030. The province’s plan would set a CO2 emissions cap for all fossil generation at 0.37 ton/MWh, which combined cycle gas plants can achieve today. Generation above that would have to pay C$30/ton for the shortfall; generation that can come in under the limit would have emissions to sell. According to TransAlta’s Don Wharton, coal cannot achieve that emissions standard. Coal’s best CO2 emissions rate is 1 ton/MWh. (For more on low-carbon technology options for coal-fired generation, see “CHP and Other Technologies Could Breathe New Life into U.S. Coal-Fired Power Plants” in this issue.) The Notley plan claims it would maintain reliability, offer price stability, and ensure “that capital is not unnecessarily stranded.” The Notley approach relies on a carbon tax, starting at $20/ton in 2017, rising to $30/ton in 2018, and increasing at inflation plus 2% thereafter. The Notley plan also claims that it would be “revenue neutral” and that “one-hundred percent of the proceeds from carbon pricing will be reinvested in Alberta.” That claim of revenue neutrality has drawn some skepticism. In a detailed, and generally favorable, analysis of the Notley plan in the Canadian magazine Maclean’s, economist Trevor Tombe at the University of Calgary argues that revenue neutrality means that every dollar from the carbon tax means a reduction in an existing tax. Under that definition, he says, “The Alberta carbon tax plan is not revenue neutral—not at all.” He says that nothing in the Notley panel outlining the greenhouse plan “suggests any existing tax will be lowered.” |

TransAlta’s move came in the context of a provincial election last May that overturned a 44-year run of governance by the business-oriented Progressive Conservative Party. The election elevated the liberal and environment-oriented New Democratic Party and its leader, Rachel Notley, into power. Notley campaigned on environmental issues, which played well at the time.

Soon after her election, Premier Notley called for cuts in CO2 emissions from the province’s coal-fired generation by 2030 that look to TransAlta and others as unachievable. The Notley policy would phase out coal-fired CO2 emissions by 2030, cap GHG emissions from oil sands operations, and impose an escalating carbon tax. Notley appointed a five-member Alberta Climate Leadership Panel, headed by University of Alberta energy economist Andrew Leach, to come up with the details for her pronouncement, which was unveiled in November.

TransAlta CEO Farrell, in September remarks to the Pembina Institute (an Alberta environmental think tank), made clear that the company is angling for a compromise with the government. “My case is simple,” she said. “It’s the case for a collaborative process to accelerate and achieve mutual objectives. We believe it will result in good environmental and economic policy, including job protection—something that is needed particularly now that we must create jobs and economic prosperity while also taking care of the environment.” Alberta’s fossil energy–based economy has been hurting as a result of plummeting oil prices.

TransAlta announced its dial-down coal plan in anticipation of Notley’s shutdown decree. Notley’s approach became part of the Canadian GHG reduction promises delivered to the United Nations climate meeting in Paris in early December. (See “THE BIG PICTURE: GHG Reduction Pledges” in this issue.) At a press conference in her home city of Edmonton, Notley said, “Our goal is to become one of the world’s most progressive and forward-looking energy producers.”

How Notley’s overall plan and the details of the offer from TransAlta will mesh is not yet clear. TransAlta’s Wharton said it will take six months or more of negotiations among the provincial government, the Alberta market operator, and provincial energy producers, including TransAlta, before a final deal can be done.

The Financial Market’s View

The results could be costly to the generating company. A TransAlta submission to Alberta’s Climate Change Advisory Panel in October said the company’s plan could cost its customers C$75 billion by 2030, compared to the government’s plan, which could have impacts as high as $103 billion. The Financial Post quoted an analysis from iA Securities analyst Jeremy Rosenfield that the Notley policy could leave TransAlta with C$1 billion in stranded assets.

A billion-dollar hit would be hard for TransAlta to take. The company has about C$3 billion in annual revenues on an asset base of about C$9 billion.

TransAlta has been experiencing financial problems for some time. Last year, it trimmed 486 positions, 239 from its Calgary headquarters and 247 from coal generation and mining operations, in a cost-cutting move. That’s out of about 1,300 employees (and thousands of others who depend on the company’s business). On September 30, Moody’s Investors Service announced it was reviewing TransAlta’s debt rating, with the likelihood of a downgrade to below investment grade. Moody’s senior analyst Gavin MacFarlane said, “TransAlta continues to generate weak financial metrics for an investment-grade rating. Management has been implementing its strategy to delever TransAlta; however, it increasingly looks like too little, too late.” TransAlta holds C$4.2 billion in debt.

At the same time as the Moody’s announcement, TransAlta agreed to pay C$56 million to settle a dispute with the province’s Market Surveillance Administrator for alleged market manipulations in 2010 and 2011. While TransAlta insists it followed the market rules, the market monitor found that the company had shut down power plants during peak demand periods in order to push up power prices.

The Canadian genco may also be a takeover target. In late October, Bloomberg reported that TransAlta “has held talks with more than one potential suitor in the past several months, people familiar with the matter said.” Bloomberg quoted Patrick Kenny at National Bank Financial in Calgary as saying, “Fundamentals have changed here in Alberta and that creates an opportunity for a buyer who might take a more constructive view.” Bloomberg reported, “Private-equity investors could be drawn to TransAlta’s high cash flow, relative to its beaten down share price, Kenny said. The company’s free cash flow yield is now about 20 percent, he said.”

Generation Then and Now

TransAlta began in 1911 with construction of the 14-MW Horseshoe Falls run-of-river hydro project, which is still in service. When power began flowing from the project, the Calgary Power Co. was born. The company’s first fossil-fueled plant, in the 1920s, was a small generator powered by coal gas, a 19th-century fuel. The company remained dependent on hydro for several decades (Figure 3).

That changed in 1956, when the company built its first coal-fired plant at Wabamun, west of Edmonton and adjacent to a coal reserve of more than 50 million tons. That’s where the three major coal-fired stations, including the 2,141-MW Sundance project, are located today. By 1968, Calgary Power was adding a fourth unit at its original Wabamun plant and had started construction on the Sundance plant. In 1970, the utility commissioned the first 286-MW Sundance unit. Five more units went online through 1980.

Calgary Power renamed itself TransAlta in 1981. The next year, the company relocated the rural village of Keephills away from its coal mining operations in the area and commissioned the Keephills generating plant in 1983. The end of the 20th century saw the rise of competitive wholesale markets in the province and TransAlta’s expansion outside of Canada, successfully bidding for the Centralia plant and mine in the U.S. With market deregulation, TransAlta sold off its distribution business, becoming a pure generating company.

According to its website, TransAlta has ownership, either in full or part, of five coal-fired plants in Canada, all in Alberta, and all mine-mouth operations (see sidebar “TransAlta’s Coal Holdings”). TransAlta’s share amounts to 3,591 MW. The company also owns the Highvale Mine, a strip mine that supplies the three TransAlta generating stations west of Edmonton. It is the largest surface coal mine in Canada, producing about 13 million metric tons of low-sulfur coal annually.

In addition to its heavy presence in coal, TransAlta also has significant gas generation, with shares or full ownership of six gas-fired plants in Canada (including three in Ontario) and three in Australia, according to the company’s website. The majority of the gas-fired Canadian plants are cogeneration units, with sales of power and process steam.

Hydro, the company’s first generating resource, now amounts to 936 MW at 27 units from coast to coast. The company has also gone in big for wind in recent years. TransAlta claims it is the country’s largest wind generator, with nameplate capacity of 1,522 MW, or 15.6% of the company’s generating capacity. Having made its first wind power acquisition in the 1990s, the company expanded its wind portfolio at the turn of the century, along with ventures into geothermal.

In 2008, TransAlta announced a plan to develop a C$1.9 billion carbon capture and storage project at the Keephills 3 plant, “Project Pioneer,” with C$1.2 billion from the provincial and federal governments. Capital Power and Enbridge were partners. After considerable analysis, TransAlta killed the project in 2012 as fundamentally uneconomic.

Uncertain Future

Today, TransAlta faces its toughest challenge. Negotiations among the parties involved in the Notley GHG plan are likely to persist well into next year. According to TransAlta’s Wharton, “The government has given lots of consideration to our proposal. The reaction to date is that they are more interested in using economic instruments, such as a carbon tax, with a regulatory framework around that. In our view, that would produce fewer greenhouse gas reductions at higher costs.”

Provincial politics could also impinge on the negotiations, as the Alberta economy faces a long-term slowdown driven by world oil economics. As oil prices decline and the province faces difficulties with its oil-based economy, the Notley plan and TransAlta’s counter will both increase electricity prices. Wharton said, “Our customers and the communities where we both serve and have operations are extremely concerned.”

— Kennedy Maize is a long-time energy journalist and frequent contributor to POWER.