The first operational rules finalized by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for routine commercial use of drones could have major implications for utilities and power companies, which are increasingly using them for operations and maintenance.

The new rules (Part 107 of the Federal Aviation Regulations) that apply to unmanned aircraft systems (UAS)—or drones—weighing less than 55 pounds and used for non-hobbyist operations will take effect in late August.

They limit drone operations to 400 feet above ground or above a structure, and at a maximum speed of 100 miles per hour (87 knots). They also require operators to fly drones only in daylight and twilight (but only if the drone has anti-collision lights), and to always keep drones within unaided sight, specifically, to avoid manned aircraft. The rules also prohibit operators from flying a small UAS over anyone not participating in the operation or under a covered structure.

The rules specify that drones can carry external loads if they are securely attached and do not affect flight control, and they allow property transportation, provided the drone’s systems, payload, and cargo altogether weigh less than 55 pounds.

Significantly, the rules also require that commercial drone operators hold a remote airman certificate with a small-UAS rating (or be under supervision of person who holds the certificate). That certificate can be obtained either by passing an initial aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center or, if the operator holds a Part 61 pilot certificate, he or she must complete a flight review and take a small-UAS online training course provided by the FAA.

Operators are also responsible for ensuring a drone is safe to fly.

The UAS must also be registered. Under the rules, the FAA may ask to inspect or test a drone. Operators must maintain and provide any associated records pertaining to the UAS to the FAA on request.

Complications on the Horizon

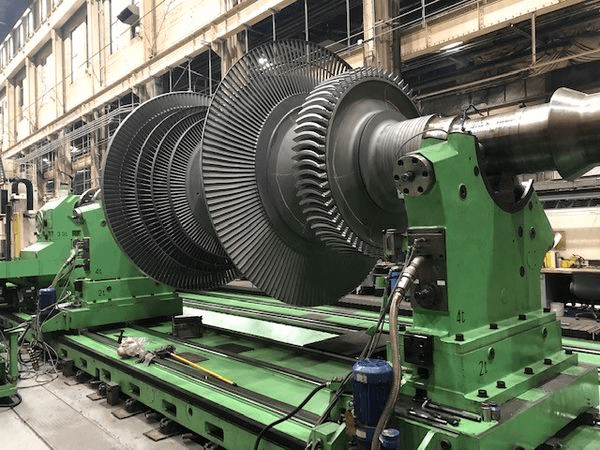

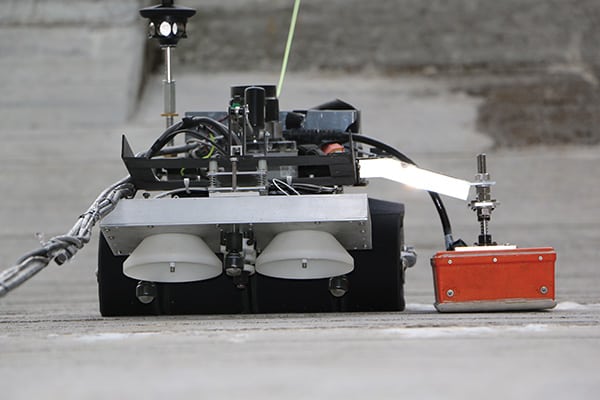

The use of drones in the power sector has kicked up significantly, owing to advantages that promote worker and plant safety. Drones are also being used to reduce inspection costs, assess and extend the life of components and power plants, and enable nondestructive inspections of areas that are otherwise difficult to access.

But before the new rule was finalized, limitations governing commercial drone use were in flux. The industry most conspicuously sought permission from the FAA to fly drones in U.S. airspace, even if just for demonstration, through an exemption under Section 333 of the FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012.

When enacted, that law directed the secretary of transportation to determine whether UAS operations could safely be conducted in U.S. airspace and, if so, to establish rules for their safe operations.

The FAA’s final rule, which adds a new part (Part 107) to the Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations in accordance with Section 333, evolved from comments submitted in response to the agency’s February 2015–issued notice that it was mulling the adoption of rules for the operation of small UAS in the national airspace system. The framework in the new rule is also designed to accommodate technologies as they evolve and mature, the FAA said.

According to the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), since 2014, FAA authorizations for low-risk, controlled missions in U.S. airspace through the Section 333 exemption have soared. As of September 2015, the federal agency had approved about 1,550 applications for the exemption, including more than 80 for utilities and drone vendors for power-related uses. EPRI says that hundreds of additional utility and vendor requests are under review.

An FAA spokesman told POWER on June 22 that the agency is contacting every company and individual that received a Section 333 exemption grant or has an exemption petition pending. The letter explains that existing Section 333 exemption holders can choose to continue to operate in accordance with their exemption or to operate in accordance with the new Part 107, once it takes effect.

However, many pending applicants may need to apply for a waiver under the new rules. “In such cases, the FAA would notify the applicant and automatically convert the 333 application to a 107 waiver application unless the applicant affirmatively elects to remain under the previous consideration,” Michael Sievers, co-chair of the unmanned aircraft systems practice at law firm Hunton & Williams LLP, told POWER on June 22.

How the New FAA Rules Affect Power Sector Drones

But while the new FAA rules finalized on June 22 offer clarity, they aren’t perfect.

Although the rules apply to a broad range of commercial applications, a few provisions are of specific importance to the energy sector, Sievers said.

“A prime example is the manner in which the maximum altitude restriction is formulated,” he said. If the small UAS is operated within a 400-foot radius of a structure it may be flown higher than 400 feet above ground level so long as it remains below 400 feet above the structure’s immediate uppermost limit.

“This formulation should provide significant leeway in conducting inspections of towers and other energy infrastructure components,” he explained.

For the power industry, the rule is just a first step, however. “More work remains to be done to enjoy the full benefits of UAS, especially enabling the safe operation of unmanned aircraft beyond visual line of sight,” said Tom Kuhn, president of the Edison Electric Institute (EEI) in a June 21 statement.

The ability to operate a UAS beyond the visual line of sight of an aircraft pilot is a key component to efficient use of UAS for certain utilities or power companies, noted Sievers.

“While Part 107 does specifically enumerate the visual line of sight restriction as one of the operating conditions that is subject to waiver, the manner in which the waiver process will be implemented is not well known at this time,” he added.

It is also uncertain whether waivers will be reviewed and granted on an expedited basis, or in a general manner in advance, in the case of storm recovery efforts, Sievers said.

For now, the EEI—the lobbying group representing investor-owned utilities—has said it will continue to work with the FAA to “demonstrate safe UAS usage and to develop guidelines that will allow companies to improve routine maintenance of our energy infrastructure and to help restore service to our customers more quickly following natural disasters.”

For an in-depth look at how drones are being used for power plant operations and maintenance, see our April 2016 cover story, “ Leveraging Drones and Robots for O&M Savings.”

—Sonal Patel, associate editor (@POWERmagazine, @sonalcpatel)